*/

.jpg?sfvrsn=1759a295_1)

Since 2018 I have analysed and reported on data showing the significant work and pay imbalance between the sexes at the self-employed publicly funded Bar, focusing first on the criminal Bar, and latterly including the Government Legal Department (GLD) which administers the panels on behalf of the Attorney General.

The figures I reported pre-pandemic were sufficiently stark to cause both the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the GLD to undertake their own internal reviews, which in turn led to the CPS implementing policies and procedures to record, retain and analyse their respective briefing patterns to avoid inequity, and the GLD stating that it would follow suit.

The Bar Council also transformed its own recording and reporting, and began publishing detailed reports on receipts by gender and ethnicity through analysing the practising certificate declarations that all self-employed barristers are required annually to submit to the Bar Mutual Indemnity Fund (BMIF). Its first such report, published in 2020, corresponded with my analyses of publicly funded work allocation, and further demonstrated a very significant gender income gap in every area of practice and at every level of call, starting in the first year of practice and continuing into silk. There were some limitations – in particular the data analysis was impaired by the fact that BMIF does not collect monitoring data on barristers and therefore sex had to be inferred from prefixes. Barristers who did not supply a prefix, or used a gender neutral prefix such as Dr, were therefore excluded from the data analysis.

The Bar Council further refined its approach in its next detailed report, Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar, in November 2023. It based its analysis on its own data received from each member of the Bar when they renew their practising certificate, and thus was able more comprehensively to analyse by reference to sex and to practice area. Little if anything has changed post-pandemic; of most concern is the Bar Council’s finding that the disparity starts from day one of a barrister’s career. The Bar Council examined post-qualification years 0-3 more closely in an April 2024 report, New practitioner earnings differentials at the self-employed Bar. It looked at the three practice years to March 2024 and concluded that a gap of between 9% and 13% exists at every post-qualification year from 0-3, exists across every area of practice, and exists both among barristers who have caring responsibilities and among those who do not. Further, of those for whom legal aid work comprises at least three quarters of their earnings, women at 0-3 years’ PQE earn on average 13% less than their male counterparts. The report also found that where chambers give barristers regular practice reviews and have policies to ensure the fair allocation of led work, then earnings gaps are reduced.

I was subsequently asked by several senior female members of the Bar (criminal and civil practitioners) to look again at work allocation and receipts at the publicly funded Bar to see if any of the measures put in place since I started reporting were working. Anecdotally, they each felt that despite the various promised measures and recommendations, little had changed on the ground. This unease has been reflected in discussions between the Treasury Solicitor with the Administrative Law Bar Association, with the Inns of Court Alliance for Women and with female GLD panel counsel members, who have made clear their perception that high quality work is not available for women as they rise through the government panels.

The Bar Council November 2023 report gives foundation to this perception. It concluded that while men’s and women’s gross earnings had both slightly increased in year ending April 2023 (the first full practice year following the pandemic) the difference in gross earnings between men and women at all call levels and in all areas of practice has not narrowed. Further, the Bar Council’s latest report, published on 4 February 2025, shows a worsening situation: not only does the income gap between the sexes persist at every call level and in every practice area, but it is increasing. In the calendar year 2023 junior women at the self-employed Bar earned on average 77% of the earnings of their male colleagues; in silk the women earned on average 67% of their male colleague’s median earnings.

What then, can we learn from the allocation of publicly funded instructions? I again approached the criminal department of the Legal Aid Agency (LAA), the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the Attorney General’s Office and the Treasury Solicitor. I am grateful to all for sharing their data.

Key findings in my 2021 report on GLD instruction:

The GLD recorded ‘instructions’ not as individual cases, but as cases invoiced per quarter: if a barrister invoiced a single case four times per quarter, that was recorded as one instruction; if she invoiced on that same case once per quarter over a year, that was recorded as four instructions. This made it very difficult properly to understand how equitable or otherwise allocation of work was. At the time, the Attorney General’s Office told me: ‘Successive Law Officers have been keen to advance equality of opportunity between men and women at the Bar and the panels have been seen as a way of achieving this.’ However, it conceded that it did not keep central records relating to who was instructed, in which type of court or at what level, and had no centralised policy governing instructions save that the allocating lawyer instructing silks had to have regard to ‘encouraging diversity’. I was told: ‘Efforts are made to encourage applications [to the panels] from as wide a pool as possible and approaches are made to diversity groups including the Association of Women Barristers. Selection boards are comprised of men and women in equal numbers.’ Four years on, what is the result of those efforts?

Assessing equity of instruction via the GLD is still considerably hampered by the continued lack of any proper data monitoring within the Department. ‘Instructions’ remain recorded in the same way as in 2021. This is something Susanna McGibbon, Treasury Solicitor since 2021, frankly accepted. She was clear that she did not want to use the pandemic as an excuse, but nonetheless accepted that the progress hoped for when I last reported has not been made. Ms McGibbon told me: ‘As Treasury Solicitor I am very proud to lead a diverse department where women lawyers are overrepresented at every grade, and in contrast to the private sector, particularly so at the highest grades where the majority of legal directors and my three deputies are female. I am absolutely focused on ensuring the same diverse approach to the counsel we instruct, not just in gender but in all aspects of diversity so that the counsel who represent the government are more representative of the population as a whole. I have regularly discussed the diversity of the Civil Panel with the former and current Attorneys General, both of whom share an absolute commitment to the visible improvement in diversity in the counsel on their panels.

‘But I will be candid that we have not made as much progress as I would have liked, and there is more to do. I am committed to improving our instruction practice and supporting that with better data.

‘Historically our case management system has not been configured to record diversity data, so monitoring and reporting on diversity requires manual interrogation of our systems and searches on BAILII. In addition, our finance systems record numbers of “instructions” per quarter rather than individual cases or invoices, which makes it difficult to make accurate comparisons on instruction rates. We are making improvements to our current case management system to record diversity data about the panels in one place as well as tracking which counsel our lawyers are instructing. For the longer term, we are developing a new legal practice management system, and the ability to record and report on diversity of counsel instructed has been included in our requirements for the new system.’

While the ability to report and analyse gender patterns in GLD instructions consequently remains hampered, the Department was able to give me some useful data – in part by trawling BAILII – and I am grateful to it for undertaking this exercise, even if it is no real substitute for proper recording.

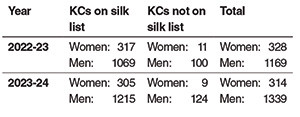

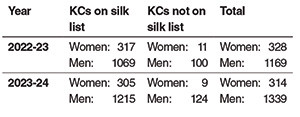

Data relating to King’s Counsel instructions from the GLD came in two categories – the KC list and non-list KCs. Ms McGibbon explained that there is no application process for KCs acting for government and therefore the KC list is simply a record of those who have previously worked for government or who have expressed an interest in doing so. As of June 2024, there were 450 silks on the KC list (civil and EU): 98 women (21.8%) and 352 men.

However, there is no requirement to be on the list for a KC to be instructed. This is reflected in the table below which sets out how many times male and female KCs have been instructed in the last 24 months:

We do not know the fiscal value of those instructions since the number of hours spent and billed is not monitored. From the information that has been supplied, we can see that:

One of the Bar Council 2023 report’s key findings was that women silks earn on average 71% of their male colleagues’ median gross earnings, which has since dropped to 67% according to the report published in February 2025. According to the Treasury Solicitor, the average hourly rate of male KCs instructed by government is currently £194; the average hourly rate for the female panel KCs is £187. Because of the lack of data monitoring there is no clear reason for this discrepancy. Ms McGibbon said: ‘The rate of £180 was effectively set in 2010 and has been largely frozen since that time, although a small number of KCs have successfully argued for a higher rate based on specialisms, particular experience and private sector comparators.’

It was only by reviewing BAILII that the GLD was able to tell me that in 2023 (calendar year), there were 17 KC appearances in the Supreme Court on behalf of the GLD, two of which were by women (12%) and that of 43 KC appearances in the Court of Appeal, eight were women (18.5%). There is foundation then, for the perception that women are not receiving the high-quality work as they move up the ranks. The new legal practice management system will hopefully allow for more accurate and helpful analysis based on income rather than ‘instructions’.

Turning to the junior Bar, the November 2023, April 2024 and February 2025 Bar Council reports conclude that men’s median gross earnings are higher than women’s in every call band and every area of practice. As already described, this significant gender gap begins at 0-3 years’ call where experience has much less bearing. 51% of barristers at this level are women; they account for 45% of the gross earnings. Therefore, men are better enabled to build their experience and portfolios right from the beginning of their careers. This is reflected in the gap between men’s and women’s median gross earnings by 11-15 years’ call. By this career stage 44% of barristers are women, but they receive only 34% of the gross earnings and earn on average 30% less than their male counterparts. At 16-20 years’ call 44% of barristers are women and they account for 33% of the gross earnings, earning 28% less than their male colleagues. Looking specifically at civil work, the Bar Council analysed the income of self-employed barristers declaring at least 80% of their income in one of the following four practice areas: family, commercial, Chancery and personal injury. Men significantly outearn women at every call stage in every area and dominate the highest earning practice areas: 79% of commercial barristers and 80% of Chancery specialists are men, and 90% of silks in both practice areas are men – and they significantly outearn the few women at every level.

On publicly funded civil work specifically, as part of the Review of Civil Legal Aid in 2023/24, the Bar Council created a dataset of eight years of legal aid payments to civil and family legal aid practitioners. Family work accounts for the majority of civil legal aid payments, with 73% of barristers in receipt of civil legal aid payments receiving them wholly for family work. In its formal Response to the Review’s call for evidence dated February 2024, the Bar Council stated: ‘Groups of advocates have different levels of reliance on civil legal aid and are not remunerated equally’ and found both that women were more reliant on legal aid than men and that, even among those equally reliant on legal aid, women would earn a median 15.4% less than men.

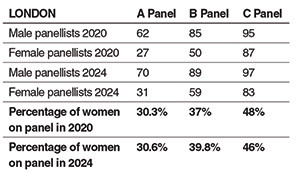

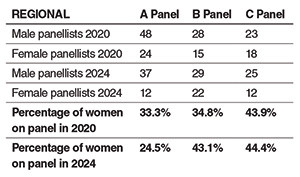

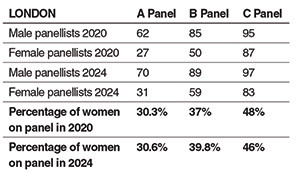

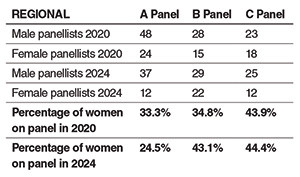

Returning to the data from the GLD, it seems that little has changed in the composition of the panels of junior barristers who may be instructed in government work. As of June 2024:

This significant gender disparity in instructing the available advocates is visible then across all panels and both in London and regionally. It is unexplained but may explain why men remain far more likely than women to move through the panels from C to A and then to the KC list.

The tables below show panel composition currently and in the last year pre-pandemic:

Therefore, from the limited data we have we can extrapolate the following key findings:

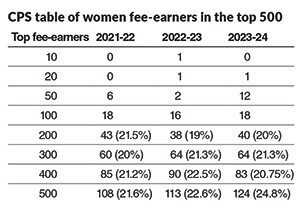

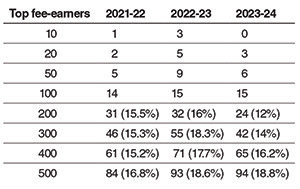

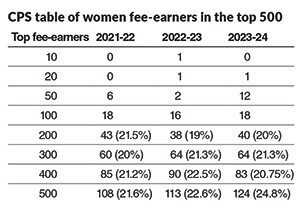

Turning to the criminal Bar, data collection and monitoring is much more robust and detailed. Therefore, we can ascertain with confidence and relative precision the gender split of income received both defending and prosecuting. As in previous years I have analysed the top 500 fee earners in each area, since beyond that criminal barristers are more likely to have mixed practices, making gender patterns difficult accurately to extrapolate.

Before examining the top 500 fee-earners under both the LAA and the CPS, it is worth noting the Bar Council’s analysis for year-end 2023. The methodology was slightly different, analysing the declared income of self-employed barristers deriving at least 80% of their income from criminal work generally. The Bar Council analysis indicates that women comprise 33% of this cohort but received 26% of the earnings that year. The largest differential was after 11 years’ call when women earned on average 22% less than men. Women silks earned on average 20% less than male silks.

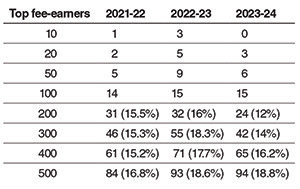

At the defence Bar, LAA data shows the number of women in brackets of top fee earners as follows:

Compared to 2019-20, the post-pandemic figures reveal no lessening of the inequity in the top 20 fee-earners, and a very slight percentage increase in the number of women in top 100-500, but the percentage never gets above 18.8% in any bracket.

There is, then, a clear and entrenched imbalance in criminal defence work allocation. Again, the Bar Council has called for better monitoring of work distribution by chambers: it says in its 2023 report: ‘The Bar Council has updated guidance for chambers on using earnings data to monitor work distribution and is working with chambers to improve monitoring and put in place interventions to address disparities. Detail is only available at a chambers level, and that is also where we will find most solutions.’

Mary Prior KC, Chair of the Criminal Bar Association, has been a longstanding, vocal and highly effective advocate for the criminal Bar generally and for equitable meritocracy specifically. She told me: ‘The disparity in earnings demonstrated in this excellent article between men and women who defend criminal cases remains steadfast. This must change for us to retain our women barristers and for us to recruit new talent. Transparency and data collection is essential.

‘Those solicitors who can demonstrate equality of earnings in their instructions to barristers should be applauded and recognised as pioneers within the profession. All firms should be obliged to collect data which can be checked by the Law Society to demonstrate that they are advancing equality and diversity. Chambers must do the same and should advertise the fact that there is equality of income in their set. Perhaps practitioners who are not in such a set would move to a set where they are properly valued.’

What about the other side of the criminal coin?

Compared to 2019-20 the CPS has done better beyond the top 100 fee-earners; the biggest percentage increase is in the top 200 where the proportion of women has increased from 14% to 20%. Women have broken the 20% barrier in the top 200, 300, 400 and 500 fee-earners for the first time, and consistently, over each of the last three years.

This glimmer of improvement in the CPS figures – particularly when compared to the lack of movement in equitable defence income – may reflect the considerable amount of work that the CPS has undertaken to record, analyse and address inequity in briefing patterns which I set out in my last report. Sharing the post-pandemic data, Michael Hoare, whose CPS HQ team oversees the Advocate Panel arrangements, told me: ‘The CPS Briefing Principles were published in June 2021, alongside a revised CPS Diversity and Inclusion Statement for the Bar. The Principles specifically reference equality of opportunity and support for development and progression as key factors when making decisions on the allocation of work. Meanwhile, the Diversity and Inclusion Statement places an expectation on CPS Advocate Panel members that they will self-declare their protected characteristics.

‘Although there is still work to do, as at January 2025 84% of the General Crime Panel – junior advocates prosecuting in the Crown Court – have made that declaration, meaning that we can test whether we are delivering against those principles. The figure is slightly lower in respect of non-Panel advocate declarations, which includes KCs, at 66% but we are working to increase it. We introduced the Treasury Counsel Pathway a couple of years ago to identify and support talented advocates from underrepresented groups who aspire to become the Treasury Counsel of the future. The 2024 recruitment round for Treasury Counsel monitorees was the first opportunity to test the success of that programme and I am pleased to say that three of the 11 monitoree appointments were pathway participants.’

Where there has been no movement, however, is in the top 20 fee-earners: consistently over the last seven years only one of the top 20 fee-earners has been female, save for 2020/21 where there were three women in the top 20, albeit this was the year in which courts were closed for months due to the pandemic. Why at the very top of the criminal prosecution tree is there such a scarcity of women? In the last two fiscal years, the CPS paid 321 KCs, of whom 73 were female, so 23% – which, if work were evenly distributed, should equate to at least four women in the top 20 for those two years. The Bar Council figures suggest that in May 2024, 89 of 396 self-employed silks practising at the criminal Bar were female – 22% – so the respective percentages imply that the CPS is instructing proportionately. Yet the dearth of women in the top 20 fee-earners suggest that the female silks are not being instructed as extensively or in as high value work as their male counterparts.

Michael Hoare told me: ‘We haven’t undertaken any recent analysis on the top 50, but I think geography is a relevant factor both in terms of the availability of female silks who prosecute and access to work. For example, there are some Circuits where there are very few female silks who prosecute, meaning that securing their services can be a challenge because they are in demand. Increasing numbers on some Circuits would have a significant impact. There are also several CPS regional areas located away from the main concentration of criminal sets in Birmingham, Leeds and London. This means that the choice and diversity of available advocates can be limited. More generally, we would acknowledge that, while we have taken a series of positive measures to address things, cultural change does take time and will require ongoing commitment and collaboration between the CPS, the Bar and the chambers we work with.’

The last round of Treasury Counsel recruitment was March 2024; currently three of the seven Senior Treasury Counsel are female (the same as previously) as are five of the 11 Junior Treasury Counsel (up from four). Further, six of the 11 barristers currently being monitored for Treasury Counsel are female (double the previous number), two of whom participated in the pathway. It is to be hoped that the better gender balance at Treasury Counsel level and the work that is being done surrounding KC instruction on Circuit will be reflected in the CPS earnings tables for future years.

Chair and founder of Women in Criminal Law, Katy Thorne KC said: ‘WICL applauds this study. It’s important to shine a light on gender inequality in fees. We were happy to work with the CPS on improving equality in briefing and applaud the progress they’ve made. We can all see there is work still to do in making sure women earn at the same levels as men. The challenge going forward is how to roll that progress over to the defence. There is an argument that the government, through the Legal Aid Agency contracting and auditing process, should insist that contracted solicitors firms undertake briefing policy monitoring.’

While still far from balanced, the CPS has shown that through comprehensive review and the consequent implementation of processes surrounding both data monitoring and work allocation, it is possible to address the continuing and significant gender pay gap at the Bar. Of the public bodies responsible for work allocation, the CPS has devised and implemented robust procedures to try to ensure that allocation is equitable and appropriately diverse. It is the only one that has been able to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement, notwithstanding the top 20 fee-earners remain stubbornly almost exclusively male. There was never going to be a quick or easy solution, but without robust systems to record, retain and analyse data relating to work allocation and remuneration there can be no solution. The CPS has worked hard to review, understand and address the imbalances in its briefing policies and practice; that work seems to be bearing fruit. The GLD acting on behalf of the Attorney General has undertaken to follow suit: Ms McGibbon said that it ‘has now established a targeted project to give an enhanced focus to this important agenda and drive forward progress’.

This will be my last report on this issue. However, I look forward to reading reports in future years showing that comprehensive and robust data monitoring and analysis is in place throughout all organisations that brief the Bar as well as in all barristers’ chambers, leading to a diminution of the current, longstanding significant imbalances in work allocation and income.

In this special International Women’s Day issue of Counsel it seems apt to give the last word to Barbara Mills KC, the first Black Chair of the Bar, and leader of its first all-female officer team. She told me: ‘It is incredibly useful to bring all this data together. It highlights the differences in earnings – and demonstrates that disparities and opportunities for work for women continue. What is clear is that more detailed and focused analysis on who gets the work leads to a closing of the gap between men and women. This has been shown by the CPS who have put significant time and effort into not just setting new principles but also putting in place systems which track work and highlight disparities as they occur. In our work with chambers and other parts of the Bar, we have also seen this approach to be effective and are convinced change is possible.

‘If there is a gap in data or information the Bar Council can work with all the government agencies to support better analysis. We worked with the CPS, and this led to an effective outcome. We would welcome the opportunity to work in a similar way with all parts of the government’s legal service.’

As Counsel was about to go to press, the Treasury Solicitor wrote to inform me of the significant increase to GLD counsel fees that she had secured – in part due to the diversity concerns raised in this and in my previous 2021 report.

Announcing a 25% increase in panel fees effective from 1 April, Susanna McGibbon told me: ‘Ensuring that government can access the highest quality of legal advice is essential to upholding good governance and decision-making within the rule of law. External legal counsel provide an essential part of this capability. As you know, the rates paid to counsel for undertaking work for government have not increased for around 20 years and there has long been concern in the legal sector as a result.’

Having considered an advance copy of this report, Ms McGibbon went on to say: ‘It is also clear that the current rates have had a negative impact on the diversity of counsel willing to do government work. As we have discussed previously, the GLD is committed to improving its instruction practice and ensuring that we instruct more diverse counsel – to be supported by better data. This is an issue that is of great personal importance to both myself and the Attorney General. To that end, my department has launched a Panel Counsel Diversity project to analyse this issue in more detail… We have also put in place a mechanism to ensure that fees are reviewed on a regular basis to ensure they continue to support access to diverse, high-quality counsel.’

For the past decade, chipping away at the glass ceiling with the meticulous stubbornness of a data-obsessed archaeologist – unearthing income and instruction statistics where they exist, and gently nudging public bodies to scribble some down where they don’t – has often felt less like progress and more like a self-inflicted concussion. But driving change – which seems to shuffle in like a tortoise on tranquillisers – requires unwavering patience and determination. I’ve seen firsthand such tirelessness in organisations like Women in the Law UK, WICL and Her Bar which have all been swinging sledgehammers. While that ceiling has yet to break, I’m pleased that my work – through polite, mutually respectful and evidence-based conversations with the Treasury Solicitor, the GLD, the CPS and the Bar Council – has at least caused a few cracks.

This is fifth and concluding part of HHJ Emma Nott’s ground-breaking earnings analysis. Read the whole series on the Counsel website:

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (1)’, Counsel, April 2018.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (2)’, Counsel, May 2018.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (3)’, Counsel, December 2019.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (4)’, Counsel, January 2021.

Gender Pay Gap Table, Bar Council, November 2020.

Income at the Bar - by Gender and Ethnicity, Research report, Bar Standards Board, November 2020.

Barrister earnings by sex and practice area 20 year trends report, Bar Council, September 2021.

Income at the Bar - by Gender and Ethnicity, Research report, Bar Standards Board, February 2022.

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar, Bar Council, November 2023.

Bar Council’s response to the Review of Civil Legal Aid - Call for Evidence, Bar Council, February 2024.

New practitioner earnings differentials at the self-employed Bar, Bar Council, April 2024.

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, February 2025.

CPS Briefing Principles, June 2021.

CPS Diversity and Inclusion Statement for the Bar, June 2021.

See the Bar Council Earnings Monitoring toolkit for chambers to calculate work distribution within sets and the

Bar Council Practice review guide for barristers and clerks which outlines review processes.

Cover image taken from HHJ Emma Nott’s presentation at the Czech Judicial Academy Seminar in Prague, 6 November 2024 on ‘Domestic and sexualised violence – victimological aspects: addressing risk and displacing stereotypes in the criminal justice system – the need for data and for expertise’.

.jpg?sfvrsn=1759a295_1)

Since 2018 I have analysed and reported on data showing the significant work and pay imbalance between the sexes at the self-employed publicly funded Bar, focusing first on the criminal Bar, and latterly including the Government Legal Department (GLD) which administers the panels on behalf of the Attorney General.

The figures I reported pre-pandemic were sufficiently stark to cause both the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the GLD to undertake their own internal reviews, which in turn led to the CPS implementing policies and procedures to record, retain and analyse their respective briefing patterns to avoid inequity, and the GLD stating that it would follow suit.

The Bar Council also transformed its own recording and reporting, and began publishing detailed reports on receipts by gender and ethnicity through analysing the practising certificate declarations that all self-employed barristers are required annually to submit to the Bar Mutual Indemnity Fund (BMIF). Its first such report, published in 2020, corresponded with my analyses of publicly funded work allocation, and further demonstrated a very significant gender income gap in every area of practice and at every level of call, starting in the first year of practice and continuing into silk. There were some limitations – in particular the data analysis was impaired by the fact that BMIF does not collect monitoring data on barristers and therefore sex had to be inferred from prefixes. Barristers who did not supply a prefix, or used a gender neutral prefix such as Dr, were therefore excluded from the data analysis.

The Bar Council further refined its approach in its next detailed report, Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar, in November 2023. It based its analysis on its own data received from each member of the Bar when they renew their practising certificate, and thus was able more comprehensively to analyse by reference to sex and to practice area. Little if anything has changed post-pandemic; of most concern is the Bar Council’s finding that the disparity starts from day one of a barrister’s career. The Bar Council examined post-qualification years 0-3 more closely in an April 2024 report, New practitioner earnings differentials at the self-employed Bar. It looked at the three practice years to March 2024 and concluded that a gap of between 9% and 13% exists at every post-qualification year from 0-3, exists across every area of practice, and exists both among barristers who have caring responsibilities and among those who do not. Further, of those for whom legal aid work comprises at least three quarters of their earnings, women at 0-3 years’ PQE earn on average 13% less than their male counterparts. The report also found that where chambers give barristers regular practice reviews and have policies to ensure the fair allocation of led work, then earnings gaps are reduced.

I was subsequently asked by several senior female members of the Bar (criminal and civil practitioners) to look again at work allocation and receipts at the publicly funded Bar to see if any of the measures put in place since I started reporting were working. Anecdotally, they each felt that despite the various promised measures and recommendations, little had changed on the ground. This unease has been reflected in discussions between the Treasury Solicitor with the Administrative Law Bar Association, with the Inns of Court Alliance for Women and with female GLD panel counsel members, who have made clear their perception that high quality work is not available for women as they rise through the government panels.

The Bar Council November 2023 report gives foundation to this perception. It concluded that while men’s and women’s gross earnings had both slightly increased in year ending April 2023 (the first full practice year following the pandemic) the difference in gross earnings between men and women at all call levels and in all areas of practice has not narrowed. Further, the Bar Council’s latest report, published on 4 February 2025, shows a worsening situation: not only does the income gap between the sexes persist at every call level and in every practice area, but it is increasing. In the calendar year 2023 junior women at the self-employed Bar earned on average 77% of the earnings of their male colleagues; in silk the women earned on average 67% of their male colleague’s median earnings.

What then, can we learn from the allocation of publicly funded instructions? I again approached the criminal department of the Legal Aid Agency (LAA), the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the Attorney General’s Office and the Treasury Solicitor. I am grateful to all for sharing their data.

Key findings in my 2021 report on GLD instruction:

The GLD recorded ‘instructions’ not as individual cases, but as cases invoiced per quarter: if a barrister invoiced a single case four times per quarter, that was recorded as one instruction; if she invoiced on that same case once per quarter over a year, that was recorded as four instructions. This made it very difficult properly to understand how equitable or otherwise allocation of work was. At the time, the Attorney General’s Office told me: ‘Successive Law Officers have been keen to advance equality of opportunity between men and women at the Bar and the panels have been seen as a way of achieving this.’ However, it conceded that it did not keep central records relating to who was instructed, in which type of court or at what level, and had no centralised policy governing instructions save that the allocating lawyer instructing silks had to have regard to ‘encouraging diversity’. I was told: ‘Efforts are made to encourage applications [to the panels] from as wide a pool as possible and approaches are made to diversity groups including the Association of Women Barristers. Selection boards are comprised of men and women in equal numbers.’ Four years on, what is the result of those efforts?

Assessing equity of instruction via the GLD is still considerably hampered by the continued lack of any proper data monitoring within the Department. ‘Instructions’ remain recorded in the same way as in 2021. This is something Susanna McGibbon, Treasury Solicitor since 2021, frankly accepted. She was clear that she did not want to use the pandemic as an excuse, but nonetheless accepted that the progress hoped for when I last reported has not been made. Ms McGibbon told me: ‘As Treasury Solicitor I am very proud to lead a diverse department where women lawyers are overrepresented at every grade, and in contrast to the private sector, particularly so at the highest grades where the majority of legal directors and my three deputies are female. I am absolutely focused on ensuring the same diverse approach to the counsel we instruct, not just in gender but in all aspects of diversity so that the counsel who represent the government are more representative of the population as a whole. I have regularly discussed the diversity of the Civil Panel with the former and current Attorneys General, both of whom share an absolute commitment to the visible improvement in diversity in the counsel on their panels.

‘But I will be candid that we have not made as much progress as I would have liked, and there is more to do. I am committed to improving our instruction practice and supporting that with better data.

‘Historically our case management system has not been configured to record diversity data, so monitoring and reporting on diversity requires manual interrogation of our systems and searches on BAILII. In addition, our finance systems record numbers of “instructions” per quarter rather than individual cases or invoices, which makes it difficult to make accurate comparisons on instruction rates. We are making improvements to our current case management system to record diversity data about the panels in one place as well as tracking which counsel our lawyers are instructing. For the longer term, we are developing a new legal practice management system, and the ability to record and report on diversity of counsel instructed has been included in our requirements for the new system.’

While the ability to report and analyse gender patterns in GLD instructions consequently remains hampered, the Department was able to give me some useful data – in part by trawling BAILII – and I am grateful to it for undertaking this exercise, even if it is no real substitute for proper recording.

Data relating to King’s Counsel instructions from the GLD came in two categories – the KC list and non-list KCs. Ms McGibbon explained that there is no application process for KCs acting for government and therefore the KC list is simply a record of those who have previously worked for government or who have expressed an interest in doing so. As of June 2024, there were 450 silks on the KC list (civil and EU): 98 women (21.8%) and 352 men.

However, there is no requirement to be on the list for a KC to be instructed. This is reflected in the table below which sets out how many times male and female KCs have been instructed in the last 24 months:

We do not know the fiscal value of those instructions since the number of hours spent and billed is not monitored. From the information that has been supplied, we can see that:

One of the Bar Council 2023 report’s key findings was that women silks earn on average 71% of their male colleagues’ median gross earnings, which has since dropped to 67% according to the report published in February 2025. According to the Treasury Solicitor, the average hourly rate of male KCs instructed by government is currently £194; the average hourly rate for the female panel KCs is £187. Because of the lack of data monitoring there is no clear reason for this discrepancy. Ms McGibbon said: ‘The rate of £180 was effectively set in 2010 and has been largely frozen since that time, although a small number of KCs have successfully argued for a higher rate based on specialisms, particular experience and private sector comparators.’

It was only by reviewing BAILII that the GLD was able to tell me that in 2023 (calendar year), there were 17 KC appearances in the Supreme Court on behalf of the GLD, two of which were by women (12%) and that of 43 KC appearances in the Court of Appeal, eight were women (18.5%). There is foundation then, for the perception that women are not receiving the high-quality work as they move up the ranks. The new legal practice management system will hopefully allow for more accurate and helpful analysis based on income rather than ‘instructions’.

Turning to the junior Bar, the November 2023, April 2024 and February 2025 Bar Council reports conclude that men’s median gross earnings are higher than women’s in every call band and every area of practice. As already described, this significant gender gap begins at 0-3 years’ call where experience has much less bearing. 51% of barristers at this level are women; they account for 45% of the gross earnings. Therefore, men are better enabled to build their experience and portfolios right from the beginning of their careers. This is reflected in the gap between men’s and women’s median gross earnings by 11-15 years’ call. By this career stage 44% of barristers are women, but they receive only 34% of the gross earnings and earn on average 30% less than their male counterparts. At 16-20 years’ call 44% of barristers are women and they account for 33% of the gross earnings, earning 28% less than their male colleagues. Looking specifically at civil work, the Bar Council analysed the income of self-employed barristers declaring at least 80% of their income in one of the following four practice areas: family, commercial, Chancery and personal injury. Men significantly outearn women at every call stage in every area and dominate the highest earning practice areas: 79% of commercial barristers and 80% of Chancery specialists are men, and 90% of silks in both practice areas are men – and they significantly outearn the few women at every level.

On publicly funded civil work specifically, as part of the Review of Civil Legal Aid in 2023/24, the Bar Council created a dataset of eight years of legal aid payments to civil and family legal aid practitioners. Family work accounts for the majority of civil legal aid payments, with 73% of barristers in receipt of civil legal aid payments receiving them wholly for family work. In its formal Response to the Review’s call for evidence dated February 2024, the Bar Council stated: ‘Groups of advocates have different levels of reliance on civil legal aid and are not remunerated equally’ and found both that women were more reliant on legal aid than men and that, even among those equally reliant on legal aid, women would earn a median 15.4% less than men.

Returning to the data from the GLD, it seems that little has changed in the composition of the panels of junior barristers who may be instructed in government work. As of June 2024:

This significant gender disparity in instructing the available advocates is visible then across all panels and both in London and regionally. It is unexplained but may explain why men remain far more likely than women to move through the panels from C to A and then to the KC list.

The tables below show panel composition currently and in the last year pre-pandemic:

Therefore, from the limited data we have we can extrapolate the following key findings:

Turning to the criminal Bar, data collection and monitoring is much more robust and detailed. Therefore, we can ascertain with confidence and relative precision the gender split of income received both defending and prosecuting. As in previous years I have analysed the top 500 fee earners in each area, since beyond that criminal barristers are more likely to have mixed practices, making gender patterns difficult accurately to extrapolate.

Before examining the top 500 fee-earners under both the LAA and the CPS, it is worth noting the Bar Council’s analysis for year-end 2023. The methodology was slightly different, analysing the declared income of self-employed barristers deriving at least 80% of their income from criminal work generally. The Bar Council analysis indicates that women comprise 33% of this cohort but received 26% of the earnings that year. The largest differential was after 11 years’ call when women earned on average 22% less than men. Women silks earned on average 20% less than male silks.

At the defence Bar, LAA data shows the number of women in brackets of top fee earners as follows:

Compared to 2019-20, the post-pandemic figures reveal no lessening of the inequity in the top 20 fee-earners, and a very slight percentage increase in the number of women in top 100-500, but the percentage never gets above 18.8% in any bracket.

There is, then, a clear and entrenched imbalance in criminal defence work allocation. Again, the Bar Council has called for better monitoring of work distribution by chambers: it says in its 2023 report: ‘The Bar Council has updated guidance for chambers on using earnings data to monitor work distribution and is working with chambers to improve monitoring and put in place interventions to address disparities. Detail is only available at a chambers level, and that is also where we will find most solutions.’

Mary Prior KC, Chair of the Criminal Bar Association, has been a longstanding, vocal and highly effective advocate for the criminal Bar generally and for equitable meritocracy specifically. She told me: ‘The disparity in earnings demonstrated in this excellent article between men and women who defend criminal cases remains steadfast. This must change for us to retain our women barristers and for us to recruit new talent. Transparency and data collection is essential.

‘Those solicitors who can demonstrate equality of earnings in their instructions to barristers should be applauded and recognised as pioneers within the profession. All firms should be obliged to collect data which can be checked by the Law Society to demonstrate that they are advancing equality and diversity. Chambers must do the same and should advertise the fact that there is equality of income in their set. Perhaps practitioners who are not in such a set would move to a set where they are properly valued.’

What about the other side of the criminal coin?

Compared to 2019-20 the CPS has done better beyond the top 100 fee-earners; the biggest percentage increase is in the top 200 where the proportion of women has increased from 14% to 20%. Women have broken the 20% barrier in the top 200, 300, 400 and 500 fee-earners for the first time, and consistently, over each of the last three years.

This glimmer of improvement in the CPS figures – particularly when compared to the lack of movement in equitable defence income – may reflect the considerable amount of work that the CPS has undertaken to record, analyse and address inequity in briefing patterns which I set out in my last report. Sharing the post-pandemic data, Michael Hoare, whose CPS HQ team oversees the Advocate Panel arrangements, told me: ‘The CPS Briefing Principles were published in June 2021, alongside a revised CPS Diversity and Inclusion Statement for the Bar. The Principles specifically reference equality of opportunity and support for development and progression as key factors when making decisions on the allocation of work. Meanwhile, the Diversity and Inclusion Statement places an expectation on CPS Advocate Panel members that they will self-declare their protected characteristics.

‘Although there is still work to do, as at January 2025 84% of the General Crime Panel – junior advocates prosecuting in the Crown Court – have made that declaration, meaning that we can test whether we are delivering against those principles. The figure is slightly lower in respect of non-Panel advocate declarations, which includes KCs, at 66% but we are working to increase it. We introduced the Treasury Counsel Pathway a couple of years ago to identify and support talented advocates from underrepresented groups who aspire to become the Treasury Counsel of the future. The 2024 recruitment round for Treasury Counsel monitorees was the first opportunity to test the success of that programme and I am pleased to say that three of the 11 monitoree appointments were pathway participants.’

Where there has been no movement, however, is in the top 20 fee-earners: consistently over the last seven years only one of the top 20 fee-earners has been female, save for 2020/21 where there were three women in the top 20, albeit this was the year in which courts were closed for months due to the pandemic. Why at the very top of the criminal prosecution tree is there such a scarcity of women? In the last two fiscal years, the CPS paid 321 KCs, of whom 73 were female, so 23% – which, if work were evenly distributed, should equate to at least four women in the top 20 for those two years. The Bar Council figures suggest that in May 2024, 89 of 396 self-employed silks practising at the criminal Bar were female – 22% – so the respective percentages imply that the CPS is instructing proportionately. Yet the dearth of women in the top 20 fee-earners suggest that the female silks are not being instructed as extensively or in as high value work as their male counterparts.

Michael Hoare told me: ‘We haven’t undertaken any recent analysis on the top 50, but I think geography is a relevant factor both in terms of the availability of female silks who prosecute and access to work. For example, there are some Circuits where there are very few female silks who prosecute, meaning that securing their services can be a challenge because they are in demand. Increasing numbers on some Circuits would have a significant impact. There are also several CPS regional areas located away from the main concentration of criminal sets in Birmingham, Leeds and London. This means that the choice and diversity of available advocates can be limited. More generally, we would acknowledge that, while we have taken a series of positive measures to address things, cultural change does take time and will require ongoing commitment and collaboration between the CPS, the Bar and the chambers we work with.’

The last round of Treasury Counsel recruitment was March 2024; currently three of the seven Senior Treasury Counsel are female (the same as previously) as are five of the 11 Junior Treasury Counsel (up from four). Further, six of the 11 barristers currently being monitored for Treasury Counsel are female (double the previous number), two of whom participated in the pathway. It is to be hoped that the better gender balance at Treasury Counsel level and the work that is being done surrounding KC instruction on Circuit will be reflected in the CPS earnings tables for future years.

Chair and founder of Women in Criminal Law, Katy Thorne KC said: ‘WICL applauds this study. It’s important to shine a light on gender inequality in fees. We were happy to work with the CPS on improving equality in briefing and applaud the progress they’ve made. We can all see there is work still to do in making sure women earn at the same levels as men. The challenge going forward is how to roll that progress over to the defence. There is an argument that the government, through the Legal Aid Agency contracting and auditing process, should insist that contracted solicitors firms undertake briefing policy monitoring.’

While still far from balanced, the CPS has shown that through comprehensive review and the consequent implementation of processes surrounding both data monitoring and work allocation, it is possible to address the continuing and significant gender pay gap at the Bar. Of the public bodies responsible for work allocation, the CPS has devised and implemented robust procedures to try to ensure that allocation is equitable and appropriately diverse. It is the only one that has been able to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement, notwithstanding the top 20 fee-earners remain stubbornly almost exclusively male. There was never going to be a quick or easy solution, but without robust systems to record, retain and analyse data relating to work allocation and remuneration there can be no solution. The CPS has worked hard to review, understand and address the imbalances in its briefing policies and practice; that work seems to be bearing fruit. The GLD acting on behalf of the Attorney General has undertaken to follow suit: Ms McGibbon said that it ‘has now established a targeted project to give an enhanced focus to this important agenda and drive forward progress’.

This will be my last report on this issue. However, I look forward to reading reports in future years showing that comprehensive and robust data monitoring and analysis is in place throughout all organisations that brief the Bar as well as in all barristers’ chambers, leading to a diminution of the current, longstanding significant imbalances in work allocation and income.

In this special International Women’s Day issue of Counsel it seems apt to give the last word to Barbara Mills KC, the first Black Chair of the Bar, and leader of its first all-female officer team. She told me: ‘It is incredibly useful to bring all this data together. It highlights the differences in earnings – and demonstrates that disparities and opportunities for work for women continue. What is clear is that more detailed and focused analysis on who gets the work leads to a closing of the gap between men and women. This has been shown by the CPS who have put significant time and effort into not just setting new principles but also putting in place systems which track work and highlight disparities as they occur. In our work with chambers and other parts of the Bar, we have also seen this approach to be effective and are convinced change is possible.

‘If there is a gap in data or information the Bar Council can work with all the government agencies to support better analysis. We worked with the CPS, and this led to an effective outcome. We would welcome the opportunity to work in a similar way with all parts of the government’s legal service.’

As Counsel was about to go to press, the Treasury Solicitor wrote to inform me of the significant increase to GLD counsel fees that she had secured – in part due to the diversity concerns raised in this and in my previous 2021 report.

Announcing a 25% increase in panel fees effective from 1 April, Susanna McGibbon told me: ‘Ensuring that government can access the highest quality of legal advice is essential to upholding good governance and decision-making within the rule of law. External legal counsel provide an essential part of this capability. As you know, the rates paid to counsel for undertaking work for government have not increased for around 20 years and there has long been concern in the legal sector as a result.’

Having considered an advance copy of this report, Ms McGibbon went on to say: ‘It is also clear that the current rates have had a negative impact on the diversity of counsel willing to do government work. As we have discussed previously, the GLD is committed to improving its instruction practice and ensuring that we instruct more diverse counsel – to be supported by better data. This is an issue that is of great personal importance to both myself and the Attorney General. To that end, my department has launched a Panel Counsel Diversity project to analyse this issue in more detail… We have also put in place a mechanism to ensure that fees are reviewed on a regular basis to ensure they continue to support access to diverse, high-quality counsel.’

For the past decade, chipping away at the glass ceiling with the meticulous stubbornness of a data-obsessed archaeologist – unearthing income and instruction statistics where they exist, and gently nudging public bodies to scribble some down where they don’t – has often felt less like progress and more like a self-inflicted concussion. But driving change – which seems to shuffle in like a tortoise on tranquillisers – requires unwavering patience and determination. I’ve seen firsthand such tirelessness in organisations like Women in the Law UK, WICL and Her Bar which have all been swinging sledgehammers. While that ceiling has yet to break, I’m pleased that my work – through polite, mutually respectful and evidence-based conversations with the Treasury Solicitor, the GLD, the CPS and the Bar Council – has at least caused a few cracks.

This is fifth and concluding part of HHJ Emma Nott’s ground-breaking earnings analysis. Read the whole series on the Counsel website:

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (1)’, Counsel, April 2018.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (2)’, Counsel, May 2018.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (3)’, Counsel, December 2019.

‘Gender at the Bar and fair access to work (4)’, Counsel, January 2021.

Gender Pay Gap Table, Bar Council, November 2020.

Income at the Bar - by Gender and Ethnicity, Research report, Bar Standards Board, November 2020.

Barrister earnings by sex and practice area 20 year trends report, Bar Council, September 2021.

Income at the Bar - by Gender and Ethnicity, Research report, Bar Standards Board, February 2022.

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar, Bar Council, November 2023.

Bar Council’s response to the Review of Civil Legal Aid - Call for Evidence, Bar Council, February 2024.

New practitioner earnings differentials at the self-employed Bar, Bar Council, April 2024.

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, February 2025.

CPS Briefing Principles, June 2021.

CPS Diversity and Inclusion Statement for the Bar, June 2021.

See the Bar Council Earnings Monitoring toolkit for chambers to calculate work distribution within sets and the

Bar Council Practice review guide for barristers and clerks which outlines review processes.

Cover image taken from HHJ Emma Nott’s presentation at the Czech Judicial Academy Seminar in Prague, 6 November 2024 on ‘Domestic and sexualised violence – victimological aspects: addressing risk and displacing stereotypes in the criminal justice system – the need for data and for expertise’.

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier