*/

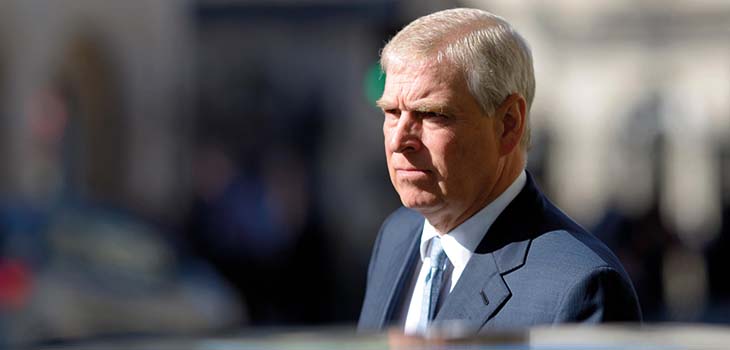

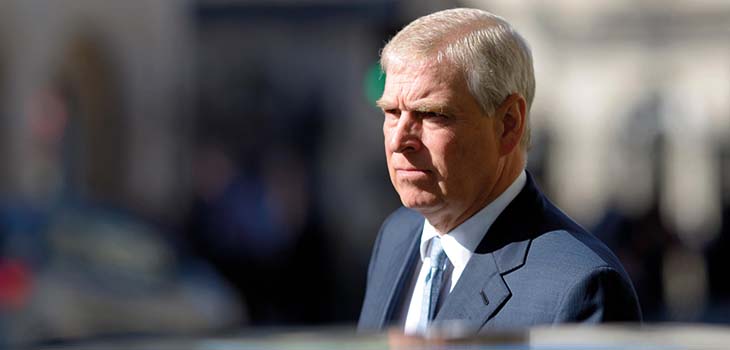

On 10 March 2022, Prince Andrew was scheduled to sit for a deposition in a civil case filed by Virginia Giuffre, and he wisely chose to settle before doing so. The date is significant to the case for other reasons. It marks 21 years to the day when Giuffre says she was sexually trafficked for the first of three times to Prince Andrew in the Belgravia home of British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell. It is the date Giuffre attributed to the now infamous photograph showing her, at 17 years old, with Prince Andrew and Maxwell. The image was included in a complaint filed against Prince Andrew in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York alleging sexual abuse.

In his 2019 BBC Newsnight interview with Emily Maitlis, broadcast before Giuffre’s claim was filed in 2020, the Prince responded that on 10 March 2001 he had taken his daughter to a Pizza Express in Woking ‘for a party at, I suppose, sort of 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon.’

If Prince Andrew’s interview – conducted in the comfortable and familiar surroundings of Buckingham Palace – gives an indication of how he would have responded in a formal deposition taken under oath, he and his lawyers most certainly had reason to be worried. While he says he could not recall ever meeting Giuffre, the Prince maintained that he is sure about where he was on this particular day in March, two decades ago.

At the time of the interview, commentators described Andrew’s performance as a ‘car crash’ in public relations terms. Looking back now, we might see it as a car crash, followed by a train wreck, and then by an explosion. Andrew’s statements locked him into a narrative that was indefensible in the lawsuit. His narrative was not one his lawyers would have wanted to place in the hands of jurors.

In the interview, Andrew expressed no regret for his relationship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein because of ‘the people that I met and the opportunities that I was given to learn’. Andrew told us he was not capable of sweating at that time as Giuffre claimed he had done at the Tramp Nightclub the evening of the alleged assault because of a ‘peculiar medical condition’. Who doesn’t sweat? He also told us that he does not hug as the photo purports him to do. Who doesn’t hug? Soon, the media showed us images from online sources showing the Prince hugging, sweating, and, yes, even out without a tie and jacket, which he claimed he did not do. If the jury could not rely on Andrew’s account concerning minute details, how could the jury rely on his account concerning the ultimate issue?

Asked in interview why he visited Epstein after knowing Epstein was a convicted sex offender, the Prince stated that he wanted to tell him in person that they could not be seen together any longer. Pressed on why this had to be done in person and over a period of four days, Andrew offered an incredulous rationale that ‘my judgement was probably coloured by my tendency to be too honourable’. The worst part of the interview was not what he said, but what he didn’t say. He expressed no sympathy for Giuffre or any of Jeffrey Epstein’s many other victims.

After Judge Lewis Kaplan denied the Prince’s Motion to Dismiss on procedural grounds, Prince Andrew then faced two undesirable options – settle the case out of court or continue ahead with a trial on the merits. Andrew refused to settle the case before it was filed, and continued to refuse settlement as the date approached for his deposition. As he did so, the price tag attached to this refusal increased. His accumulated losses included reputation, royal duties, titles, charities, memberships and countless other privileges that come from being son to the longest reigning monarch in British history.

Even for a son of privilege, actions have consequences. The rising cost paid by Prince Andrew for prolonging litigation is a consequence of the same poor decision-making he exercised in sitting for the BBC interview, not to mention the performance itself. At a time when the nation celebrates Queen Elizabeth II’s unprecedented Platinum Jubilee year, her second son was doubling down on his refusal to settle when he asked for his day in court. The case cost him everything.

Andrew was hoping that Giuffre’s case lived merely to die another day when he could re-litigate a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule 12(b)(6) for ‘failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted’. One of his principal arguments concerned federal subject matter jurisdiction. Seeking to continue with the case in the hope of eventual dismissal on procedural grounds came with great risk that the Prince seems only now to fully appreciate.

To obtain discovery from Giuffre, the Prince would have had to subject himself to deposition – the most effective discovery tool in the arsenal of civil litigants. A deposition is a sit-down interview allowing a party to test a witness’s credibility. In the context of a deposition, privilege can be a major disadvantage to a witness. Due to his status, Prince Andrew is not a person who is routinely questioned about much of anything, and his interview showcases an inability to respond to probing questions with answers that are credible and easily corroborated.

The Duke seems to have understood that the risk of being deposed was one not to take lightly. It would take only a simple majority among 16-23 New Yorkers with (Grand) Jury Duty to indict him on perjury if he lies under oath. Avoiding even the possibility of criminal charges has value, but the Prince was only able to avoid this risk when he settled out of court prior to giving his deposition.

I do not suggest that Prince Andrew is guilty of the conduct alleged. I do suggest that his interview performance helped Giuffre’s claims appear more reasonable than they would have standing on their own, especially considering that the standard of proof required in civil cases is quite low. The preponderance of the evidence standard is akin to the balance of probabilities test in English law. Jurors would have been asked to decide whether it was ‘more likely than not’ that Giuffre’s allegations were true. Jurors could have had a reasonable doubt and still found Andrew liable since the standard of proof is lower than the standard of proof in criminal cases which requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Attorney David Bois would have had a field day, or in Royal parlance, a ‘straightforward shooting weekend’, if he had questioned the Prince on the treasure trove of statements Andrew volunteered in his 2019 interview. The Prince would have had to either repeat that same narrative or disclaim what he said earlier; neither of which bespeaks credibility. He could not have asserted his Fifth Amendment right to silence either, at least not without inviting an instruction permitting jurors to draw an adverse inference from that silence.

Prince Andrew was not similarly situated to other defendants and, in that sense, he could not have received the same type of trial others would have. Giuffre’s account is one that jurors would have found more relatable. The Prince was right to avoid facing judgment by 12 angry men and women, many with daughters and granddaughters, in the era of the #MeToo Movement.

Andrew had already lost his case in the court of public opinion. His ongoing fight to ‘clear his name’ was not one he could win. He opted, instead, to lose the least. Settling the claim out of court, and before sitting for the deposition, was the only way to do this – though it carried the implication of liability, it avoided any risk of criminal liability and the appearance of having walked on a procedural technicality. Settlement was also, perhaps, consistent with a ‘tendency to be too honourable’.

In January 2022, John J Burke was the featured speaker at a public forum hosted by Legis Chambers called 'The Case Against Prince Andrew: An American Perspective' in which he advised that Prince Andrew settle the claim.

On 10 March 2022, Prince Andrew was scheduled to sit for a deposition in a civil case filed by Virginia Giuffre, and he wisely chose to settle before doing so. The date is significant to the case for other reasons. It marks 21 years to the day when Giuffre says she was sexually trafficked for the first of three times to Prince Andrew in the Belgravia home of British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell. It is the date Giuffre attributed to the now infamous photograph showing her, at 17 years old, with Prince Andrew and Maxwell. The image was included in a complaint filed against Prince Andrew in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York alleging sexual abuse.

In his 2019 BBC Newsnight interview with Emily Maitlis, broadcast before Giuffre’s claim was filed in 2020, the Prince responded that on 10 March 2001 he had taken his daughter to a Pizza Express in Woking ‘for a party at, I suppose, sort of 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon.’

If Prince Andrew’s interview – conducted in the comfortable and familiar surroundings of Buckingham Palace – gives an indication of how he would have responded in a formal deposition taken under oath, he and his lawyers most certainly had reason to be worried. While he says he could not recall ever meeting Giuffre, the Prince maintained that he is sure about where he was on this particular day in March, two decades ago.

At the time of the interview, commentators described Andrew’s performance as a ‘car crash’ in public relations terms. Looking back now, we might see it as a car crash, followed by a train wreck, and then by an explosion. Andrew’s statements locked him into a narrative that was indefensible in the lawsuit. His narrative was not one his lawyers would have wanted to place in the hands of jurors.

In the interview, Andrew expressed no regret for his relationship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein because of ‘the people that I met and the opportunities that I was given to learn’. Andrew told us he was not capable of sweating at that time as Giuffre claimed he had done at the Tramp Nightclub the evening of the alleged assault because of a ‘peculiar medical condition’. Who doesn’t sweat? He also told us that he does not hug as the photo purports him to do. Who doesn’t hug? Soon, the media showed us images from online sources showing the Prince hugging, sweating, and, yes, even out without a tie and jacket, which he claimed he did not do. If the jury could not rely on Andrew’s account concerning minute details, how could the jury rely on his account concerning the ultimate issue?

Asked in interview why he visited Epstein after knowing Epstein was a convicted sex offender, the Prince stated that he wanted to tell him in person that they could not be seen together any longer. Pressed on why this had to be done in person and over a period of four days, Andrew offered an incredulous rationale that ‘my judgement was probably coloured by my tendency to be too honourable’. The worst part of the interview was not what he said, but what he didn’t say. He expressed no sympathy for Giuffre or any of Jeffrey Epstein’s many other victims.

After Judge Lewis Kaplan denied the Prince’s Motion to Dismiss on procedural grounds, Prince Andrew then faced two undesirable options – settle the case out of court or continue ahead with a trial on the merits. Andrew refused to settle the case before it was filed, and continued to refuse settlement as the date approached for his deposition. As he did so, the price tag attached to this refusal increased. His accumulated losses included reputation, royal duties, titles, charities, memberships and countless other privileges that come from being son to the longest reigning monarch in British history.

Even for a son of privilege, actions have consequences. The rising cost paid by Prince Andrew for prolonging litigation is a consequence of the same poor decision-making he exercised in sitting for the BBC interview, not to mention the performance itself. At a time when the nation celebrates Queen Elizabeth II’s unprecedented Platinum Jubilee year, her second son was doubling down on his refusal to settle when he asked for his day in court. The case cost him everything.

Andrew was hoping that Giuffre’s case lived merely to die another day when he could re-litigate a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule 12(b)(6) for ‘failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted’. One of his principal arguments concerned federal subject matter jurisdiction. Seeking to continue with the case in the hope of eventual dismissal on procedural grounds came with great risk that the Prince seems only now to fully appreciate.

To obtain discovery from Giuffre, the Prince would have had to subject himself to deposition – the most effective discovery tool in the arsenal of civil litigants. A deposition is a sit-down interview allowing a party to test a witness’s credibility. In the context of a deposition, privilege can be a major disadvantage to a witness. Due to his status, Prince Andrew is not a person who is routinely questioned about much of anything, and his interview showcases an inability to respond to probing questions with answers that are credible and easily corroborated.

The Duke seems to have understood that the risk of being deposed was one not to take lightly. It would take only a simple majority among 16-23 New Yorkers with (Grand) Jury Duty to indict him on perjury if he lies under oath. Avoiding even the possibility of criminal charges has value, but the Prince was only able to avoid this risk when he settled out of court prior to giving his deposition.

I do not suggest that Prince Andrew is guilty of the conduct alleged. I do suggest that his interview performance helped Giuffre’s claims appear more reasonable than they would have standing on their own, especially considering that the standard of proof required in civil cases is quite low. The preponderance of the evidence standard is akin to the balance of probabilities test in English law. Jurors would have been asked to decide whether it was ‘more likely than not’ that Giuffre’s allegations were true. Jurors could have had a reasonable doubt and still found Andrew liable since the standard of proof is lower than the standard of proof in criminal cases which requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Attorney David Bois would have had a field day, or in Royal parlance, a ‘straightforward shooting weekend’, if he had questioned the Prince on the treasure trove of statements Andrew volunteered in his 2019 interview. The Prince would have had to either repeat that same narrative or disclaim what he said earlier; neither of which bespeaks credibility. He could not have asserted his Fifth Amendment right to silence either, at least not without inviting an instruction permitting jurors to draw an adverse inference from that silence.

Prince Andrew was not similarly situated to other defendants and, in that sense, he could not have received the same type of trial others would have. Giuffre’s account is one that jurors would have found more relatable. The Prince was right to avoid facing judgment by 12 angry men and women, many with daughters and granddaughters, in the era of the #MeToo Movement.

Andrew had already lost his case in the court of public opinion. His ongoing fight to ‘clear his name’ was not one he could win. He opted, instead, to lose the least. Settling the claim out of court, and before sitting for the deposition, was the only way to do this – though it carried the implication of liability, it avoided any risk of criminal liability and the appearance of having walked on a procedural technicality. Settlement was also, perhaps, consistent with a ‘tendency to be too honourable’.

In January 2022, John J Burke was the featured speaker at a public forum hosted by Legis Chambers called 'The Case Against Prince Andrew: An American Perspective' in which he advised that Prince Andrew settle the claim.

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier