*/

Michael Jennings and Patrick Walker respond to the snapshot findings: while financial security, work/life balance and variety of work are encouraging barristers to take the in-house route, significant frustrations were also reported

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Michael Jennings, Chair of the Employed Barristers’ Committee, responds to the snapshot survey findings and outlines steps being taken to address the concerns raised

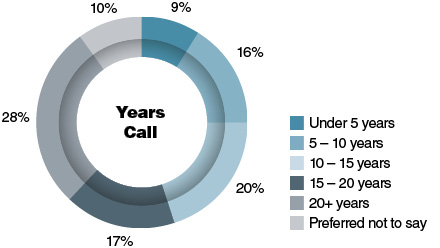

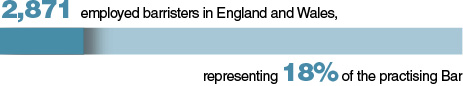

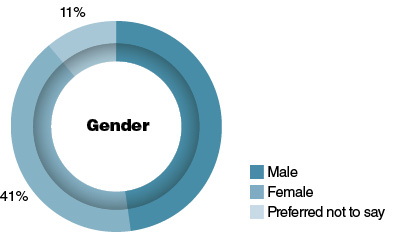

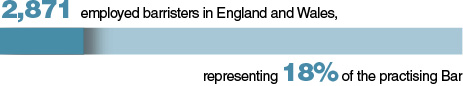

The Employed Barristers’ Committee (EBC) now represents a community which is just under 20% of the Bar as a whole. We felt it was necessary to carry out a survey of the employed Bar, to identify the concerns and interests of employed barristers, allowing both the EBC and wider Bar Council to be better placed to assist that community. The survey results led to the publication of our Snapshot Report: The Experiences of Employed Barristers at the Bar, which was published in November 2016 and will help frame the committee’s work over the coming year.

This report provides plenty of food for thought, not only for the EBC, but also the Bar Council as a whole. We noted from the results and comments that there is much to commend the work and role of the employed barrister. As we saw with last year’s Bar Council wellbeing survey, the employed Bar has some of the highest levels of engagement and satisfaction with the work they do.

The sky is not entirely cloud free. It is troubling that members of the employed Bar reported that they still encountered, or at the very least perceived, the view that somehow their work is of lower value or less respected than that of the self-employed Bar. Good work has been undertaken in this field and the Bar Council has done much to encourage not only inclusiveness, but also recognition of the valuable work of the employed Bar. As the employed Bar continues to grow, and crossover between the two branches of the Bar family increase, it is to be hoped that this perception will reduce. The accusatory finger is often pointed at the self-employed Bar, which is blamed for maintaining historic misconceptions about the employed Bar. There may be some truth in that, but the employed Bar is equally culpable if it fails effectively to engage with the wider Bar.

It was a concern to read that many employed barristers believe that opportunities at the employed Bar are not sufficiently publicised to students entering the profession. This was considered to be a failure on the part of employers, Bar professional training course providers and a general lack of a publicity about the opportunities at the employed Bar at pupillage fairs and by the Inns. As employed barristers, we need to engage more actively and effectively with the work of the Bar, the Circuits and the Inns. We need to demonstrate that we are active and key players within the community of the Bar. Employed barristers need to get involved. The more visible they are, the greater will be the knowledge of who and what they are and inevitably, such exposure will increase mutual respect and confidence.

The report also revealed that employed barristers feel they are held back when applying for QC appointments and judicial posts. The committee is very conscious of these concerns and over the past year has met with the Law Officers, the Chairman of the Bar, the Judicial Appointments Commission and others to work out how best to increase opportunities for the employed Bar. This is very much a work in progress, but progress has been made. The Bar Council offers a silk and judicial mentoring service, which is recommended to all those interested in following the path to the bench or to Silk.

The committee has taken several steps to address the concerns raised in the report. As the findings showed that many employed barristers want greater recognition and support from the Bar Council, the committee has set up a LinkedIn ‘Employed Barristers Network’. This network allows members of the employed Bar to interact with each other and the committee, encouraging greater communication between the employed Bar and the Bar Council. We would encourage employed barristers to engage with us in this network, as it is a valuable opportunity to bring the employed Bar and Bar Council closer together. The committee has also re-launched the bimonthly newsletter, which has been positively received. We continue to receive subscription requests for the newsletter, as well as employed barristers offering their time to become more involved with the work of the committee.

To address the issue of recognition, the Bar Council will also be hosting its first ‘awards ceremony’ for the employed Bar. The committtee’s policy analyst, Dominique Smith (DSmith@BarCouncil.org.uk), will be releasing details shortly.

Finally, the Bar Council is considering to run a scheme that would facilitate both employed and self-employed barristers to undertake a secondment in a chambers or in an organisation. The committee will, in due course, consult with the Leaders of each Circuit, as well as various employers, whose goodwill and encouragement is likely to be invaluable.

Contributor Michael Jennings, Chair of the Employed Barristers’ Committee

UNDER-EMPLOYED?

Mediator and Recorder Patrick Walker reviews the snapshot survey report in the light of his own experience at the employed Bar

The day I announced my departure for the employed Bar, reactions ranged from anger that I was betraying the ‘independent’ Bar to sympathy for a colleague who had lost his marbles. Few thought it a good move, but I was excited by the opportunity to advocate whilst working in an energetic and talented team in a large solicitors’ firm. That opportunity had just been created by the Access to Justice Act 1999, and 17 years on I read the report on the employed Bar with interest, some pleasure and a measure of frustration.

Let’s start with the frustration. Treating the employed Bar as inferior has been a pastime for more insecure members of our profession for years. My own experience has been of a steady, if rather slow, improvement of relations and respect – to a point where most judges really do not care whether the advocate is self-employed, or a solicitor for that matter, provided they are well prepared and reasonably able. How different from the early days when I was not allowed to be marked on the court list as ‘counsel’, and my right of audience was periodically challenged, even though I had spent 20 years in chambers. Further, the migration of those including senior Silks to and from law firms demonstrates acknowledgment of employed status as a real alternative, which is in no way second best. Against this experience, it is sad to read comments in the report suggesting continuing contempt towards some employed barristers. Even if to some extent they reflect a separate tension between some members of the criminal Bar and the CPS, they are unacceptable.

My own experience is that employed status has not precluded judicial appointment, but it is difficult to know how far I would have got without a previous track record in chambers. But I suspect the real debate in respect of both judicial and Silk appointments is not the significance of employed status, but the extent to which the words of the Judicial Appointments Commission – that candidates are selected ‘on merit, through fair and open competition, from the widest range of eligible candidates’ – are converted into action. However widely drafted the eligibility criteria may be, individuals and groups whose skills and experience are misunderstood or hidden away in a corner are always going to struggle to win appointments in a tough and competitive arena.

At this point I must echo the words of Michael Jennings (Chair of the EBC, of which I was a founder member in 1999), that the employed Bar must engage more actively with the Bar, the Circuits and the Inns. Further, in my view such engagement must be in all areas, and not only those provided for the employed Bar. Other activities may be aimed primarily at the 80% of members in chambers, but that is inevitable and doesn’t mean there isn’t value for all of us. I confess a degree of hypocrisy in this advice, and I wonder if I am alone in having enjoyed the security, variety and interest that my employment has offered, but have then found too little time for my Inn and Circuit, both of which have worked to become more inclusive and welcoming. The suggestion that the ‘Inns ignore us’ is certainly an unfair charge against my own Inn (Lincolns). I agree with some other comments that we are sometimes treated as having left the Bar, but that is not only by other barristers. Every such comment is an opportunity not only to correct the misunderstanding, but to explain what we do and how others may find a rewarding career outside of chambers.

When the EBC was formed we hoped that within a few years it would be rendered obsolete by integration of barristers pursuing many different careers in what could truly be called ‘One Bar’. That objective was delayed in the early years by prejudice and lip service but I am optimistic that if such barriers remain, they are insubstantial and ready to be overcome by anyone with sufficient energy and enthusiasm. I am happy to be a member of the employed Bar, but I am much happier and proud to be a member of the Bar.

Contributor Patrick Walker, Mediator and Recorder

THE ATTRACTIONS OF EMPLOYED PRACTICE

SNAPSHOT REPORT: THE EXPERIENCES OF EMPLOYED BARRISTERS AT THE BAR

ON ONE BAR

‘There is a definite perception that the employed Bar attracts only mediocre lawyers or those who are seeking more favourable working conditions. This does not reflect the reality of life at the employed Bar where practitioners can have similar caseloads to those at the independent Bar and are often required to gain a knowledge of, and advise on, complex and specialist areas of law.’

‘I think we’re considered by many to be failed proper barristers, not-up-to-it, not really barristers, not advocates, actually a solicitor…’

‘I feel very much disconnected from the Bar as a whole. I rarely read emails or other Bar Council publications and struggle to see the relevance of the profession to my day-to-day life and work.’

‘[Employed barristers] are considered by some not to be “proper” barristers, but this is changing and has come a long way in the last five years.’

‘It would be good to create a community of employed barristers across all sectors and areas of expertise. I think we all feel quite isolated from the profession.’

‘I think things have changed and there appears to be more acceptance, especially as there are more events done jointly; with the changes in legal aid, this has also made the employed Bar appear more attractive.’

‘The naval Bar enjoys close links with several leading sets of chambers at the private criminal Bar and there is mutual respect, based on the different functions we deliver.’

SALARY

16% of respondents were paid a gross salary in excess of £100,000 a year. 6% of respondents received a gross salary in excess of £150,000. Of those on a gross salary over £150,000, 50% worked in-house at a company.

Average estimated gross salaries:

ON SILK

‘The QC process relies too much on courtroom advocacy. Most of the employed Bar do not do this, so our skills are not recognised.’

‘I was told I had dealt with good credible cases and could apply for Silk, but I saw no reason to do so as there is no real benefit. In fact, in some cases, it causes a problem as you are viewed as too expensive.’

‘It does not appear that the work I do lends itself to the evidence that is required, as the focus appears to be on advocacy and court appearances – my practice is not that way inclined.’

‘I had not considered applying for Silk as I am not experienced enough to meet the threshold for applying. Once I reach this stage, it is something I may consider.’

RANGE OF WORK AND WORKING CONDITIONS

‘The work is more interesting and varied than anything at the self-employed Bar, plus there are other concomitant advantages – regular income, pension, good work-life balance, supportive colleagues…’

‘[There was] insufficient interesting work at the junior Bar at the time I qualified... At the employed Bar, there was the prospect to make a direct impact on local government policy.’

‘Working as part of a team with other colleagues; we share each other’s successes, help each other and work together on difficult issues.’

‘[I value] the compatibility with family life. The nature of my workload and working conditions at the independent Bar would not have been compatible with caring for young children.’

JUDICIAL APPOINTMENT

Michael Jennings, Chair of the Employed Barristers’ Committee, responds to the snapshot survey findings and outlines steps being taken to address the concerns raised

The Employed Barristers’ Committee (EBC) now represents a community which is just under 20% of the Bar as a whole. We felt it was necessary to carry out a survey of the employed Bar, to identify the concerns and interests of employed barristers, allowing both the EBC and wider Bar Council to be better placed to assist that community. The survey results led to the publication of our Snapshot Report: The Experiences of Employed Barristers at the Bar, which was published in November 2016 and will help frame the committee’s work over the coming year.

This report provides plenty of food for thought, not only for the EBC, but also the Bar Council as a whole. We noted from the results and comments that there is much to commend the work and role of the employed barrister. As we saw with last year’s Bar Council wellbeing survey, the employed Bar has some of the highest levels of engagement and satisfaction with the work they do.

The sky is not entirely cloud free. It is troubling that members of the employed Bar reported that they still encountered, or at the very least perceived, the view that somehow their work is of lower value or less respected than that of the self-employed Bar. Good work has been undertaken in this field and the Bar Council has done much to encourage not only inclusiveness, but also recognition of the valuable work of the employed Bar. As the employed Bar continues to grow, and crossover between the two branches of the Bar family increase, it is to be hoped that this perception will reduce. The accusatory finger is often pointed at the self-employed Bar, which is blamed for maintaining historic misconceptions about the employed Bar. There may be some truth in that, but the employed Bar is equally culpable if it fails effectively to engage with the wider Bar.

It was a concern to read that many employed barristers believe that opportunities at the employed Bar are not sufficiently publicised to students entering the profession. This was considered to be a failure on the part of employers, Bar professional training course providers and a general lack of a publicity about the opportunities at the employed Bar at pupillage fairs and by the Inns. As employed barristers, we need to engage more actively and effectively with the work of the Bar, the Circuits and the Inns. We need to demonstrate that we are active and key players within the community of the Bar. Employed barristers need to get involved. The more visible they are, the greater will be the knowledge of who and what they are and inevitably, such exposure will increase mutual respect and confidence.

The report also revealed that employed barristers feel they are held back when applying for QC appointments and judicial posts. The committee is very conscious of these concerns and over the past year has met with the Law Officers, the Chairman of the Bar, the Judicial Appointments Commission and others to work out how best to increase opportunities for the employed Bar. This is very much a work in progress, but progress has been made. The Bar Council offers a silk and judicial mentoring service, which is recommended to all those interested in following the path to the bench or to Silk.

The committee has taken several steps to address the concerns raised in the report. As the findings showed that many employed barristers want greater recognition and support from the Bar Council, the committee has set up a LinkedIn ‘Employed Barristers Network’. This network allows members of the employed Bar to interact with each other and the committee, encouraging greater communication between the employed Bar and the Bar Council. We would encourage employed barristers to engage with us in this network, as it is a valuable opportunity to bring the employed Bar and Bar Council closer together. The committee has also re-launched the bimonthly newsletter, which has been positively received. We continue to receive subscription requests for the newsletter, as well as employed barristers offering their time to become more involved with the work of the committee.

To address the issue of recognition, the Bar Council will also be hosting its first ‘awards ceremony’ for the employed Bar. The committtee’s policy analyst, Dominique Smith (DSmith@BarCouncil.org.uk), will be releasing details shortly.

Finally, the Bar Council is considering to run a scheme that would facilitate both employed and self-employed barristers to undertake a secondment in a chambers or in an organisation. The committee will, in due course, consult with the Leaders of each Circuit, as well as various employers, whose goodwill and encouragement is likely to be invaluable.

Contributor Michael Jennings, Chair of the Employed Barristers’ Committee

UNDER-EMPLOYED?

Mediator and Recorder Patrick Walker reviews the snapshot survey report in the light of his own experience at the employed Bar

The day I announced my departure for the employed Bar, reactions ranged from anger that I was betraying the ‘independent’ Bar to sympathy for a colleague who had lost his marbles. Few thought it a good move, but I was excited by the opportunity to advocate whilst working in an energetic and talented team in a large solicitors’ firm. That opportunity had just been created by the Access to Justice Act 1999, and 17 years on I read the report on the employed Bar with interest, some pleasure and a measure of frustration.

Let’s start with the frustration. Treating the employed Bar as inferior has been a pastime for more insecure members of our profession for years. My own experience has been of a steady, if rather slow, improvement of relations and respect – to a point where most judges really do not care whether the advocate is self-employed, or a solicitor for that matter, provided they are well prepared and reasonably able. How different from the early days when I was not allowed to be marked on the court list as ‘counsel’, and my right of audience was periodically challenged, even though I had spent 20 years in chambers. Further, the migration of those including senior Silks to and from law firms demonstrates acknowledgment of employed status as a real alternative, which is in no way second best. Against this experience, it is sad to read comments in the report suggesting continuing contempt towards some employed barristers. Even if to some extent they reflect a separate tension between some members of the criminal Bar and the CPS, they are unacceptable.

My own experience is that employed status has not precluded judicial appointment, but it is difficult to know how far I would have got without a previous track record in chambers. But I suspect the real debate in respect of both judicial and Silk appointments is not the significance of employed status, but the extent to which the words of the Judicial Appointments Commission – that candidates are selected ‘on merit, through fair and open competition, from the widest range of eligible candidates’ – are converted into action. However widely drafted the eligibility criteria may be, individuals and groups whose skills and experience are misunderstood or hidden away in a corner are always going to struggle to win appointments in a tough and competitive arena.

At this point I must echo the words of Michael Jennings (Chair of the EBC, of which I was a founder member in 1999), that the employed Bar must engage more actively with the Bar, the Circuits and the Inns. Further, in my view such engagement must be in all areas, and not only those provided for the employed Bar. Other activities may be aimed primarily at the 80% of members in chambers, but that is inevitable and doesn’t mean there isn’t value for all of us. I confess a degree of hypocrisy in this advice, and I wonder if I am alone in having enjoyed the security, variety and interest that my employment has offered, but have then found too little time for my Inn and Circuit, both of which have worked to become more inclusive and welcoming. The suggestion that the ‘Inns ignore us’ is certainly an unfair charge against my own Inn (Lincolns). I agree with some other comments that we are sometimes treated as having left the Bar, but that is not only by other barristers. Every such comment is an opportunity not only to correct the misunderstanding, but to explain what we do and how others may find a rewarding career outside of chambers.

When the EBC was formed we hoped that within a few years it would be rendered obsolete by integration of barristers pursuing many different careers in what could truly be called ‘One Bar’. That objective was delayed in the early years by prejudice and lip service but I am optimistic that if such barriers remain, they are insubstantial and ready to be overcome by anyone with sufficient energy and enthusiasm. I am happy to be a member of the employed Bar, but I am much happier and proud to be a member of the Bar.

Contributor Patrick Walker, Mediator and Recorder

THE ATTRACTIONS OF EMPLOYED PRACTICE

SNAPSHOT REPORT: THE EXPERIENCES OF EMPLOYED BARRISTERS AT THE BAR

ON ONE BAR

‘There is a definite perception that the employed Bar attracts only mediocre lawyers or those who are seeking more favourable working conditions. This does not reflect the reality of life at the employed Bar where practitioners can have similar caseloads to those at the independent Bar and are often required to gain a knowledge of, and advise on, complex and specialist areas of law.’

‘I think we’re considered by many to be failed proper barristers, not-up-to-it, not really barristers, not advocates, actually a solicitor…’

‘I feel very much disconnected from the Bar as a whole. I rarely read emails or other Bar Council publications and struggle to see the relevance of the profession to my day-to-day life and work.’

‘[Employed barristers] are considered by some not to be “proper” barristers, but this is changing and has come a long way in the last five years.’

‘It would be good to create a community of employed barristers across all sectors and areas of expertise. I think we all feel quite isolated from the profession.’

‘I think things have changed and there appears to be more acceptance, especially as there are more events done jointly; with the changes in legal aid, this has also made the employed Bar appear more attractive.’

‘The naval Bar enjoys close links with several leading sets of chambers at the private criminal Bar and there is mutual respect, based on the different functions we deliver.’

SALARY

16% of respondents were paid a gross salary in excess of £100,000 a year. 6% of respondents received a gross salary in excess of £150,000. Of those on a gross salary over £150,000, 50% worked in-house at a company.

Average estimated gross salaries:

ON SILK

‘The QC process relies too much on courtroom advocacy. Most of the employed Bar do not do this, so our skills are not recognised.’

‘I was told I had dealt with good credible cases and could apply for Silk, but I saw no reason to do so as there is no real benefit. In fact, in some cases, it causes a problem as you are viewed as too expensive.’

‘It does not appear that the work I do lends itself to the evidence that is required, as the focus appears to be on advocacy and court appearances – my practice is not that way inclined.’

‘I had not considered applying for Silk as I am not experienced enough to meet the threshold for applying. Once I reach this stage, it is something I may consider.’

RANGE OF WORK AND WORKING CONDITIONS

‘The work is more interesting and varied than anything at the self-employed Bar, plus there are other concomitant advantages – regular income, pension, good work-life balance, supportive colleagues…’

‘[There was] insufficient interesting work at the junior Bar at the time I qualified... At the employed Bar, there was the prospect to make a direct impact on local government policy.’

‘Working as part of a team with other colleagues; we share each other’s successes, help each other and work together on difficult issues.’

‘[I value] the compatibility with family life. The nature of my workload and working conditions at the independent Bar would not have been compatible with caring for young children.’

JUDICIAL APPOINTMENT

Michael Jennings and Patrick Walker respond to the snapshot findings: while financial security, work/life balance and variety of work are encouraging barristers to take the in-house route, significant frustrations were also reported

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier