*/

Reduction of jury rights will inevitably lead to more miscarriages of justice, says Matt Foot of APPEAL in response to the Leveson Review

Ten years ago, we celebrated the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. The Charter includes Clause 39 stating that no free man could be imprisoned ‘except by the lawful judgment of his peers’ – social equals – ‘or by the law of the land’. The Magna Carta was the first document to put into writing the principle that the king and his government were not above the law. The Magna Carta led to the principle of trial by jury, later confirmed in the Habeas Corpus Act 1679.

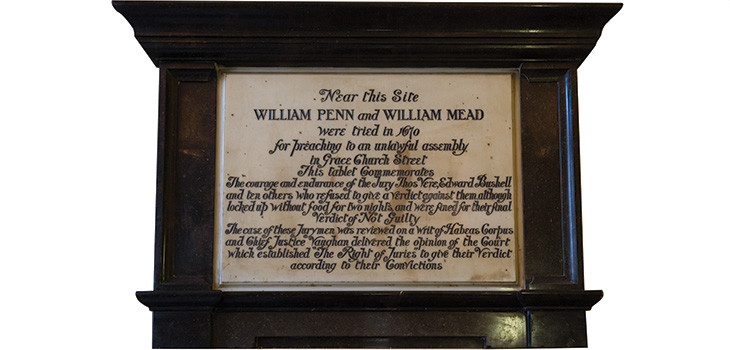

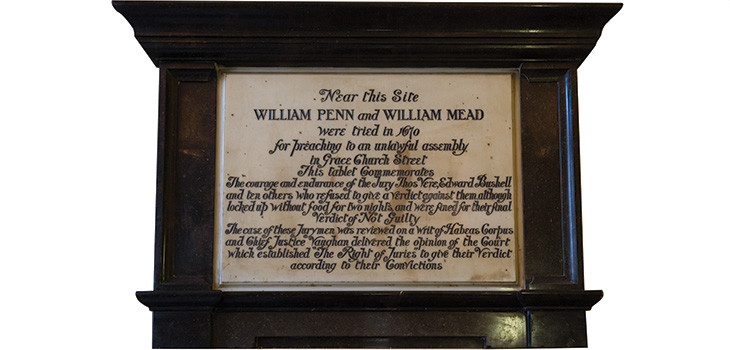

In the Old Bailey there is a stone memorial to perhaps the most famous case in British history, Bushell’s Case ((1670) 124 ER 1006). Edward Bushell was not even on trial; he was a juror, the foreman of the jury. Bushell and his fellow jurors refused to convict two preachers, William Penn and William Mead, for unlawful assembly in the face of demands by the judge to do so. They were all sent to the Tower of London for their obstinance, but refused to buckle. As a result of their bravery they won the right for all future jurors to decide the verdict of those on trial rather than a judge.

That right has been reasserted ever since. As Lord Bingham said in R v Wang [2005] UKHL 9: ‘[The public] over many centuries has adhered tenaciously to its historic choice that decisions on the guilt of defendants charged with serious crime should rest with a jury of lay people, randomly selected, and not with professional judges.’

In the United States, the right to a jury trial in criminal prosecutions is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment.

Prior to the Christmas 2024 break, the Ministry of Justice announced a review to seek answers to the crisis of the 70,000 plus Crown Court trial backlog. The Review being carried out by Sir Brian Leveson seems to prejudge a consultation, prefaced with suggested ‘reforms’ that would seriously undermine the right to a jury trial, by reclassification of offences from triable-either-way to summary only, and the introduction of an intermediate juryless court. The government has called the Review ‘independent’, but should a judge-led review be considering giving more power to judges?

The suggestion that we remove the right to a jury for either-way offences will have a serious impact on a defendant seeking a fair trial. They are serious offences, where loss of liberty is at stake. Violent disorder carries a maximum sentence of five years. In a number of protest trials juries have acquitted protesters charged with violent disorder, whose defence has been of acting in self-defence against the police (including student Alfie Meadows demonstrating against tuition fees and Black Lives Matter protesters). It is doubtful judge-only trials would have reached the same verdict. Civil servant Clive Ponting – acquitted by a jury (of disclosing official secrets about the sinking of the Belgrano in the Falklands War) despite the trial judge directing a conviction – would inevitably have been convicted in a juryless trial.

Many of us have been arguing for years that the court system is in a crisis which needs addressing. Removing jury trial rights is not the answer to that problem. In February, the Bar Council put out an impressive statement in response to the Leveson Review: ‘Changing the fundamental structure of delivering criminal justice is not a principled response to a crisis which was not caused by the structure in the first place.’

Giving judges more power over verdicts raises the issue of judicial bias. In 1976 J.A.G. Griffith wrote his seminal book, The Politics of the Judiciary. Griffith identified the number of judges from public school backgrounds had increased between 1987 and 1994 – from 70% to 80%. While the ratio has changed since, in Elitist Britain? 2014 the Commissions on Social Mobility and Child Poverty reported that 71% of senior judges attended independent schools (compared to 7% of the public as a whole) and 75% attended Oxford or Cambridge (compared to 1% of the public). Only 4% of 150 senior judges went to comprehensive school – the lowest figure for all groups. In Elitist Britain 2019, the Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission found ‘that 65% of the most senior judges in England and Wales went to an “independent school” – more than any other elite profession it looked at’.

The judiciary’s record on renowned miscarriage of justice cases is peppered with injudicious commentary which should provide fair warning against providing them with greater powers to convict.

Lord Denning, who was Master of the Rolls for some 20 years, said of the Birmingham Six in an interview for The Spectator in 1990: ‘We shouldn’t have all these campaigns to get them released if they’d been hanged. They’d have been forgotten and the whole community would have been satisfied.’

Mr Justice Donaldson (later Lord Donaldson, Master of the Rolls for 10 years) said as trial judge for the Guildford Four in 1975: ‘I feel it is my duty to wonder aloud why you were not charged with treason to the Crown, a charge that carries the penalty of death by hanging. A sentence I would have no difficulty passing in this case.’

Over the last few years, we have seen something of a crisis in the police. Serious discrimination within the Metropolitan Police led, in 2023, to the Casey Review which stated things were so bad: ‘The Met can now no longer presume that it has the permission of the people of London to police them. The loss of this crucial principle of policing by consent would be catastrophic. We must make sure it is not irreversible.’

The London Mayor confirmed: ‘The evidence is damning. Baroness Casey has found institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia, which I accept.’

To choose this time to remove the right to jury trial would provide some comfort to the worst elements within the police, who would avoid being held to account by a jury.

Practitioners have long since complained about a number of issues which clearly exacerbate trial delays and the crisis. Between 2010 and 2019, over half the courts across England and Wales were closed. A Daily Telegraph article in October 2024 referred to ‘nearly a third of courtrooms – 158 out of 492… not sitting amid shortages of judges, lawyers, court staff and a cap on government funding’, and ‘one in four trials now doesn’t go ahead as scheduled. A growing reason is a lack of lawyers’. Adjournments are commonplace because of the state of the courts. Getting rid of juries will not solve these problems. The system is chronically underfunded.

At APPEAL we are particularly concerned about the pervasive use of joint enterprise. These cases often result in large-scale trials involving multiple defendants and not infrequently result in acquittals for some, or sometimes even most, of the accused. This is due to the absence of clear evidence demonstrating a significant or direct contribution to the offence.

The right to be tried by your peers remains as relevant to the defendant today as it was in the 1670. The Penn or Mead of today maybe an anti-racist protester, a subpostmaster, or a black defendant discriminated by the police. Any reduction of jury rights will inevitably lead to more miscarriages of justice. The integrity of the criminal justice system is therefore at stake.

Ten years ago, we celebrated the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. The Charter includes Clause 39 stating that no free man could be imprisoned ‘except by the lawful judgment of his peers’ – social equals – ‘or by the law of the land’. The Magna Carta was the first document to put into writing the principle that the king and his government were not above the law. The Magna Carta led to the principle of trial by jury, later confirmed in the Habeas Corpus Act 1679.

In the Old Bailey there is a stone memorial to perhaps the most famous case in British history, Bushell’s Case ((1670) 124 ER 1006). Edward Bushell was not even on trial; he was a juror, the foreman of the jury. Bushell and his fellow jurors refused to convict two preachers, William Penn and William Mead, for unlawful assembly in the face of demands by the judge to do so. They were all sent to the Tower of London for their obstinance, but refused to buckle. As a result of their bravery they won the right for all future jurors to decide the verdict of those on trial rather than a judge.

That right has been reasserted ever since. As Lord Bingham said in R v Wang [2005] UKHL 9: ‘[The public] over many centuries has adhered tenaciously to its historic choice that decisions on the guilt of defendants charged with serious crime should rest with a jury of lay people, randomly selected, and not with professional judges.’

In the United States, the right to a jury trial in criminal prosecutions is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment.

Prior to the Christmas 2024 break, the Ministry of Justice announced a review to seek answers to the crisis of the 70,000 plus Crown Court trial backlog. The Review being carried out by Sir Brian Leveson seems to prejudge a consultation, prefaced with suggested ‘reforms’ that would seriously undermine the right to a jury trial, by reclassification of offences from triable-either-way to summary only, and the introduction of an intermediate juryless court. The government has called the Review ‘independent’, but should a judge-led review be considering giving more power to judges?

The suggestion that we remove the right to a jury for either-way offences will have a serious impact on a defendant seeking a fair trial. They are serious offences, where loss of liberty is at stake. Violent disorder carries a maximum sentence of five years. In a number of protest trials juries have acquitted protesters charged with violent disorder, whose defence has been of acting in self-defence against the police (including student Alfie Meadows demonstrating against tuition fees and Black Lives Matter protesters). It is doubtful judge-only trials would have reached the same verdict. Civil servant Clive Ponting – acquitted by a jury (of disclosing official secrets about the sinking of the Belgrano in the Falklands War) despite the trial judge directing a conviction – would inevitably have been convicted in a juryless trial.

Many of us have been arguing for years that the court system is in a crisis which needs addressing. Removing jury trial rights is not the answer to that problem. In February, the Bar Council put out an impressive statement in response to the Leveson Review: ‘Changing the fundamental structure of delivering criminal justice is not a principled response to a crisis which was not caused by the structure in the first place.’

Giving judges more power over verdicts raises the issue of judicial bias. In 1976 J.A.G. Griffith wrote his seminal book, The Politics of the Judiciary. Griffith identified the number of judges from public school backgrounds had increased between 1987 and 1994 – from 70% to 80%. While the ratio has changed since, in Elitist Britain? 2014 the Commissions on Social Mobility and Child Poverty reported that 71% of senior judges attended independent schools (compared to 7% of the public as a whole) and 75% attended Oxford or Cambridge (compared to 1% of the public). Only 4% of 150 senior judges went to comprehensive school – the lowest figure for all groups. In Elitist Britain 2019, the Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission found ‘that 65% of the most senior judges in England and Wales went to an “independent school” – more than any other elite profession it looked at’.

The judiciary’s record on renowned miscarriage of justice cases is peppered with injudicious commentary which should provide fair warning against providing them with greater powers to convict.

Lord Denning, who was Master of the Rolls for some 20 years, said of the Birmingham Six in an interview for The Spectator in 1990: ‘We shouldn’t have all these campaigns to get them released if they’d been hanged. They’d have been forgotten and the whole community would have been satisfied.’

Mr Justice Donaldson (later Lord Donaldson, Master of the Rolls for 10 years) said as trial judge for the Guildford Four in 1975: ‘I feel it is my duty to wonder aloud why you were not charged with treason to the Crown, a charge that carries the penalty of death by hanging. A sentence I would have no difficulty passing in this case.’

Over the last few years, we have seen something of a crisis in the police. Serious discrimination within the Metropolitan Police led, in 2023, to the Casey Review which stated things were so bad: ‘The Met can now no longer presume that it has the permission of the people of London to police them. The loss of this crucial principle of policing by consent would be catastrophic. We must make sure it is not irreversible.’

The London Mayor confirmed: ‘The evidence is damning. Baroness Casey has found institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia, which I accept.’

To choose this time to remove the right to jury trial would provide some comfort to the worst elements within the police, who would avoid being held to account by a jury.

Practitioners have long since complained about a number of issues which clearly exacerbate trial delays and the crisis. Between 2010 and 2019, over half the courts across England and Wales were closed. A Daily Telegraph article in October 2024 referred to ‘nearly a third of courtrooms – 158 out of 492… not sitting amid shortages of judges, lawyers, court staff and a cap on government funding’, and ‘one in four trials now doesn’t go ahead as scheduled. A growing reason is a lack of lawyers’. Adjournments are commonplace because of the state of the courts. Getting rid of juries will not solve these problems. The system is chronically underfunded.

At APPEAL we are particularly concerned about the pervasive use of joint enterprise. These cases often result in large-scale trials involving multiple defendants and not infrequently result in acquittals for some, or sometimes even most, of the accused. This is due to the absence of clear evidence demonstrating a significant or direct contribution to the offence.

The right to be tried by your peers remains as relevant to the defendant today as it was in the 1670. The Penn or Mead of today maybe an anti-racist protester, a subpostmaster, or a black defendant discriminated by the police. Any reduction of jury rights will inevitably lead to more miscarriages of justice. The integrity of the criminal justice system is therefore at stake.

Reduction of jury rights will inevitably lead to more miscarriages of justice, says Matt Foot of APPEAL in response to the Leveson Review

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier