*/

After decades during which the UK’s main political parties have shamelessly weaponised criminal justice for electoral gain, the chickens have finally come home to roost. Successive governments have created new offences, raised sentences, reduced remission, increased tariffs and used inflammatory language that’s encouraged a full-throated media to pressure judges and the parole board – and always in one direction: heavier terms of imprisonment, and fewer releases. The result? An epic failure of public policy that has filled our crumbling prisons to capacity and forced a new Lord Chancellor, Shabana Mahmood, to announce emergency measures on remission, just to keep the system from collapse. But her immediate response buys just 18 months before the jails are full again. On its own, this looks very like the sticking plaster politics that the new Prime Minister decried so passionately in opposition.

This foreseeable crisis in prison capacity was well understood by the previous government. Alex Chalk KC, the estimable former Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, warned Rishi Sunak that remission would have to be increased just to keep our prisons functioning. But his pleas fell on deaf ears – and for entirely political reasons. Releasing prisoners early was bad electoral politics; let any crisis manifest itself after the election. Better to conceal it from the public, putting staff and inmates at risk, than to lose votes.

And this is how we got here. The cynical ramping up of expectations, and lurid portrayals of crime which was mainly falling, were political choices made by both parties in government, disconnected from the delivery of justice. But crucial, too, was the failure to increase prison capacity in the face of a rocketing prison population driven deliberately by public policy. Like operating a brewery without making any bottles, Labour and Conservative governments have been good at increasing the flow of inmates, but without creating any new spaces to house them. Frightening the public for political gain is one thing, refusing to spend public money to meet the consequences of your fearmongering is quite another.

In 2020, a government spending review promised an answer. An impressive 20,000 new prison cells would be created by 2025. Four years later, and just one year short of that date, we have no more than 5,000. It is now claimed that the full number will be operational in 2030. Does anyone believe this will happen? It is reported that one new prison building project has been delayed by the discovery of a badger set.

There are two reasons why building new prisons is not high on any government’s wish list. Firstly, their construction is horrendously expensive. Each newly created cell requires no less than £630,000 of capital expenditure. At this price, who would choose a prison over a well-equipped school, or a shiny new hospital?

The second reason is an even stronger deterrent: because for the great majority of prisoners on short sentences, those who are not dangerous, those who are addicts, mentally ill, or just a nuisance, prison demonstrably doesn’t work – and successive governments have possessed all the evidence to know this.

We don’t simply have the highest prison population in western Europe, we also have some of the worst recidivism rates when inmates are released. Twenty five per cent of adult prisoners go on to reoffend. For young offenders the figure is 30%. And for adults released from sentences of less than two years, no less than 50% reoffend.

Yet we know from reams of research that those committing similar offences who are put on community sentences outside prison have lower recidivism rates than their jailed counterparts. Why should this be surprising? As David Waddington, a notably right-wing Conservative Home Secretary said many years ago, ‘Prison is an expensive way of making bad people worse.’

Bereft of proper facilities for education or rehabilitation, strained to breaking point by austerity and neglect, ludicrously portrayed in some media outlets as ‘holiday camps’, and warehousing some of the most damaged individuals in our society, British prisons should be a stain on our collective conscience, and many of the Chief Inspector’s reports a source of national shame. What a tragic farce, then, that in so many cases they don’t even work. It is hardly a shock that many Republican states in the US, Texas included, are moving away from policies of mass incarceration, precisely because the policy is a wasteful use of tax dollars that fails to deliver on its most basic objective – public safety.

Can we learn the same lesson here? Well, perhaps. And an important tell may be the new Prime Minister’s appointment of James Timpson as Prisons Minister in the Ministry of Justice. Sir Keir Starmer is a careful man. At the Bar, he conducted his cases with notable skill and, more importantly, with great strategic sense, planning ahead to see off challenge. He knows very well that Lord Timpson is a formidable prison reformer who believes that only a third of those currently in prison truly belong there. Another third, he believes, should be receiving therapeutic mental health and addiction interventions in the community, and the rest on community sentences.

From what we know of Sir Keir’s attachment to planning and process, and we know quite a lot, it seems most unlikely that he would have brought Lord Timpson into his government if he didn’t intend to give his new prisons minister some space to create a new penal policy, less focused on incarceration and more directed towards punishment and rehabilitation in the community. It seems equally unlikely that Lord Timpson would have accepted this otherwise poisoned appointment in the absence of such assurances from the top.

So what might reform look like? Increased remission, for sure, perhaps as a permanent measure. And doubtless the resurrection of a Chalk proposal, a presumption that the most pointless and destructive sentences, those under 12 months, should be suspended – and even the wider application of this policy to all sentences under two years.

I also expect the government to cease bad faith attacks on judges and the Parole Board, to shift more resource to probation and rehabilitation, to propagandise the waste and destructive failure of prison as a solution to much offending, and to take full advantage of rapid developments in technology to make tagging a real alternative to remand and custody for many who would otherwise be locked up, usually in squalor.

This disaster is a shared responsibility, and it won’t do for the new government to try to blame everything on its immediate predecessor. The truth is that the last Labour government was equally culpable, crudely attacking judges and driving up tariffs, as well as introducing the disastrous sentence of imprisonment for public protection (IPP), and with no adequate prison building programme to house the inmates its policies were creating. If Labour doesn’t now understand and accept its own part in this debacle, it will hardly start from the right place in what must become a shared process of deep and broad reform, a complete change in the way we think about crime and punishment in our country.

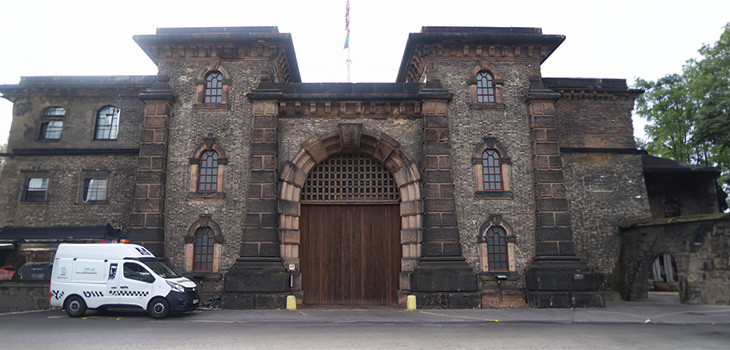

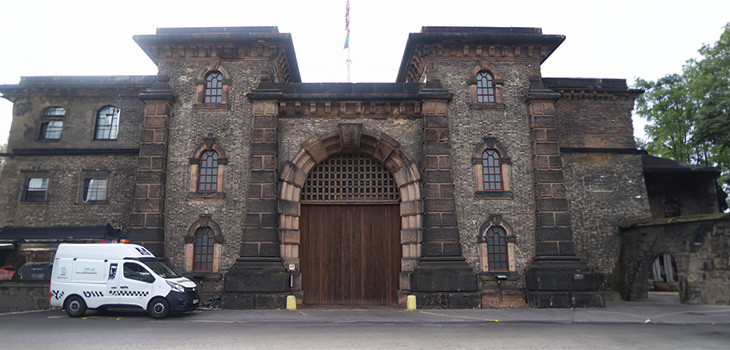

Prisons on the point of collapse: On 12 July 2024 the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Shabana Mahmood set out emergency plans to prevent the impending collapse of the criminal justice system – a temporary reduction of the proportion of certain custodial sentences served from 50-40% from September. Speaking at HMP Five Wells in Northamptonshire, the Lord Chancellor said: ‘Let me be clear, this is an emergency measure. This is not a permanent change. I am unapologetic in my belief that criminals must be punished.’

Penal reform ahead? An important tell may be the new Prime Minister’s appointment of James Timpson as Prisons Minister in the Ministry of Justice.

Co-presented by former DPP Ken Macdonald KC and Tim Owen KC, Double Jeopardy: The Law and Politics Podcast goes to the places where law and politics collide. Small boats, climate justice, transgender rights, Israel, and prisons under Labour, have brought Brenda Hale, Kathleen Stock, David Pannick, Alex Chalk, Melanie Phillips and many others to the conversation since 2022.

After decades during which the UK’s main political parties have shamelessly weaponised criminal justice for electoral gain, the chickens have finally come home to roost. Successive governments have created new offences, raised sentences, reduced remission, increased tariffs and used inflammatory language that’s encouraged a full-throated media to pressure judges and the parole board – and always in one direction: heavier terms of imprisonment, and fewer releases. The result? An epic failure of public policy that has filled our crumbling prisons to capacity and forced a new Lord Chancellor, Shabana Mahmood, to announce emergency measures on remission, just to keep the system from collapse. But her immediate response buys just 18 months before the jails are full again. On its own, this looks very like the sticking plaster politics that the new Prime Minister decried so passionately in opposition.

This foreseeable crisis in prison capacity was well understood by the previous government. Alex Chalk KC, the estimable former Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, warned Rishi Sunak that remission would have to be increased just to keep our prisons functioning. But his pleas fell on deaf ears – and for entirely political reasons. Releasing prisoners early was bad electoral politics; let any crisis manifest itself after the election. Better to conceal it from the public, putting staff and inmates at risk, than to lose votes.

And this is how we got here. The cynical ramping up of expectations, and lurid portrayals of crime which was mainly falling, were political choices made by both parties in government, disconnected from the delivery of justice. But crucial, too, was the failure to increase prison capacity in the face of a rocketing prison population driven deliberately by public policy. Like operating a brewery without making any bottles, Labour and Conservative governments have been good at increasing the flow of inmates, but without creating any new spaces to house them. Frightening the public for political gain is one thing, refusing to spend public money to meet the consequences of your fearmongering is quite another.

In 2020, a government spending review promised an answer. An impressive 20,000 new prison cells would be created by 2025. Four years later, and just one year short of that date, we have no more than 5,000. It is now claimed that the full number will be operational in 2030. Does anyone believe this will happen? It is reported that one new prison building project has been delayed by the discovery of a badger set.

There are two reasons why building new prisons is not high on any government’s wish list. Firstly, their construction is horrendously expensive. Each newly created cell requires no less than £630,000 of capital expenditure. At this price, who would choose a prison over a well-equipped school, or a shiny new hospital?

The second reason is an even stronger deterrent: because for the great majority of prisoners on short sentences, those who are not dangerous, those who are addicts, mentally ill, or just a nuisance, prison demonstrably doesn’t work – and successive governments have possessed all the evidence to know this.

We don’t simply have the highest prison population in western Europe, we also have some of the worst recidivism rates when inmates are released. Twenty five per cent of adult prisoners go on to reoffend. For young offenders the figure is 30%. And for adults released from sentences of less than two years, no less than 50% reoffend.

Yet we know from reams of research that those committing similar offences who are put on community sentences outside prison have lower recidivism rates than their jailed counterparts. Why should this be surprising? As David Waddington, a notably right-wing Conservative Home Secretary said many years ago, ‘Prison is an expensive way of making bad people worse.’

Bereft of proper facilities for education or rehabilitation, strained to breaking point by austerity and neglect, ludicrously portrayed in some media outlets as ‘holiday camps’, and warehousing some of the most damaged individuals in our society, British prisons should be a stain on our collective conscience, and many of the Chief Inspector’s reports a source of national shame. What a tragic farce, then, that in so many cases they don’t even work. It is hardly a shock that many Republican states in the US, Texas included, are moving away from policies of mass incarceration, precisely because the policy is a wasteful use of tax dollars that fails to deliver on its most basic objective – public safety.

Can we learn the same lesson here? Well, perhaps. And an important tell may be the new Prime Minister’s appointment of James Timpson as Prisons Minister in the Ministry of Justice. Sir Keir Starmer is a careful man. At the Bar, he conducted his cases with notable skill and, more importantly, with great strategic sense, planning ahead to see off challenge. He knows very well that Lord Timpson is a formidable prison reformer who believes that only a third of those currently in prison truly belong there. Another third, he believes, should be receiving therapeutic mental health and addiction interventions in the community, and the rest on community sentences.

From what we know of Sir Keir’s attachment to planning and process, and we know quite a lot, it seems most unlikely that he would have brought Lord Timpson into his government if he didn’t intend to give his new prisons minister some space to create a new penal policy, less focused on incarceration and more directed towards punishment and rehabilitation in the community. It seems equally unlikely that Lord Timpson would have accepted this otherwise poisoned appointment in the absence of such assurances from the top.

So what might reform look like? Increased remission, for sure, perhaps as a permanent measure. And doubtless the resurrection of a Chalk proposal, a presumption that the most pointless and destructive sentences, those under 12 months, should be suspended – and even the wider application of this policy to all sentences under two years.

I also expect the government to cease bad faith attacks on judges and the Parole Board, to shift more resource to probation and rehabilitation, to propagandise the waste and destructive failure of prison as a solution to much offending, and to take full advantage of rapid developments in technology to make tagging a real alternative to remand and custody for many who would otherwise be locked up, usually in squalor.

This disaster is a shared responsibility, and it won’t do for the new government to try to blame everything on its immediate predecessor. The truth is that the last Labour government was equally culpable, crudely attacking judges and driving up tariffs, as well as introducing the disastrous sentence of imprisonment for public protection (IPP), and with no adequate prison building programme to house the inmates its policies were creating. If Labour doesn’t now understand and accept its own part in this debacle, it will hardly start from the right place in what must become a shared process of deep and broad reform, a complete change in the way we think about crime and punishment in our country.

Prisons on the point of collapse: On 12 July 2024 the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Shabana Mahmood set out emergency plans to prevent the impending collapse of the criminal justice system – a temporary reduction of the proportion of certain custodial sentences served from 50-40% from September. Speaking at HMP Five Wells in Northamptonshire, the Lord Chancellor said: ‘Let me be clear, this is an emergency measure. This is not a permanent change. I am unapologetic in my belief that criminals must be punished.’

Penal reform ahead? An important tell may be the new Prime Minister’s appointment of James Timpson as Prisons Minister in the Ministry of Justice.

Co-presented by former DPP Ken Macdonald KC and Tim Owen KC, Double Jeopardy: The Law and Politics Podcast goes to the places where law and politics collide. Small boats, climate justice, transgender rights, Israel, and prisons under Labour, have brought Brenda Hale, Kathleen Stock, David Pannick, Alex Chalk, Melanie Phillips and many others to the conversation since 2022.

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier