*/

Julian Norman surveys the debate generated by the government consultation on gender self-identification, the impact on women’s sex-based rights and why legal clarity will be crucial

As the government’s consultation over proposals to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (‘GRA’) closed, debate on and offline continues to rage – sometimes literally – over what exactly this will mean. Will reform of the GRA be purely a matter of simplifying an administrative burden, or will it inevitably have an effect on the Equality Act 2010 (EqA) and what it means, in law, to be male or female? Is this a zeitgeist-rattling sign of social progress, or a backwards step towards a philosophy that regards gender roles as innate?

At present, acquisition of a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) is open to transsexuals who have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria, who have lived in their acquired gender role for two years and who make a declaration that they intend to live in their acquired sex for the rest of their life. Once acquired, a GRC changes the person’s legal sex ‘for all purposes’.

The definition of transgender has expanded hugely since 2004. The term ‘transsexual’ used in Goodwin is no longer in currency, and it is understood that restricting a GRC to those who have what the ECtHR rather coyly described as ‘fully achieved’ transition, ie undergone surgery, is unlawful.

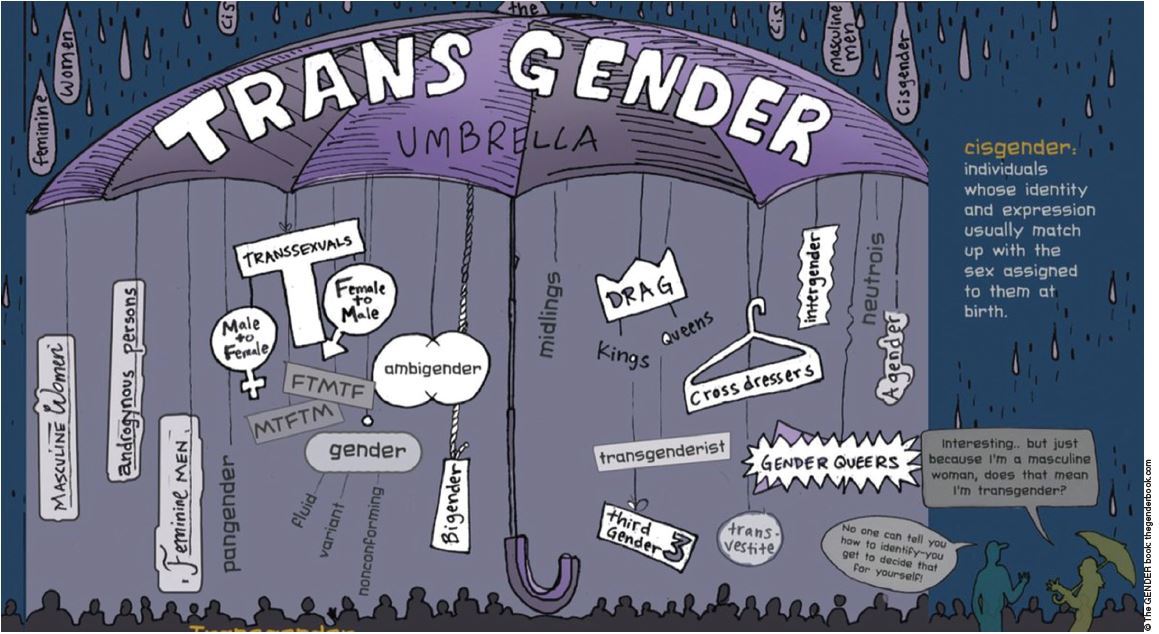

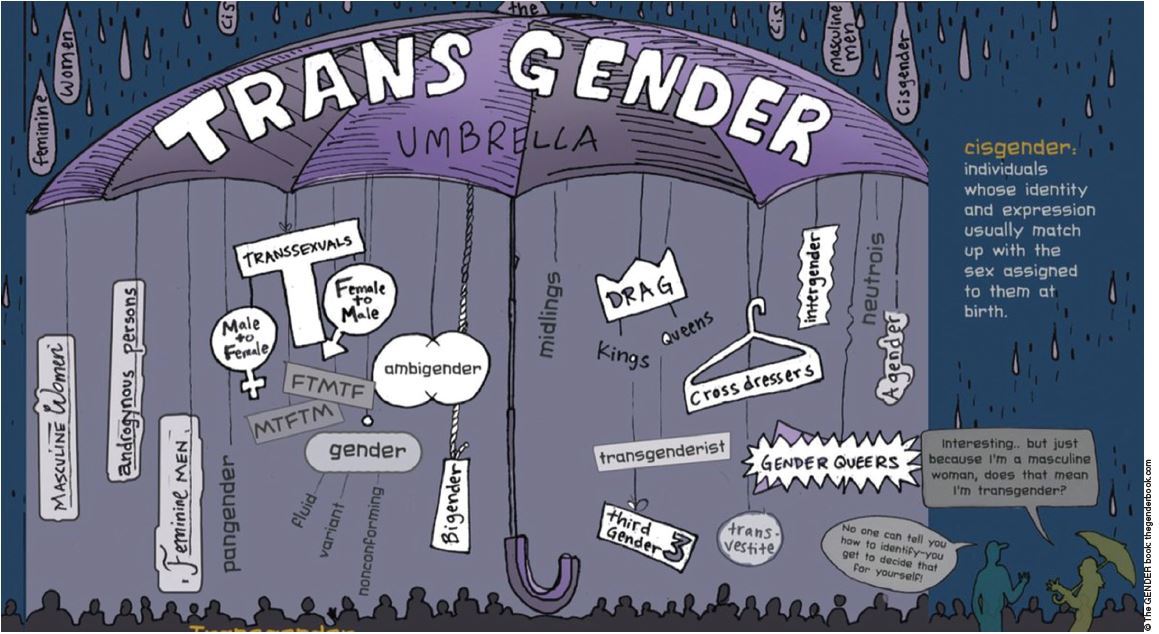

The modernised term now is transgender. Applying the Stonewall glossary definitions, this describes anybody whose innate sense of their own gender does not correlate to the culturally determined expressions associated with their sex at birth. In other words, anybody who does not feel affinity with the gender expectations attached to their sex can be understood as transgender. The illustration of the ‘trans umbrella’ below shows that transsexuals are now only a small number within the broader transgender movement. It is now quite legitimate for a person to define themselves as transgender, based on their self-perception, regardless of any intention to make physical changes.

The proposal is to replace the application and assessment process with a self-identification process, whereby a person may declare themselves a member of the opposite sex with a statutory declaration. The proposals upon which the government is consulting envisage that a GRC, and thereby the protected characteristic of sex, should be granted through simple statutory declaration. This opens up the legal status of ‘female’ sex to a vastly wider group than was contemplated by the original GRA, including to those who are not transsexual but may be cross dressers or gender fluid.

Some, particularly in the women’s sector, recognise that this will have a profound effect on the services they offer. The organisation Fair Play for Women has produced a document setting out the effect that even the current uncertainty over the scope of the exemptions has had on frontline service providers and service users in the women’s sector. Others have expressed disquiet that men who are not transgender might abuse the provisions of self-ID to gain access to single sex spaces protected by the EqA exemptions.

Claire McCann has recently argued in these pages that the proposed reforms would make little difference to the existing EqA exemptions, as there is no proposal to change the text of the EqA (‘Gender recognition and trans equality’, Counsel, August 2018). However, it is axiomatic that in changing the GRA application process, the EqA will itself be affected, because those considered ‘female’ within s 212(1) EqA must include those who acquire their sex through s 9(1) GRA. If the legal definition of female is widened to include anyone on the transgender spectrum who is willing to make a statutory declaration, and at the same time this spectrum is understood as encompassing everyone whose self-perception is at odds with the gender expectations attached to their sex, the purpose of the GRA, and the scope of the EqA exemptions, are changed.

Recent news items suggest that the women’s sector has cause to be worried. In Canada, where self-identification is law, the Vancouver Rape Crisis centre was pursued through the courts for supposedly excluding trans people, because the centre wished to maintain a single sex service. In Toronto, Christopher Hambrook accessed a women’s homeless shelter and attacked women by falsely identifying as a woman. Here in the UK, Karen White, a male rapist placed in HMP New Hall, sexually assaulted four women soon after being moved to the female estate. Only a week after White’s conviction, a paedophile serving an IPP sentence for grooming female teenagers was moved to HMPYOI Peterborough.

This is not gaudy sensationalism. Statistics obtained by Fair Play For Women, and confirmed by the government, show that about half of the 120 trans prisoners in British prisons are incarcerated for sex offences – vastly more, proportionally, than the male population. Neither I nor most other feminists believe that this suggests trans people are grossly more likely to be sex offenders than the rest of the population. The much more obvious answer is the one already given by prison psychologists: that those men who are violent, abusive and manipulative are willing to use any means, including a claim to transgender status, to further their own ends, whether that is to seek early release, to disassociate themselves from an offending past, or in rare cases to seek a pool of victims. That there are already laws against sexual assault is cold comfort to those who experience it. Frances Crook, CEO of the Howard League, has said: ‘It is a very toxic debate, but I think prisons have probably been influenced by some of the extreme conversations and have been bullied into making some decisions that have harmed women and put staff in an extremely difficult position.’

While such cases are rare, the eradication of single sex services (as Stonewall call for) is a wider concern. Where women are in prison, in refuge, or in shelters, female only space may be vital to their rehabilitation or recovery. No statistics can capture the discomfort of women in being expected to endorse a belief that woman is a perception and not a reality. We should be slow to legislate interference with single sex provision in such places, particularly where this will affect the funding of vital frontline services.

Finally, it is important to note that the LGBTQ+ community does not speak with one voice as to gender. Many people believe that they have an innate gender identity, fixed and immutable, and that a person is a man or a woman depending on that person’s self-perception rather than on their biological sex. Many others believe equally firmly that they do not have such an innate gender identity, pointing to the temporal and cultural variations in gender, indicating that social projections of gender are neither innate nor immutable. They regard dysphoria as a medical condition for which transition may be an acceptable treatment, but they do not believe that womanhood or manhood is dictated by innate gender or by self-perception. If gender is innate, then the cultural norms attached to the female sex (which have historically served to oppress women) are not a bug, but a design feature. A philosophy which seeks to ascribe women’s subjugation globally and historically to something innate within them has never ended well for women.

It is true that this debate has become toxic. Yet this is not an excuse for disregarding valid concerns. Whatever happens following the consultation, the government must be very clear about what effects are intended and how male and female are defined. The current situation lacks clarity, and it is crucial that the underlying laws which govern our society are coherent, workable, and easily understood.

Julian Norman is a barrister at Drystone Chambers. Her main practice is in immigration law with a particular interest in Article 8 HRA. She is a trustee of FiLiA, a women’s rights charity

As the government’s consultation over proposals to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (‘GRA’) closed, debate on and offline continues to rage – sometimes literally – over what exactly this will mean. Will reform of the GRA be purely a matter of simplifying an administrative burden, or will it inevitably have an effect on the Equality Act 2010 (EqA) and what it means, in law, to be male or female? Is this a zeitgeist-rattling sign of social progress, or a backwards step towards a philosophy that regards gender roles as innate?

At present, acquisition of a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) is open to transsexuals who have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria, who have lived in their acquired gender role for two years and who make a declaration that they intend to live in their acquired sex for the rest of their life. Once acquired, a GRC changes the person’s legal sex ‘for all purposes’.

The definition of transgender has expanded hugely since 2004. The term ‘transsexual’ used in Goodwin is no longer in currency, and it is understood that restricting a GRC to those who have what the ECtHR rather coyly described as ‘fully achieved’ transition, ie undergone surgery, is unlawful.

The modernised term now is transgender. Applying the Stonewall glossary definitions, this describes anybody whose innate sense of their own gender does not correlate to the culturally determined expressions associated with their sex at birth. In other words, anybody who does not feel affinity with the gender expectations attached to their sex can be understood as transgender. The illustration of the ‘trans umbrella’ below shows that transsexuals are now only a small number within the broader transgender movement. It is now quite legitimate for a person to define themselves as transgender, based on their self-perception, regardless of any intention to make physical changes.

The proposal is to replace the application and assessment process with a self-identification process, whereby a person may declare themselves a member of the opposite sex with a statutory declaration. The proposals upon which the government is consulting envisage that a GRC, and thereby the protected characteristic of sex, should be granted through simple statutory declaration. This opens up the legal status of ‘female’ sex to a vastly wider group than was contemplated by the original GRA, including to those who are not transsexual but may be cross dressers or gender fluid.

Some, particularly in the women’s sector, recognise that this will have a profound effect on the services they offer. The organisation Fair Play for Women has produced a document setting out the effect that even the current uncertainty over the scope of the exemptions has had on frontline service providers and service users in the women’s sector. Others have expressed disquiet that men who are not transgender might abuse the provisions of self-ID to gain access to single sex spaces protected by the EqA exemptions.

Claire McCann has recently argued in these pages that the proposed reforms would make little difference to the existing EqA exemptions, as there is no proposal to change the text of the EqA (‘Gender recognition and trans equality’, Counsel, August 2018). However, it is axiomatic that in changing the GRA application process, the EqA will itself be affected, because those considered ‘female’ within s 212(1) EqA must include those who acquire their sex through s 9(1) GRA. If the legal definition of female is widened to include anyone on the transgender spectrum who is willing to make a statutory declaration, and at the same time this spectrum is understood as encompassing everyone whose self-perception is at odds with the gender expectations attached to their sex, the purpose of the GRA, and the scope of the EqA exemptions, are changed.

Recent news items suggest that the women’s sector has cause to be worried. In Canada, where self-identification is law, the Vancouver Rape Crisis centre was pursued through the courts for supposedly excluding trans people, because the centre wished to maintain a single sex service. In Toronto, Christopher Hambrook accessed a women’s homeless shelter and attacked women by falsely identifying as a woman. Here in the UK, Karen White, a male rapist placed in HMP New Hall, sexually assaulted four women soon after being moved to the female estate. Only a week after White’s conviction, a paedophile serving an IPP sentence for grooming female teenagers was moved to HMPYOI Peterborough.

This is not gaudy sensationalism. Statistics obtained by Fair Play For Women, and confirmed by the government, show that about half of the 120 trans prisoners in British prisons are incarcerated for sex offences – vastly more, proportionally, than the male population. Neither I nor most other feminists believe that this suggests trans people are grossly more likely to be sex offenders than the rest of the population. The much more obvious answer is the one already given by prison psychologists: that those men who are violent, abusive and manipulative are willing to use any means, including a claim to transgender status, to further their own ends, whether that is to seek early release, to disassociate themselves from an offending past, or in rare cases to seek a pool of victims. That there are already laws against sexual assault is cold comfort to those who experience it. Frances Crook, CEO of the Howard League, has said: ‘It is a very toxic debate, but I think prisons have probably been influenced by some of the extreme conversations and have been bullied into making some decisions that have harmed women and put staff in an extremely difficult position.’

While such cases are rare, the eradication of single sex services (as Stonewall call for) is a wider concern. Where women are in prison, in refuge, or in shelters, female only space may be vital to their rehabilitation or recovery. No statistics can capture the discomfort of women in being expected to endorse a belief that woman is a perception and not a reality. We should be slow to legislate interference with single sex provision in such places, particularly where this will affect the funding of vital frontline services.

Finally, it is important to note that the LGBTQ+ community does not speak with one voice as to gender. Many people believe that they have an innate gender identity, fixed and immutable, and that a person is a man or a woman depending on that person’s self-perception rather than on their biological sex. Many others believe equally firmly that they do not have such an innate gender identity, pointing to the temporal and cultural variations in gender, indicating that social projections of gender are neither innate nor immutable. They regard dysphoria as a medical condition for which transition may be an acceptable treatment, but they do not believe that womanhood or manhood is dictated by innate gender or by self-perception. If gender is innate, then the cultural norms attached to the female sex (which have historically served to oppress women) are not a bug, but a design feature. A philosophy which seeks to ascribe women’s subjugation globally and historically to something innate within them has never ended well for women.

It is true that this debate has become toxic. Yet this is not an excuse for disregarding valid concerns. Whatever happens following the consultation, the government must be very clear about what effects are intended and how male and female are defined. The current situation lacks clarity, and it is crucial that the underlying laws which govern our society are coherent, workable, and easily understood.

Julian Norman is a barrister at Drystone Chambers. Her main practice is in immigration law with a particular interest in Article 8 HRA. She is a trustee of FiLiA, a women’s rights charity

Julian Norman surveys the debate generated by the government consultation on gender self-identification, the impact on women’s sex-based rights and why legal clarity will be crucial

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier