*/

What promotes/inhibits participation? Penny Cooper examines a new research study and toolkit for those who guide witnesses’ and parties’ participation – now an increasingly significant part of a barrister’s role

Barristers will have direct experience of courts and tribunals supporting witness and party participation eg through the use of interpreters and witness intermediaries, timetabling to accommodate witness availability and, particularly since COVID-19, making directions about virtual attendance. There are also obstacles to participation to be navigated in some cases, eg lack of legal aid and legal representation, and temperamental technology.

Considering the vital role that witnesses and parties play, surprisingly little time has been spent studying their participation in courts and tribunals. My academic colleagues and I at the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research (ICPR) at Birkbeck recently completed a major research project addressing four key questions:

We carried out 159 interviews with barristers, solicitors, judges, magistrates, courts staff and others who work in courts and tribunals and we observed over 300 hours of crime, family, immigration and employment hearings.

Practitioners frequently spoke about the facilitation of court user participation as a significant part of their own and their colleagues’ roles:

‘Lay clients won’t always understand necessarily what they should do, eg simple things like evidential matters… they’re not really participating effectively if they aren’t aware of what they should be putting before the court.’ (barrister; immigration)

‘Going into a court for someone who’s never been in a court, is probably like going somewhere where they speak a foreign language and you don’t speak that language ... It is very alien.’ (solicitor; crime)

‘I think the main thrust is towards making sure that whatever they’re there to do as a witness of fact, they can communicate that.’ (barrister; family)

‘[The defendant] struggled to speak in front of multiple people, and found [eye contact] difficult... I supported the recommendation that he should leave the courtroom and give evidence via live link... [otherwise he] couldn’t do it.’ (intermediary; criminal)

Courteous and respectful treatment of court users was the norm across the range of court and tribunal settings. A great many practitioners dealt with court users in a manner that extended beyond courtesy and respect to kindness and sympathy, and an acknowledgment of the deeply personal and often highly emotive character of what was being addressed in the courtroom.

Observations of hearings provided ample evidence that this task of facilitating participation was indeed taken seriously and effectively carried out. For example, in a crown court trial, a defence barrister took the opportunity of a break in proceedings to tell the judge that his client had been having heart palpitations, at which the judge asked the defendant about his health and added: ‘giving evidence in the Crown Court, whatever the circumstances, is very stressful ... If you feel unwell, please say so.’

In an employment tribunal, the judge took a great deal of care to ensure that all lay users, especially the unrepresented claimant, understood what was happening. The judge offered explanations when it appeared that the claimant did not understand procedure and on a number of occasions told the claimant not to apologise for their lack of understanding. The judge offered to change the lighting level in the hearing room if it would make it easier for the claimant.

Although some judges, lawyers and others sought to explain terminology and processes to court users (and especially litigants in person), there was a notable tendency among many practitioners to default to jargon and complex language.

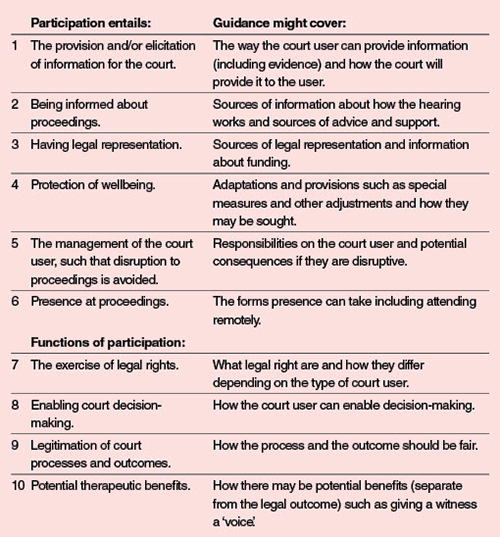

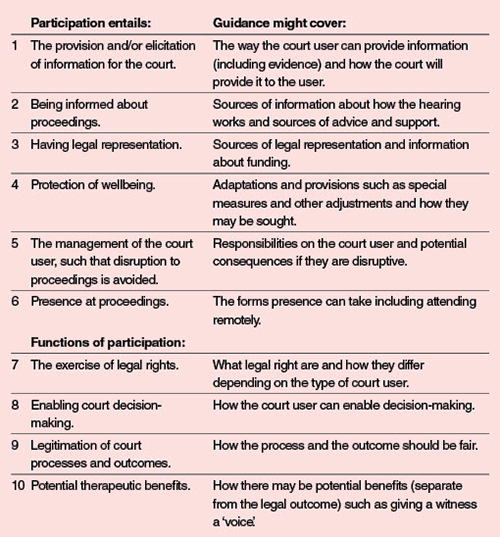

The pandemic is having a major impact on case management. In some types of cases, virtual attendance via video platforms and the use of electronic bundles has become the new normal for trials. In others, courtroom space has been drastically reorganised to allow socially distanced face to face hearings. Despite such changes, the objective is still effective participation. Based on our research, we have devised a provisional framework to assist those who guide witnesses’ and parties’ participation in the hearing process, shown in the box above. This framework, together with many practice examples and details of international innovation, appears in a practitioner toolkit on The Advocate’s Gateway: Supporting Participation in Courts and Tribunals. The toolkit is free to access here.

Barristers will have direct experience of courts and tribunals supporting witness and party participation eg through the use of interpreters and witness intermediaries, timetabling to accommodate witness availability and, particularly since COVID-19, making directions about virtual attendance. There are also obstacles to participation to be navigated in some cases, eg lack of legal aid and legal representation, and temperamental technology.

Considering the vital role that witnesses and parties play, surprisingly little time has been spent studying their participation in courts and tribunals. My academic colleagues and I at the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research (ICPR) at Birkbeck recently completed a major research project addressing four key questions:

We carried out 159 interviews with barristers, solicitors, judges, magistrates, courts staff and others who work in courts and tribunals and we observed over 300 hours of crime, family, immigration and employment hearings.

Practitioners frequently spoke about the facilitation of court user participation as a significant part of their own and their colleagues’ roles:

‘Lay clients won’t always understand necessarily what they should do, eg simple things like evidential matters… they’re not really participating effectively if they aren’t aware of what they should be putting before the court.’ (barrister; immigration)

‘Going into a court for someone who’s never been in a court, is probably like going somewhere where they speak a foreign language and you don’t speak that language ... It is very alien.’ (solicitor; crime)

‘I think the main thrust is towards making sure that whatever they’re there to do as a witness of fact, they can communicate that.’ (barrister; family)

‘[The defendant] struggled to speak in front of multiple people, and found [eye contact] difficult... I supported the recommendation that he should leave the courtroom and give evidence via live link... [otherwise he] couldn’t do it.’ (intermediary; criminal)

Courteous and respectful treatment of court users was the norm across the range of court and tribunal settings. A great many practitioners dealt with court users in a manner that extended beyond courtesy and respect to kindness and sympathy, and an acknowledgment of the deeply personal and often highly emotive character of what was being addressed in the courtroom.

Observations of hearings provided ample evidence that this task of facilitating participation was indeed taken seriously and effectively carried out. For example, in a crown court trial, a defence barrister took the opportunity of a break in proceedings to tell the judge that his client had been having heart palpitations, at which the judge asked the defendant about his health and added: ‘giving evidence in the Crown Court, whatever the circumstances, is very stressful ... If you feel unwell, please say so.’

In an employment tribunal, the judge took a great deal of care to ensure that all lay users, especially the unrepresented claimant, understood what was happening. The judge offered explanations when it appeared that the claimant did not understand procedure and on a number of occasions told the claimant not to apologise for their lack of understanding. The judge offered to change the lighting level in the hearing room if it would make it easier for the claimant.

Although some judges, lawyers and others sought to explain terminology and processes to court users (and especially litigants in person), there was a notable tendency among many practitioners to default to jargon and complex language.

The pandemic is having a major impact on case management. In some types of cases, virtual attendance via video platforms and the use of electronic bundles has become the new normal for trials. In others, courtroom space has been drastically reorganised to allow socially distanced face to face hearings. Despite such changes, the objective is still effective participation. Based on our research, we have devised a provisional framework to assist those who guide witnesses’ and parties’ participation in the hearing process, shown in the box above. This framework, together with many practice examples and details of international innovation, appears in a practitioner toolkit on The Advocate’s Gateway: Supporting Participation in Courts and Tribunals. The toolkit is free to access here.

What promotes/inhibits participation? Penny Cooper examines a new research study and toolkit for those who guide witnesses’ and parties’ participation – now an increasingly significant part of a barrister’s role

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier