*/

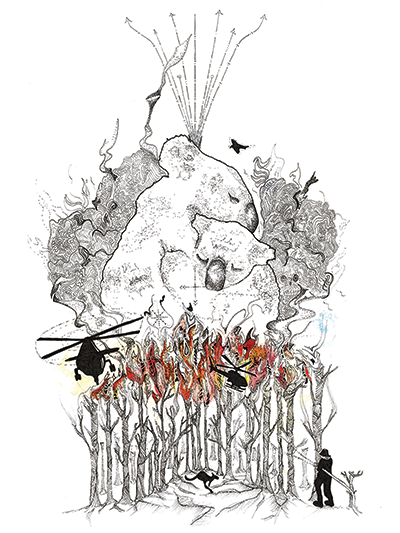

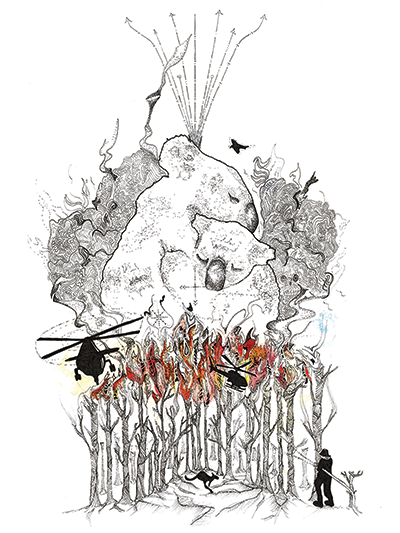

Readers of Counsel do not need to be told about the impact of climate change – our festive periods were coloured by the numerous reports and images of the deadly wildfires in Australia; and the rising sea level is an immediate existential threat for those living on islands in the Pacific, to provide a couple of international examples. The direct climate risks to the United Kingdom are also well known and include the increasing risks of flooding, extreme heat and coastal erosion. The winter floods of 2013/14, for instance, caused an estimated £450 million in insured losses.

The scientific consensus is that the main cause of human-induced climate change is the cumulative total emissions of CO₂ (as well as non-CO₂ greenhouse gases (GHG), particularly those with long lifetimes, such as nitrous oxide) (see, for example, Committee on Climate Change, Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, May 2019, pp 58-59).

Climate change seems now to be at the forefront of many agendas – personal, political and commercial. For instance:

Whilst there is growing political will across the sectors to combat climate change, what legal mechanisms are in place in the UK to ensure that substantive change actually occurs?

The UK has ratified a number of international treaties, including the Paris Agreement, which was adopted at the 21st conference of parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015. That agreement contains a long-term temperature goal of ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°c above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°c above pre-industrial levels’ (see Article 2(1)(a)). One way identified to reach that goal is to ‘reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible’ (Article 4(1)). Given our dualist legal system, the international treaties alone do not create obligations enforceable domestically.

The Climate Change Act 2008 (CCA 2008) is the principal legislation, which was enacted, in part, to make the reduction of GHG emissions legally binding and to provide for a system of carbon budgeting. The Act applies to the whole of the UK (but there are certain exceptions – see CCA 2008, s 99).

Regarding the reduction of GHG emissions, s 1 of the CCA 2008 was amended in June 2019 to place a statutory duty on the Secretary of State to ensure that the ‘net UK carbon account’ for the year 2050 is at least 100% lower than the 1990 baseline. Where the ‘1990 baseline’ is defined as the aggregate amount of both:

The UK government claims that this constitutes the ‘legally binding target of net zero emissions by 2050’ (which is the wording from a press statement dated 27 June 2019 on the gov.uk website).

The ‘net UK carbon account’ for a period means the net UK emissions of a targeted GHG for the relevant period that is reduced or increased by the carbon units respectively credited or debited to the account for the period (CCA 2008, s 27).

A ‘carbon unit’ is a unit defined by the Secretary of State, which represents either:

Pursuant to s 11, the Secretary of State is required to set a limit on the net amount of carbon units that may be credited to the net UK carbon account for each budgetary period. It also, however, empowers the Secretary of State to specify that carbon units of a particular description do not count towards the limit.

The Secretary of State has set the limit at 55,000,000 carbon units for 2018-2022, but at the same time, excluded those carbon units credited or debited under the scheme for GHG allowance trading established under the Emissions Trading Directive (‘EU ETS’, The Climate Change Act 2008 (Credit Limit) Order 2016 No.786).

The EU ETS is described by the UK government as the ‘largest multi-country, multi-sector greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme in the world’. The scheme covers 11,000 power stations and industrial plants of which 1,000 are based in the UK, which includes oil refineries, offshore platforms and industries that produce iron and steel, cement and lime, paper, glass ceramics and chemicals – seemingly those industries that would contribute most to GHG emissions.

Moreover, s 30 of CCA 2008 expressly excludes GHG emissions from international aviation and international shipping. This exclusion not only means that the impacts of international supply chains cannot be adequately accounted for by the legal obligations within the CCA 2008, but the provision also empowers the Secretary of State to define those terms at his or her discretion. The definition of ‘international aviation’ is broad enough to include those flights that have one or more interim stops in the UK (see Climate Change Act 2008 (2020 Target, Credit Limit and Definitions) Order 2009/1258, Article 4(2)).

Overall, the CCA 2008 places a statutory duty on the Secretary of State to reach net zero emissions by 2050 – a breach of which could be challenged by even anticipatory judicial review proceedings. The effectiveness of such proceedings in certain circumstances should not be understated (see the ClientEarth litigation on air quality). Yet, the Act also:

Readers of Counsel do not need to be told about the impact of climate change – our festive periods were coloured by the numerous reports and images of the deadly wildfires in Australia; and the rising sea level is an immediate existential threat for those living on islands in the Pacific, to provide a couple of international examples. The direct climate risks to the United Kingdom are also well known and include the increasing risks of flooding, extreme heat and coastal erosion. The winter floods of 2013/14, for instance, caused an estimated £450 million in insured losses.

The scientific consensus is that the main cause of human-induced climate change is the cumulative total emissions of CO₂ (as well as non-CO₂ greenhouse gases (GHG), particularly those with long lifetimes, such as nitrous oxide) (see, for example, Committee on Climate Change, Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, May 2019, pp 58-59).

Climate change seems now to be at the forefront of many agendas – personal, political and commercial. For instance:

Whilst there is growing political will across the sectors to combat climate change, what legal mechanisms are in place in the UK to ensure that substantive change actually occurs?

The UK has ratified a number of international treaties, including the Paris Agreement, which was adopted at the 21st conference of parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015. That agreement contains a long-term temperature goal of ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°c above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°c above pre-industrial levels’ (see Article 2(1)(a)). One way identified to reach that goal is to ‘reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible’ (Article 4(1)). Given our dualist legal system, the international treaties alone do not create obligations enforceable domestically.

The Climate Change Act 2008 (CCA 2008) is the principal legislation, which was enacted, in part, to make the reduction of GHG emissions legally binding and to provide for a system of carbon budgeting. The Act applies to the whole of the UK (but there are certain exceptions – see CCA 2008, s 99).

Regarding the reduction of GHG emissions, s 1 of the CCA 2008 was amended in June 2019 to place a statutory duty on the Secretary of State to ensure that the ‘net UK carbon account’ for the year 2050 is at least 100% lower than the 1990 baseline. Where the ‘1990 baseline’ is defined as the aggregate amount of both:

The UK government claims that this constitutes the ‘legally binding target of net zero emissions by 2050’ (which is the wording from a press statement dated 27 June 2019 on the gov.uk website).

The ‘net UK carbon account’ for a period means the net UK emissions of a targeted GHG for the relevant period that is reduced or increased by the carbon units respectively credited or debited to the account for the period (CCA 2008, s 27).

A ‘carbon unit’ is a unit defined by the Secretary of State, which represents either:

Pursuant to s 11, the Secretary of State is required to set a limit on the net amount of carbon units that may be credited to the net UK carbon account for each budgetary period. It also, however, empowers the Secretary of State to specify that carbon units of a particular description do not count towards the limit.

The Secretary of State has set the limit at 55,000,000 carbon units for 2018-2022, but at the same time, excluded those carbon units credited or debited under the scheme for GHG allowance trading established under the Emissions Trading Directive (‘EU ETS’, The Climate Change Act 2008 (Credit Limit) Order 2016 No.786).

The EU ETS is described by the UK government as the ‘largest multi-country, multi-sector greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme in the world’. The scheme covers 11,000 power stations and industrial plants of which 1,000 are based in the UK, which includes oil refineries, offshore platforms and industries that produce iron and steel, cement and lime, paper, glass ceramics and chemicals – seemingly those industries that would contribute most to GHG emissions.

Moreover, s 30 of CCA 2008 expressly excludes GHG emissions from international aviation and international shipping. This exclusion not only means that the impacts of international supply chains cannot be adequately accounted for by the legal obligations within the CCA 2008, but the provision also empowers the Secretary of State to define those terms at his or her discretion. The definition of ‘international aviation’ is broad enough to include those flights that have one or more interim stops in the UK (see Climate Change Act 2008 (2020 Target, Credit Limit and Definitions) Order 2009/1258, Article 4(2)).

Overall, the CCA 2008 places a statutory duty on the Secretary of State to reach net zero emissions by 2050 – a breach of which could be challenged by even anticipatory judicial review proceedings. The effectiveness of such proceedings in certain circumstances should not be understated (see the ClientEarth litigation on air quality). Yet, the Act also:

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court