*/

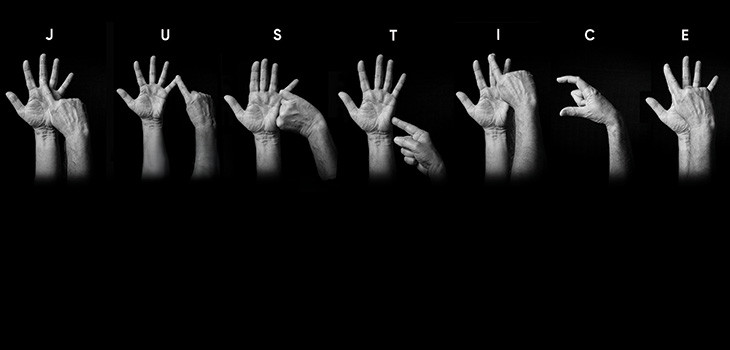

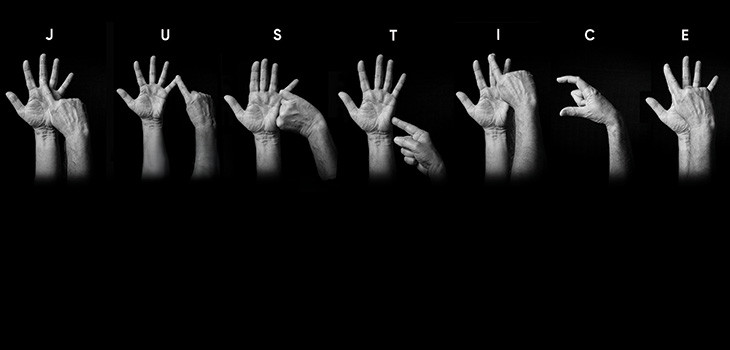

The deaf community, like many marginalised communities, has long struggled to access legal services. An obvious barrier is communication. This is true for deaf people who rely on speech and lipreading, and perhaps more obvious for those for whom British Sign Language (BSL) is their preferred (and/or only) language. Arguably, the more significant barrier is that of awareness: how to communicate with deaf people, how to facilitate communication with deaf people, what the lived experiences are for deaf people, among other things. These barriers can be incredibly frustrating for lawyers who are approached by prospective deaf clients. These barriers are also incredibly frustrating, and potentially defining, for those deaf people who need to encounter legal professionals (as of course we all do at some point).

Prior to starting my pupillage at Garden Court Chambers in October 2023, I worked as a sign language interpreter for 20 years. My relationship with, and ‘membership’ of, the deaf community derives from my parents, who are both profoundly deaf. BSL is my native language. My experiences of growing up with deaf parents, surrounded by deaf friends and the wider deaf community, alongside my professional experiences working as a sign language interpreter (both domestically and internationally), regularly highlighted the need to improve the access of deaf individuals and communities to legal professionals. This was lacking at all levels, from the grassroots through to community leadership.

One of my main drivers for retraining and coming to the Bar was an attempt to provide some sort of bridge between deaf communities and legal professionals. As with most barriers, the creation of the barriers faced by deaf people might have been contrived at some point in time, but their continued presence is not, generally, malevolent. How should we overcome these barriers?

After starting my pupillage, I was approached by Ollie Persey, a fellow member of Chambers, who had the idea of holding a panel event specifically focused on deaf people. On 29 February 2024, we hosted an event entitled ‘Access to Justice for Deaf Communities’. The event was incredibly well attended by representatives from deaf civil society, deaf individuals and lawyers. At the end of the panel, we had a question-and-answer session. Overwhelmingly, deaf people spoke of encountering barriers for everyday legal tasks, such as creating a will. The main issue being that solicitors’ firms were not willing to provide (i.e. pay for) sign language interpreters. Individuals were regularly asked to provide family members to assist, which, as the individuals articulated, was often completely inappropriate. This situation is writ large across other services, such as medical or local authority appointments. The wider problem articulated was that deaf people feel as though they cannot access the legal profession for everyday legal tasks, let alone to assist with enforcing and/or advocating for rights across other services.

Consequently, Chambers convened a forum, the Deaf Legal Network (DLN), designed to bring together representatives from deaf-led organisations and lawyers. The first meeting was held on 28 June 2024. The three aims of DLN are to:

In the first instance, this forum provides a network that lawyers and members of deaf civil society can engage with for signposting, information and advice. The main purpose is to create a space where deaf people and lawyers can learn from each other.

DLN wants to bring together experiences, knowledge and best practice. As a collaboration between lawyers and representatives of deaf communities, DLN meets regularly through the year. Ahead of each meeting, representatives of deaf-led organisations are consulted on specific topics to be covered in the meeting, with the intention of having presentations on those topics. For example, at the event in February 2024, we hosted presentations on bringing Equality Act (2010) claims and raising judicial reviews to challenge discriminatory treatment.

The longer-term aim is to create a central resource for deaf people and lawyers, available in BSL and English, that will share this information and best practice.

DLN is in the process of establishing a referral mechanism to ensure that deaf people can receive legal advice and representation. Chambers coordinates a similar referral mechanism within the School Inclusion Project. Work is currently under way to ensure that this is created in a way that is appropriate for the needs of deaf people, including a provision for referrals in BSL.

A key benefit of the network is the opportunity to bring stakeholders together. This will enable conversations about how the law can be used to addressed systemic unfairness experienced by deaf communities. Recent positive examples of using the law in this respect include: Reynolds et al v Live in the UK Ltd (2020) and R (on the application of Katherine Rowley) v Minister for the Cabinet Office [2021] EWHC 2108 (Admin).

In Reynolds, three deaf mothers had booked to take their hearing children to a Little Mix music concert. They requested that sign language interpreters were provided. The organiser originally refused, instead offering carer tickets so that the mothers could provide their own interpreters. In the end, the organiser provided an interpreter for the Little Mix performance, but not for the warm-up acts or arena announcements. In the county court, District Judge Avent held that the organisers had discriminated against the three deaf mothers by failing to provide interpreters for the duration of the whole concert.

In Rowley, Mr Justice Fordham ruled that the Cabinet Office had discriminated against Ms Rowley, a deaf woman, by failing to make reasonable adjustments in respect of two science data briefings that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither of these science data briefings were interpreted into BSL.

It is well worth noting that following these cases, the availability of sign language interpreters for music concerts, and other such entertainment events, and government broadcasts has increased.

Ultimately, our purpose is to give deaf people a seat at the table in relation to access to justice. We will take a strategic approach to challenging systemic unfairness experienced by deaf communities. Further, the aim is to share knowledge and best practice with legal professionals, empowering professionals to provide the best support and client care possible.

To find out more about how you can get involved, please visit the Garden Court Chambers website here.

The deaf community, like many marginalised communities, has long struggled to access legal services. An obvious barrier is communication. This is true for deaf people who rely on speech and lipreading, and perhaps more obvious for those for whom British Sign Language (BSL) is their preferred (and/or only) language. Arguably, the more significant barrier is that of awareness: how to communicate with deaf people, how to facilitate communication with deaf people, what the lived experiences are for deaf people, among other things. These barriers can be incredibly frustrating for lawyers who are approached by prospective deaf clients. These barriers are also incredibly frustrating, and potentially defining, for those deaf people who need to encounter legal professionals (as of course we all do at some point).

Prior to starting my pupillage at Garden Court Chambers in October 2023, I worked as a sign language interpreter for 20 years. My relationship with, and ‘membership’ of, the deaf community derives from my parents, who are both profoundly deaf. BSL is my native language. My experiences of growing up with deaf parents, surrounded by deaf friends and the wider deaf community, alongside my professional experiences working as a sign language interpreter (both domestically and internationally), regularly highlighted the need to improve the access of deaf individuals and communities to legal professionals. This was lacking at all levels, from the grassroots through to community leadership.

One of my main drivers for retraining and coming to the Bar was an attempt to provide some sort of bridge between deaf communities and legal professionals. As with most barriers, the creation of the barriers faced by deaf people might have been contrived at some point in time, but their continued presence is not, generally, malevolent. How should we overcome these barriers?

After starting my pupillage, I was approached by Ollie Persey, a fellow member of Chambers, who had the idea of holding a panel event specifically focused on deaf people. On 29 February 2024, we hosted an event entitled ‘Access to Justice for Deaf Communities’. The event was incredibly well attended by representatives from deaf civil society, deaf individuals and lawyers. At the end of the panel, we had a question-and-answer session. Overwhelmingly, deaf people spoke of encountering barriers for everyday legal tasks, such as creating a will. The main issue being that solicitors’ firms were not willing to provide (i.e. pay for) sign language interpreters. Individuals were regularly asked to provide family members to assist, which, as the individuals articulated, was often completely inappropriate. This situation is writ large across other services, such as medical or local authority appointments. The wider problem articulated was that deaf people feel as though they cannot access the legal profession for everyday legal tasks, let alone to assist with enforcing and/or advocating for rights across other services.

Consequently, Chambers convened a forum, the Deaf Legal Network (DLN), designed to bring together representatives from deaf-led organisations and lawyers. The first meeting was held on 28 June 2024. The three aims of DLN are to:

In the first instance, this forum provides a network that lawyers and members of deaf civil society can engage with for signposting, information and advice. The main purpose is to create a space where deaf people and lawyers can learn from each other.

DLN wants to bring together experiences, knowledge and best practice. As a collaboration between lawyers and representatives of deaf communities, DLN meets regularly through the year. Ahead of each meeting, representatives of deaf-led organisations are consulted on specific topics to be covered in the meeting, with the intention of having presentations on those topics. For example, at the event in February 2024, we hosted presentations on bringing Equality Act (2010) claims and raising judicial reviews to challenge discriminatory treatment.

The longer-term aim is to create a central resource for deaf people and lawyers, available in BSL and English, that will share this information and best practice.

DLN is in the process of establishing a referral mechanism to ensure that deaf people can receive legal advice and representation. Chambers coordinates a similar referral mechanism within the School Inclusion Project. Work is currently under way to ensure that this is created in a way that is appropriate for the needs of deaf people, including a provision for referrals in BSL.

A key benefit of the network is the opportunity to bring stakeholders together. This will enable conversations about how the law can be used to addressed systemic unfairness experienced by deaf communities. Recent positive examples of using the law in this respect include: Reynolds et al v Live in the UK Ltd (2020) and R (on the application of Katherine Rowley) v Minister for the Cabinet Office [2021] EWHC 2108 (Admin).

In Reynolds, three deaf mothers had booked to take their hearing children to a Little Mix music concert. They requested that sign language interpreters were provided. The organiser originally refused, instead offering carer tickets so that the mothers could provide their own interpreters. In the end, the organiser provided an interpreter for the Little Mix performance, but not for the warm-up acts or arena announcements. In the county court, District Judge Avent held that the organisers had discriminated against the three deaf mothers by failing to provide interpreters for the duration of the whole concert.

In Rowley, Mr Justice Fordham ruled that the Cabinet Office had discriminated against Ms Rowley, a deaf woman, by failing to make reasonable adjustments in respect of two science data briefings that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither of these science data briefings were interpreted into BSL.

It is well worth noting that following these cases, the availability of sign language interpreters for music concerts, and other such entertainment events, and government broadcasts has increased.

Ultimately, our purpose is to give deaf people a seat at the table in relation to access to justice. We will take a strategic approach to challenging systemic unfairness experienced by deaf communities. Further, the aim is to share knowledge and best practice with legal professionals, empowering professionals to provide the best support and client care possible.

To find out more about how you can get involved, please visit the Garden Court Chambers website here.

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier