*/

Karlia Lykourgou puts forward an argument for chambers funded egg-freezing loans

Fertility is increasingly being identified as a key issue relevant to equality in the workforce. Corporate firms such as Meta, Google, Amazon, eBay and Reddit offer its female employees financial assistance with egg-freezing and IVF. Law firms such as Osbourne Clarke and Cooley are similarly involved, with the latter offering its employees up to £45,000 towards treatments (‘From subsidised egg freezing to unlimited IVF leave, to retain the best talent London’s biggest companies are going the extra mile on fertility, says Claire Cohen’, Evening Standard, 3 November 2023).

The media have reported on this issue extensively, with a new podcast In/Fertility in the City recently highlighting the impact of fertility on the legal sector (‘Why law firms must start using the F word’, Legal Futures, 30 May 2023). This suggests chambers should also be turning their minds to this.

For years the number of women at the Bar has been declining. The time has come to consider some new, practical steps to reverse the trend. One idea would be to follow the example of law firms, and for chambers to offer small loans for egg-freezing treatments.

The Bar Council’s 2014/15 report on women at the self-employed Bar noted the high number of women leaving the Bar after becoming parents (Snapshot: The Experience of Self-Employed Women at the Bar, Bar Council, June 2015).

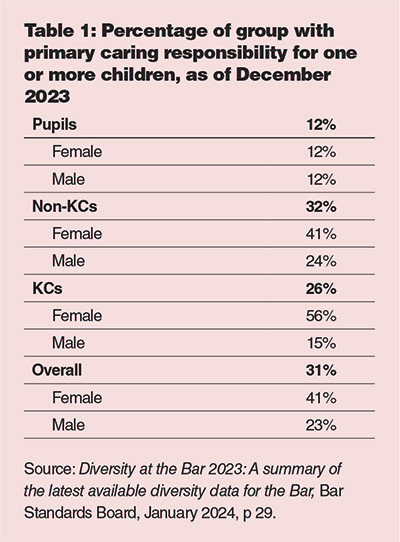

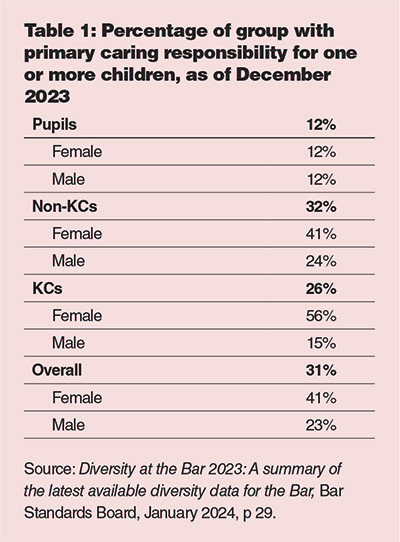

This is supported by the most recent Bar Standards report on diversity at the Bar which provided statistics for barristers with primary caring responsibility for one or more children as of December 2023 (see Table 1).

This shows that women at the Bar seem to be starting off with the same amount of responsibility as their male counterparts but then as their careers develop, more of them take on primary caring responsibilities for children.

The Bar Council reports that out of the figures for barristers who started their practice in the early 1990s, around 35% of women left the Bar before year 15 compared to 24% of male barristers (Key trends shaping recruitment and retention at the Bar, Bar Council, October 2022). This rate of attrition seems to be significant around year five of practice.

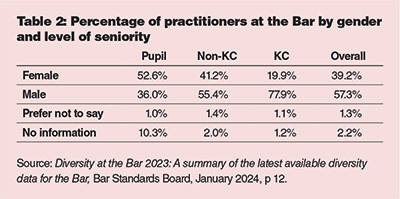

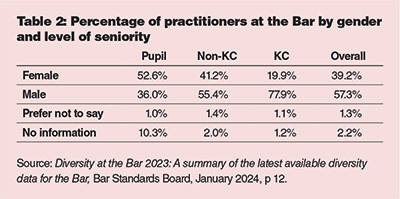

This decline in numbers of women at the Bar over time reflects figures showing the low number of women who are reaching the highest levels of the profession. As of 2023, just 19.9% of silks (see Table 2) and only 37% of all court judges were women (Diversity of the judiciary: Legal professions, new appointments and current post-holders – 2023 statistics, September 2023).

This issue is particularly acute at the Criminal Bar where the nature of the job requires court attendance in person and factors such as warned lists, last minute evidence and travel make it difficult for women to run a practice and have a family either with or without a partner. For this reason, it is not unusual for women to have to surrender their criminal practice, take a significant sabbatical or change their practice to another, more paper-based area to have children. Most factors in this decision will depend on the woman’s financial circumstances and whether child-care can be shared with another.

Bar Council data shows the average age for a pupil has risen to 28.5 (Key trends shaping recruitment and retention at the Bar Report). Statistically women experience a decline in their fertility from the age of 30, with a sharper decline from the age of 35 (‘A guide to fertility: At what age does fertility begin to decrease?’, British Fertility Society).

The decline of fertility from the age of 30 means women are under great pressure to decide if they wish to start a family at a time when their careers are just under way.

Increasingly women in all professions are choosing to freeze their eggs to try and preserve their fertility in circumstances where they are unsure if they want a child later in life or the conditions for having a child are not right at that time (‘Dramatic rise’ in number of women freezing eggs in UK’, The Guardian, 20 June 2023).

Egg-freezing gives women more time to:

Egg-freezing is a procedure which involves stimulating a woman’s egg-production with hormones, then retrieving the eggs and freezing them so pregnancy can be attempted later through in vitro fertilization (IVF). It costs between £3,645 and £5,750 per cycle depending on the clinic and extras involved. Women typically undergo one to three cycles depending on the number of eggs retrieved. Most clinics will offer a discount on the subsequent cycles, making the average cost around £4-7,000. There is then a monthly cost of storage amounting to £300-400 per year with some clinics including the price of one year’s storage in their fee.

Egg-freezing is difficult to afford, particularly for anyone with a legal aid practice. It will also be especially challenging to save up for in the lean years of training and makes it hard to save up for anything else, such as a deposit on a house. This puts women at a disadvantage to their male colleagues who don’t have to find extra savings for this procedure or worry about balancing their career advancement against their biological clock.

In terms of the practicalities of this procedure: women inject themselves for two to three weeks with hormones to stimulate egg-growth and must attend around three scans during that time to see how the eggs are growing and to determine when to trigger the egg retrieval. They must then go in for the procedure where they are sedated and will usually require 24 hours to recover. If insufficient number of eggs have been retrieved, then she can repeat this medication and retrieval process again to collect more eggs.

The need to ensure the eggs are being monitored consistently means women must go to a specific clinic at certain intervals and cannot miss appointments. The drugs taken to induce egg growth can also cause abdominal discomfort, tiredness and grogginess. It is possible to work during this time, but can be harder to achieve optimum performance, particularly at acute times such as trial.

Therefore, during an egg-freezing cycle women will either have to ask the judge for time out of court or ideally book time out of their diaries to make sure they can get to their appointments and aren’t too affected by the hormones. This is likely to impact their earnings.

There are two clinics in London that offer loans for egg-freezing. One of these requires a 20% deposit and a 0% loan that must be paid back within 12 months or the rate increases to 9.99% for 24 to 36 months. The other offers a 0% loan with no extension on the 12-month period.

These funding schemes make egg-freezing more affordable to some, but they also restrict women to these two clinics, which is significant as an individual may prefer a different clinic due to the location, service, or price point on offer.

Paying the loan back in 12 months is also more difficult if the individual has had to return or refuse trials so she can undergo the egg-freezing procedure in the first place. It is also a steep additional monthly expense for anyone with a junior legal aid practice.

Women have the option of obtaining a traditional loan from a high-street bank, but not everyone will be eligible as a self-employed barrister and the rate of repayment will be much higher.

If chambers were willing to offer loans to its female members for egg-freezing then this could cover part or all of the cost, making it more affordable.

These repayments could be deducted from the member’s income in the same way chambers rent is deducted at source, either as an additional monthly payment or as an addition to rent in the same way Westlaw and Bar Mutual expenses are recovered.

As a guarantee for chambers, the member could be required to have enough aged debt in place to cover a certain amount of the loan and enough of a practice to demonstrate it could be paid back within a certain period e.g. three years.

Any chambers cost estimation would need to consider that the scheme is only likely to affect women aged between 25 and 40, not all women eligible would want to freeze their eggs, and not everyone who chooses to will apply for a loan at the same time.

In 2022/23 the number of female pupils at the Bar was 53.9%, up from 48.5% in 1999/00 (Diversity at the Bar 2022: A summary of the latest available diversity data for the Bar, Bar Standards Board, January 2023, p 11; Trends in retention and demographics at the Bar: 1990-2020, Bar Standards Board, July 2021, p 21). Progress has been made to improve diversity in the profession, but we need to consider some bigger, different ideas to help women stay.

Egg-freezing loans may not be feasible for all chambers, but they should still reflect on the business case for this idea. Failure to act means chambers will continue to lose women to secondment, more lucrative/employed roles, and desk-based areas of practice. This means chambers are less able to cover work, particularly in areas such as crime that require regular court attendance.

By investing in the wealth of talent they have identified, chambers can help themselves and improve the Bar as a whole by providing women with the option of delaying motherhood to a time when their careers are more established, and therefore easier to return to.

Fertility is increasingly being identified as a key issue relevant to equality in the workforce. Corporate firms such as Meta, Google, Amazon, eBay and Reddit offer its female employees financial assistance with egg-freezing and IVF. Law firms such as Osbourne Clarke and Cooley are similarly involved, with the latter offering its employees up to £45,000 towards treatments (‘From subsidised egg freezing to unlimited IVF leave, to retain the best talent London’s biggest companies are going the extra mile on fertility, says Claire Cohen’, Evening Standard, 3 November 2023).

The media have reported on this issue extensively, with a new podcast In/Fertility in the City recently highlighting the impact of fertility on the legal sector (‘Why law firms must start using the F word’, Legal Futures, 30 May 2023). This suggests chambers should also be turning their minds to this.

For years the number of women at the Bar has been declining. The time has come to consider some new, practical steps to reverse the trend. One idea would be to follow the example of law firms, and for chambers to offer small loans for egg-freezing treatments.

The Bar Council’s 2014/15 report on women at the self-employed Bar noted the high number of women leaving the Bar after becoming parents (Snapshot: The Experience of Self-Employed Women at the Bar, Bar Council, June 2015).

This is supported by the most recent Bar Standards report on diversity at the Bar which provided statistics for barristers with primary caring responsibility for one or more children as of December 2023 (see Table 1).

This shows that women at the Bar seem to be starting off with the same amount of responsibility as their male counterparts but then as their careers develop, more of them take on primary caring responsibilities for children.

The Bar Council reports that out of the figures for barristers who started their practice in the early 1990s, around 35% of women left the Bar before year 15 compared to 24% of male barristers (Key trends shaping recruitment and retention at the Bar, Bar Council, October 2022). This rate of attrition seems to be significant around year five of practice.

This decline in numbers of women at the Bar over time reflects figures showing the low number of women who are reaching the highest levels of the profession. As of 2023, just 19.9% of silks (see Table 2) and only 37% of all court judges were women (Diversity of the judiciary: Legal professions, new appointments and current post-holders – 2023 statistics, September 2023).

This issue is particularly acute at the Criminal Bar where the nature of the job requires court attendance in person and factors such as warned lists, last minute evidence and travel make it difficult for women to run a practice and have a family either with or without a partner. For this reason, it is not unusual for women to have to surrender their criminal practice, take a significant sabbatical or change their practice to another, more paper-based area to have children. Most factors in this decision will depend on the woman’s financial circumstances and whether child-care can be shared with another.

Bar Council data shows the average age for a pupil has risen to 28.5 (Key trends shaping recruitment and retention at the Bar Report). Statistically women experience a decline in their fertility from the age of 30, with a sharper decline from the age of 35 (‘A guide to fertility: At what age does fertility begin to decrease?’, British Fertility Society).

The decline of fertility from the age of 30 means women are under great pressure to decide if they wish to start a family at a time when their careers are just under way.

Increasingly women in all professions are choosing to freeze their eggs to try and preserve their fertility in circumstances where they are unsure if they want a child later in life or the conditions for having a child are not right at that time (‘Dramatic rise’ in number of women freezing eggs in UK’, The Guardian, 20 June 2023).

Egg-freezing gives women more time to:

Egg-freezing is a procedure which involves stimulating a woman’s egg-production with hormones, then retrieving the eggs and freezing them so pregnancy can be attempted later through in vitro fertilization (IVF). It costs between £3,645 and £5,750 per cycle depending on the clinic and extras involved. Women typically undergo one to three cycles depending on the number of eggs retrieved. Most clinics will offer a discount on the subsequent cycles, making the average cost around £4-7,000. There is then a monthly cost of storage amounting to £300-400 per year with some clinics including the price of one year’s storage in their fee.

Egg-freezing is difficult to afford, particularly for anyone with a legal aid practice. It will also be especially challenging to save up for in the lean years of training and makes it hard to save up for anything else, such as a deposit on a house. This puts women at a disadvantage to their male colleagues who don’t have to find extra savings for this procedure or worry about balancing their career advancement against their biological clock.

In terms of the practicalities of this procedure: women inject themselves for two to three weeks with hormones to stimulate egg-growth and must attend around three scans during that time to see how the eggs are growing and to determine when to trigger the egg retrieval. They must then go in for the procedure where they are sedated and will usually require 24 hours to recover. If insufficient number of eggs have been retrieved, then she can repeat this medication and retrieval process again to collect more eggs.

The need to ensure the eggs are being monitored consistently means women must go to a specific clinic at certain intervals and cannot miss appointments. The drugs taken to induce egg growth can also cause abdominal discomfort, tiredness and grogginess. It is possible to work during this time, but can be harder to achieve optimum performance, particularly at acute times such as trial.

Therefore, during an egg-freezing cycle women will either have to ask the judge for time out of court or ideally book time out of their diaries to make sure they can get to their appointments and aren’t too affected by the hormones. This is likely to impact their earnings.

There are two clinics in London that offer loans for egg-freezing. One of these requires a 20% deposit and a 0% loan that must be paid back within 12 months or the rate increases to 9.99% for 24 to 36 months. The other offers a 0% loan with no extension on the 12-month period.

These funding schemes make egg-freezing more affordable to some, but they also restrict women to these two clinics, which is significant as an individual may prefer a different clinic due to the location, service, or price point on offer.

Paying the loan back in 12 months is also more difficult if the individual has had to return or refuse trials so she can undergo the egg-freezing procedure in the first place. It is also a steep additional monthly expense for anyone with a junior legal aid practice.

Women have the option of obtaining a traditional loan from a high-street bank, but not everyone will be eligible as a self-employed barrister and the rate of repayment will be much higher.

If chambers were willing to offer loans to its female members for egg-freezing then this could cover part or all of the cost, making it more affordable.

These repayments could be deducted from the member’s income in the same way chambers rent is deducted at source, either as an additional monthly payment or as an addition to rent in the same way Westlaw and Bar Mutual expenses are recovered.

As a guarantee for chambers, the member could be required to have enough aged debt in place to cover a certain amount of the loan and enough of a practice to demonstrate it could be paid back within a certain period e.g. three years.

Any chambers cost estimation would need to consider that the scheme is only likely to affect women aged between 25 and 40, not all women eligible would want to freeze their eggs, and not everyone who chooses to will apply for a loan at the same time.

In 2022/23 the number of female pupils at the Bar was 53.9%, up from 48.5% in 1999/00 (Diversity at the Bar 2022: A summary of the latest available diversity data for the Bar, Bar Standards Board, January 2023, p 11; Trends in retention and demographics at the Bar: 1990-2020, Bar Standards Board, July 2021, p 21). Progress has been made to improve diversity in the profession, but we need to consider some bigger, different ideas to help women stay.

Egg-freezing loans may not be feasible for all chambers, but they should still reflect on the business case for this idea. Failure to act means chambers will continue to lose women to secondment, more lucrative/employed roles, and desk-based areas of practice. This means chambers are less able to cover work, particularly in areas such as crime that require regular court attendance.

By investing in the wealth of talent they have identified, chambers can help themselves and improve the Bar as a whole by providing women with the option of delaying motherhood to a time when their careers are more established, and therefore easier to return to.

Karlia Lykourgou puts forward an argument for chambers funded egg-freezing loans

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court