*/

A media storm followed the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler. Ali Naseem Bajwa QC examines the fallout from the case

A media storm followed the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler. Ali Naseem Bajwa QC examines the fallout from the case

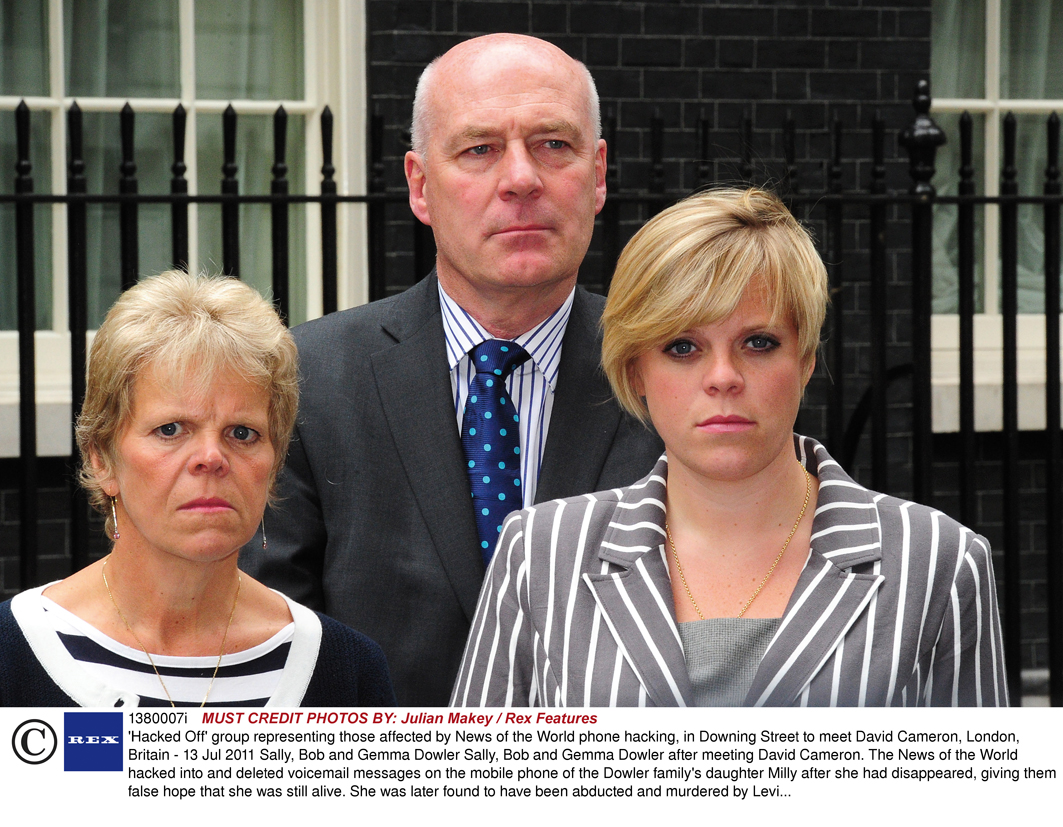

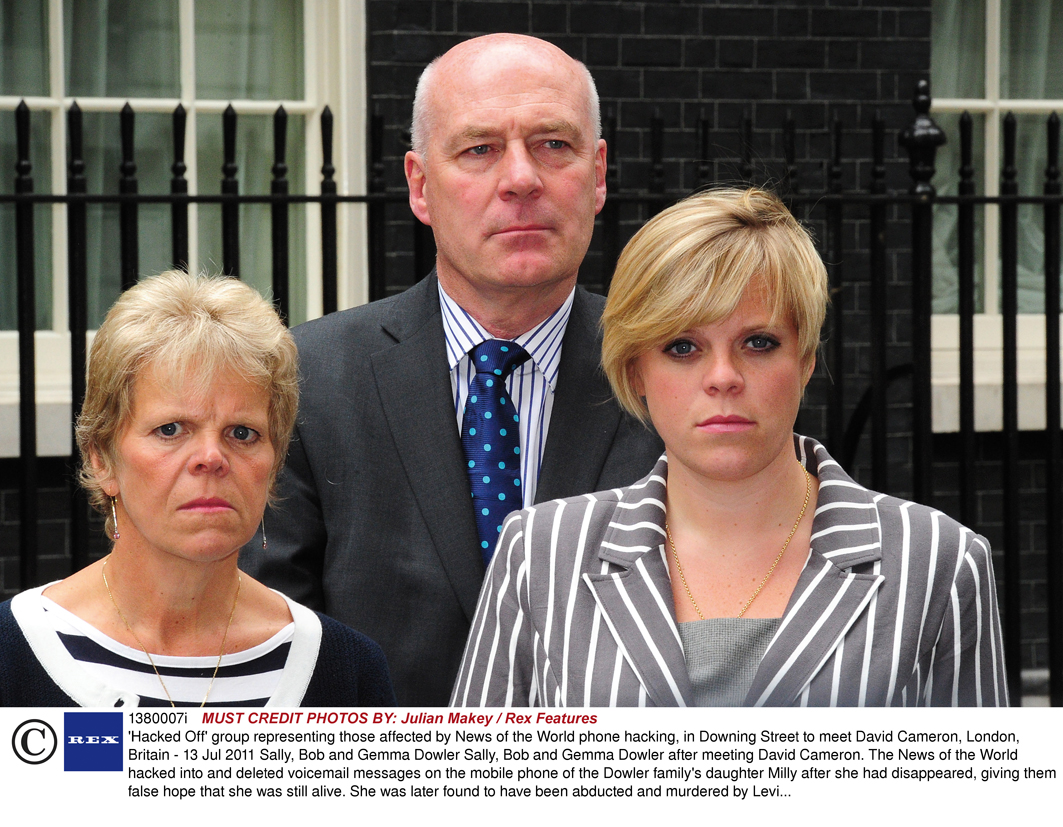

The medieval practice of determining guilt or innocence by subjecting the accused to trial by ordeal has happily long since passed. However, following the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler, the victim’s family described their experience of the trial as an ordeal and said that they had paid “too high a price” for the conviction. In the ensuing media and, inevitable, political storm the Criminal Justice System came in for intense criticism, much of it centred on a claim that the trial process is balanced unfairly in favour of the rights of the accused over the rights of victims of crime and witnesses.

Are victims and witnesses now exposed to a modern-day trial by ordeal and if so, what, if anything, should be done about it?

On 21 March 2002, 13-year-old Amanda “Milly” Dowler left school to take a train home but diverted to the station café with friends. After telephoning her father to say she would be home in half an hour, she left the café on foot. Milly was last seen walking along a main road in the direction of her home in Walton-on-Thames in Surrey. She never arrived. That evening, her parents reported her missing to the police and there followed a nationwide missing person search. At first the police enquiry focused on whether Milly may have run away but as the weeks and months passed, fears grew that she had been killed. Six months after her disappearance, the worst fears were confirmed as Milly’s decomposed remains were discovered in Yateley Heath Woods in Hampshire.

Levi Bellfield’s trial for the kidnap and murder of Milly began at the Central Criminal Court before Mr Justice Wilkie and a jury on 10 May this year. The Crown had a strong circumstantial case, including evidence that Bellfield: occupied a flat within metres of the spot that Milly was last seen alive; attempted to kidnap a young woman the day before Milly was last seen alive; and, in the two years thereafter, in circumstances which bore a striking similarity to Milly’s disappearance, abducted and murdered two young women and attempted to murder a third.

The issues boiled down to this: if Bellfield was not responsible for Milly’s murder, there were really only two other possibilities: either

a person other than him, with a freakishly similar opportunity and skill at abducting and killing young women, had kidnapped and murdered Milly; or

Milly had not been abducted by Bellfield at a location just metres from his flat but had chosen to run away from home, and had met her death in an unknown way and at an unknown place not long thereafter.

Given Bellfield’s plea of not guilty and the extreme unlikelihood of the first possibility, the defence had little choice but to pursue the second one.

In order to persuade the jury that Milly may have run away, the defence cross-examined members of the Dowler family about highly personal and sensitive material which suggested that, many months before her disappearance, Milly did not enjoy a good relationship with her parents, was unhappy at home and had considered running away. Unsurprisingly, the witnesses found the cross-examination deeply distressing and hurtful – Milly’s mother broke down as she left the witness box and her father was in tears during a good deal of his evidence.

In reality, there was nothing either the Crown or the court could have done to prevent the cross-examination. First, the Crown had no choice but to call Milly’s parents and uncle to give evidence; each of them had important evidence of fact to give (although, to its credit, the Crown spared Milly’s sister that anguish by abandoning her as a live witness and, with the agreement of the defence, reading her statement to the court). Second, none of the material introduced by the defence amounted to evidence of “bad character” (defined as “evidence of, or a disposition towards, misconduct”), for which the judge’s leave was required.

Third, the cross-examination was relevant to an issue in the case, namely whether Milly had been abducted or had run away. It is right to say that the evidence of Milly having run away was tenuous and weak; however it was not so weak as to prohibit it being introduced at all. Its strength or weakness, particularly given the burden and high standard of proof in a criminal trial, was a matter for the jury to determine.

It seems clear that no changes to the trial process should be made to prevent this or any other relevant line of cross-examination. Moreover, whilst every criticism can be made of Bellfield, no criticism can be made of Bellfield’s counsel for having introduced the material. Counsel was right, indeed was obliged, to explore an alternative version of events which was based on his instructions, supported by evidence and relevant to his client’s defence. Some parties have complained that the cross-examination was overly aggressive. However by all accounts it was firm but fair. Neither the Crown nor the judge intervened on the basis that the manner of cross-examination was improper. Indeed, in his sentencing remarks, the judge described it as “skilfully and sensitively” done.

It is all too easy to overlook the great strides that have been made in the Criminal Justice System in protecting the needs and rights of victims of crime and witnesses. A far from comprehensive list of these would include special measures directions, witness anonymity orders, the bad character provisions, reporting restrictions on the identity of victims of sexual offences, young persons and adults in fear or distress, increased powers to admit hearsay evidence, restrictions on cross-examination about a complainant’s sexual behaviour and the use of victim impact statements. The work of the Witness Care Unit and Victim Support is also invaluable in this regard.

Regrettably, the media in the Dowler trial gave a massive amount of publicity to the material introduced by the defence in cross-examination. Doing its best for the family, the Crown sought a reporting restriction in respect of the more personal aspects of it. However the application was, quite properly, refused on the basis there is insufficient power within the legislation or common law to make the order. Of course, the media did not have to report the highly personal material; they could have exercised self-censorship and declined to publish. Ironically, and somewhat hypocritically, the same sections of the media now complain at defence insensitivity to the Dowler family’s distress and loss of reputation.

There is here scope for change: a respectable argument can be made for extending the law, which already permits a court to postpone publication of false and derogatory mitigation, to restrict reporting of evidence in a trial which would have such a deleterious effect on the reputation of a witness that the reporting of it would affect the quality of a witness’s evidence and/or deter witnesses from coming forward in the future. The interests of open justice would militate in favour of the power being exercised sparingly and only in the most exceptional cases, of which the Dowler case might have been one.

Following the Milly Dowler trial, the Victim’s Commissioner, Louise Casey, issued her Review into the Needs of Families Bereaved by Homicide, in which she made a number of recommendations for bereaved families’ rights in the Criminal Justice System, including the early release of a victim’s body for burial, police updates at each stage of an investigation, the right to information from and meetings at key stages with the CPS, the introduction of a Criminal Procedure Direction about the needs and treatment of bereaved families in court and an integrated package of help and support following the death and beyond any trial. Many of these recommendations are very welcome.

As part of his response to the Casey review, the DPP, Keir Starmer QC, announced that the CPS was enhancing its service to bereaved families by offering face-to-face meetings at a number of additional stages of the criminal process, including following an acquittal and the granting of leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

There is no question that the distress of and inconvenience to victims and witnesses must, as far as is practicably possible, be alleviated. Ultimately however, there is a limit on the extent to which the trial process or the rules of evidence can be changed to protect victims and witnesses and it is misguided to contend for a Criminal Justice System which “balances” the rights of the accused against the rights of victims and witnesses. Unlike the accused, a victim or witness does not face the risk of criminal conviction and imprisonment. For this reason, the accused person’s right to a fair trial is paramount and cannot be compromised.

It is possible both to feel profound sympathy for the Dowler family, who in the course of Bellfield’s trial had indignity heaped upon an unimaginable tragedy, and at the same time to believe that no radical changes need to be made to the Criminal Justice System.

Nine years on from Milly’s disappearance, Levi Bellfield was convicted of her kidnap and murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order. The evidence was thoroughly examined, the jury came to a verdict which necessarily rejected the alternative defence version (thereby vindicating the Dowlers), and a richly deserved sentence followed. In the final analysis, however arduous the journey for the family, justice was done.

Ali Naseem Bajwa QC, Garden Court Chambers

Are victims and witnesses now exposed to a modern-day trial by ordeal and if so, what, if anything, should be done about it?

On 21 March 2002, 13-year-old Amanda “Milly” Dowler left school to take a train home but diverted to the station café with friends. After telephoning her father to say she would be home in half an hour, she left the café on foot. Milly was last seen walking along a main road in the direction of her home in Walton-on-Thames in Surrey. She never arrived. That evening, her parents reported her missing to the police and there followed a nationwide missing person search. At first the police enquiry focused on whether Milly may have run away but as the weeks and months passed, fears grew that she had been killed. Six months after her disappearance, the worst fears were confirmed as Milly’s decomposed remains were discovered in Yateley Heath Woods in Hampshire.

Levi Bellfield’s trial for the kidnap and murder of Milly began at the Central Criminal Court before Mr Justice Wilkie and a jury on 10 May this year. The Crown had a strong circumstantial case, including evidence that Bellfield: occupied a flat within metres of the spot that Milly was last seen alive; attempted to kidnap a young woman the day before Milly was last seen alive; and, in the two years thereafter, in circumstances which bore a striking similarity to Milly’s disappearance, abducted and murdered two young women and attempted to murder a third.

The issues boiled down to this: if Bellfield was not responsible for Milly’s murder, there were really only two other possibilities: either

a person other than him, with a freakishly similar opportunity and skill at abducting and killing young women, had kidnapped and murdered Milly; or

Milly had not been abducted by Bellfield at a location just metres from his flat but had chosen to run away from home, and had met her death in an unknown way and at an unknown place not long thereafter.

Given Bellfield’s plea of not guilty and the extreme unlikelihood of the first possibility, the defence had little choice but to pursue the second one.

In order to persuade the jury that Milly may have run away, the defence cross-examined members of the Dowler family about highly personal and sensitive material which suggested that, many months before her disappearance, Milly did not enjoy a good relationship with her parents, was unhappy at home and had considered running away. Unsurprisingly, the witnesses found the cross-examination deeply distressing and hurtful – Milly’s mother broke down as she left the witness box and her father was in tears during a good deal of his evidence.

In reality, there was nothing either the Crown or the court could have done to prevent the cross-examination. First, the Crown had no choice but to call Milly’s parents and uncle to give evidence; each of them had important evidence of fact to give (although, to its credit, the Crown spared Milly’s sister that anguish by abandoning her as a live witness and, with the agreement of the defence, reading her statement to the court). Second, none of the material introduced by the defence amounted to evidence of “bad character” (defined as “evidence of, or a disposition towards, misconduct”), for which the judge’s leave was required.

Third, the cross-examination was relevant to an issue in the case, namely whether Milly had been abducted or had run away. It is right to say that the evidence of Milly having run away was tenuous and weak; however it was not so weak as to prohibit it being introduced at all. Its strength or weakness, particularly given the burden and high standard of proof in a criminal trial, was a matter for the jury to determine.

It seems clear that no changes to the trial process should be made to prevent this or any other relevant line of cross-examination. Moreover, whilst every criticism can be made of Bellfield, no criticism can be made of Bellfield’s counsel for having introduced the material. Counsel was right, indeed was obliged, to explore an alternative version of events which was based on his instructions, supported by evidence and relevant to his client’s defence. Some parties have complained that the cross-examination was overly aggressive. However by all accounts it was firm but fair. Neither the Crown nor the judge intervened on the basis that the manner of cross-examination was improper. Indeed, in his sentencing remarks, the judge described it as “skilfully and sensitively” done.

It is all too easy to overlook the great strides that have been made in the Criminal Justice System in protecting the needs and rights of victims of crime and witnesses. A far from comprehensive list of these would include special measures directions, witness anonymity orders, the bad character provisions, reporting restrictions on the identity of victims of sexual offences, young persons and adults in fear or distress, increased powers to admit hearsay evidence, restrictions on cross-examination about a complainant’s sexual behaviour and the use of victim impact statements. The work of the Witness Care Unit and Victim Support is also invaluable in this regard.

Regrettably, the media in the Dowler trial gave a massive amount of publicity to the material introduced by the defence in cross-examination. Doing its best for the family, the Crown sought a reporting restriction in respect of the more personal aspects of it. However the application was, quite properly, refused on the basis there is insufficient power within the legislation or common law to make the order. Of course, the media did not have to report the highly personal material; they could have exercised self-censorship and declined to publish. Ironically, and somewhat hypocritically, the same sections of the media now complain at defence insensitivity to the Dowler family’s distress and loss of reputation.

There is here scope for change: a respectable argument can be made for extending the law, which already permits a court to postpone publication of false and derogatory mitigation, to restrict reporting of evidence in a trial which would have such a deleterious effect on the reputation of a witness that the reporting of it would affect the quality of a witness’s evidence and/or deter witnesses from coming forward in the future. The interests of open justice would militate in favour of the power being exercised sparingly and only in the most exceptional cases, of which the Dowler case might have been one.

Following the Milly Dowler trial, the Victim’s Commissioner, Louise Casey, issued her Review into the Needs of Families Bereaved by Homicide, in which she made a number of recommendations for bereaved families’ rights in the Criminal Justice System, including the early release of a victim’s body for burial, police updates at each stage of an investigation, the right to information from and meetings at key stages with the CPS, the introduction of a Criminal Procedure Direction about the needs and treatment of bereaved families in court and an integrated package of help and support following the death and beyond any trial. Many of these recommendations are very welcome.

As part of his response to the Casey review, the DPP, Keir Starmer QC, announced that the CPS was enhancing its service to bereaved families by offering face-to-face meetings at a number of additional stages of the criminal process, including following an acquittal and the granting of leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

There is no question that the distress of and inconvenience to victims and witnesses must, as far as is practicably possible, be alleviated. Ultimately however, there is a limit on the extent to which the trial process or the rules of evidence can be changed to protect victims and witnesses and it is misguided to contend for a Criminal Justice System which “balances” the rights of the accused against the rights of victims and witnesses. Unlike the accused, a victim or witness does not face the risk of criminal conviction and imprisonment. For this reason, the accused person’s right to a fair trial is paramount and cannot be compromised.

It is possible both to feel profound sympathy for the Dowler family, who in the course of Bellfield’s trial had indignity heaped upon an unimaginable tragedy, and at the same time to believe that no radical changes need to be made to the Criminal Justice System.

Nine years on from Milly’s disappearance, Levi Bellfield was convicted of her kidnap and murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order. The evidence was thoroughly examined, the jury came to a verdict which necessarily rejected the alternative defence version (thereby vindicating the Dowlers), and a richly deserved sentence followed. In the final analysis, however arduous the journey for the family, justice was done.

Ali Naseem Bajwa QC, Garden Court Chambers

A media storm followed the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler. Ali Naseem Bajwa QC examines the fallout from the case

A media storm followed the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler. Ali Naseem Bajwa QC examines the fallout from the case

The medieval practice of determining guilt or innocence by subjecting the accused to trial by ordeal has happily long since passed. However, following the conviction of Levi Bellfield for the murder of Milly Dowler, the victim’s family described their experience of the trial as an ordeal and said that they had paid “too high a price” for the conviction. In the ensuing media and, inevitable, political storm the Criminal Justice System came in for intense criticism, much of it centred on a claim that the trial process is balanced unfairly in favour of the rights of the accused over the rights of victims of crime and witnesses.

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier

Patrick Green KC talks about the landmark Post Office Group litigation and his driving principles for life and practice. Interview by Anthony Inglese CB

Desiree Artesi meets Malcolm Bishop KC, the Lord Chief Justice of Tonga, who talks about his new role in the South Pacific and reflects on his career