*/

Following details of his private life being splashed across the newspapers, Max Mosley brought a successful privacy action against News Group Newspapers Ltd in 2008.

He then complained to the European Court of Human Rights about the lack of any legal requirement in the UK for the press to notify an individual before publishing details about his or her private life. Here he explains why

The right to privacy is under scrutiny. The tabloid press would like to abolish it altogether. Politicians pretend to agree but have to think of the European Convention on Human Rights. Even from a victim’s perspective, however, current UK laws are unsatisfactory. But one simple reform would have a dramatic positive impact.

As I see it, UK privacy law has two fundamental problems. The first is cost: almost no one can afford a privacy trial. The second is futility: once revealed, private information can never again be private and a trial will only make things worse. As a result, if a newspaper illegally publishes intimate and very private details of a person’s life, he currently has no remedy.

Almost the first thing lawyers explain to a victim of invasion of privacy is that if he sues and loses, it will cost a fortune, but even if he wins, he will still be out of pocket. This is the so-called shortfall - the difference between the bill he gets from his solicitors and the total of costs and damages he recovers from the newspaper.

They will also tell him that the hearing will be in open court. The media, not just the newspaper he is suing, will publish the private and intimate details all over again. He will be warned they are likely to do this with embellishment under the protection of privilege.

Given this advice, no one in their right mind will sue once the story is out. The tabloid newspapers know this. That is why, when they intend to print something which they know is a clear and illegal invasion of privacy, they go to great lengths to stop the victim finding out before the newspaper is on the streets.

This happened to me. I had no inkling the story was coming. The newspaper was published before I found out. My lawyers explained the consequences of suing but, unlike other victims and perhaps foolishly, I went ahead. I felt outraged that the paper had quite deliberately flouted the law and made a mockery of my (human) rights.

The resulting figures are instructive. I was awarded £60,000 damages (a record for breach of privacy) and £420,000 costs. The bill from my lawyers was £510,000, leaving me £30,000 out of pocket. The newspaper’s contribution of over 80% towards my costs was unusually high. The shortfall would normally be greater.

So the result of my four days in the High Court was massive additional publicity about intimate and very personal matters that I wanted (and, as the court found, was entitled) to keep private, plus a bill for £30,000. I find it very difficult to imagine on what basis the Ministry of Justice think that was a remedy.

But even those who somehow think that was a remedy must see that litigation is beyond the reach of more than 95 per cent of the population. Even if someone were able to spend the £30,000, they would also have to consider the risks. No litigation is certain. Losing a privacy trial would cost in the order of £1 million. So even if the courts could provide a remedy after publication, few could sue without putting their entire way of life at risk.

You would think the solution is clear. Given that there is demonstrably no post-publication remedy - indeed the injury can only be made worse by litigation - the victim should be forewarned. Then, provided his private life is not a matter of legitimate public interest, he can attempt to safeguard his privacy by taking steps before the newspaper is published.

If the victim knows the story is coming and cannot reason with the newspaper, he has two possibilities. He can go to a judge and ask for an injunction to prevent publication. Not easy, but he will probably get one if he can show he is likely to win at trial. And the costs will be a small fraction of the costs of a full trial.

Or he can go to the Press Complaints Commission. Although pointless after publication (the PCC has no power to sanction and, at best, issues a mild rebuke and secures a small statement somewhere in the paper), the PCC can sometimes prevent illegal publication. And the PCC is free. But, as with injunctions, this remedy is only available if the victim is alerted and can go to the PCC before the newspaper is on the streets.

This means it is absolutely essential that a person is warned if a newspaper intends to publish intimate details of his private life. Then, but only then, will he have a remedy - provided, of course, that it is not successfully argued that there is a public interest in the details being revealed.

There is a massive media lobby in the UK against prior notification. Primarily the tabloids, but even serious newspapers join in. Yet, according to Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre (in evidence to a Parliamentary Select Committee) “in 99 cases out of a hundred” the subject is anyway contacted beforehand.

The truth is that full-on media ambushes, where the victim is kept in the dark until after publication, always involve sex. Ambushes are confined to extreme cases where the newspaper knows perfectly well that the information is very private and there is no public interest in its exposure. Newspapers go to great lengths to keep their intentions secret when they know a court or the PCC would intervene if given the opportunity to do so. In my own case, there was a dummy first edition, which was available in London on a Saturday evening but was destined for the furthest corners of the United Kingdom; the second and subsequent editions carried the story and were published in the areas with the largest circulation.It is extraordinary, then, you might think, that the government does not simply bring in the necessary legislation and insist that details of a person’s sex life can only be published if that person has been forewarned. The gap in the law would then be closed.

The problem is our politicians will not do this. They know that any restrictions on the ability of the tabloids to peddle details of people’s sex lives would affect profits. Rupert Murdoch and the other tabloid proprietors are too powerful to annoy, so the government does nothing.

So, where does that leave us? Let’s take an extreme case. Suppose a tabloid conceals a camera in the hotel room of a well-known couple and films them making love. This is kept secret and the first the pair know is when they see the pictures in the newspaper and the film on the internet.

Outraged, they go to their lawyers. They get the standard post-publication advice - there’s nothing to be done: legal action will merely make matters worse and will cost a lot of money. The paper is on the streets and the film is on the internet. If they go to a judge he will say: sorry, it’s already all over the world, I don’t want to be King Canute.

Perhaps you think that could not happen and that no newspaper would film people making love in private and publish the pictures? Well, like me, you probably didn’t think the UK’s biggest newspaper, the News of the World, would turn to crime to boost its sales. And like everyone else, you probably believed Murdoch’s people when, for four years, they told the world it was just one rogue employee and they had “zero tolerance” of wrongdoing. It was quite a surprise when they were finally forced to admit to institutionalised criminality.

Without prior notification, we have to trust the editors. But we now know what we are dealing with. A News of the World editor re-hired the paper’s private detective, Jonathan Rees, when he came out of prison in 2005 after serving seven years for planting cocaine in the car of a divorced woman to help her former husband gain custody of their children. Asking a tabloid editor to respect privacy is like putting the mafia in charge of your bank account. Time and again, the tabloids have shown contempt for the law. If they can get away with it, they will.

It’s time for effective measures. This can only mean prior notification. Many countries would simply shut down newspapers which continually flout the law. That would not be the right thing to do in the UK. But the citizen should not be left defenceless when a tabloid decides to publish intimate details of his sex life in defiance of the European Convention.

A person’s privacy is one of his most precious and vulnerable possessions. The law should not allow it to be stolen by criminals and sold for profit on the streets.

Max Mosley

David Sherborne, 5 Raymond Buildings

David Sherborne, a member of the legal team which represented Max Mosley at the European Court of Human Rights, sets out the legal basis of the claim:

Following his successful privacy action against News Group Newspapers Limited in 2008, Max Mosley complained to the European Court of Human Rights about the lack of any legal requirement in the UK for the press to notify an individual in advance of an intention to publish a story about his or her private life. In his action against the News of the World, the newspaper had admitted deliberately concealing its intention to publish a story about his sex life because of the fear that he would be able to prevent this by way of an injunction.

Mr Mosley argued that this constituted an infringement of his Article 8 right to respect for his privacy, since the only effective or practical means to protect this right was the ability to prevent private or confidential information being published in the first place, as opposed to any afterwards by which time the damage had effectively been done.

After an oral hearing in Strasbourg in January of this year, the Court declared his complaint admissible but held that there had been no violation of Article 8 of the Convention. In its judgment of 10 May 2011, the Fourth Section of the European Court found that the News of the World had been responsible for “a flagrant and unjustified invasion” of Mr Mosley’s private life, through conduct which was “open to severe criticism”. It also held that the private lives of people in the public eye had been turned into a “highly lucrative commodity for certain sections of the media”, which type of reporting, in contrast to the proper role of the press as a public watchdog, should “not attract the robust protection of Article 10”.

However, the Court believed that such a prior notification requirement (which did not exist in any other contracting state) would be difficult to work in practice and might cause a chilling effect on Article 10, and in particular serious journalism, given the need for a public interest exception. In light of the wide margin of appreciation afforded to Member States in balancing the requirements of private life and freedom of expression, the Court therefore found no violation of Article 8. Mr Mosley has now appealed to the Grand Chamber under Article 43 of the Convention since the complaint raises a serious issue of general importance.

The right to privacy is under scrutiny. The tabloid press would like to abolish it altogether. Politicians pretend to agree but have to think of the European Convention on Human Rights. Even from a victim’s perspective, however, current UK laws are unsatisfactory. But one simple reform would have a dramatic positive impact.

As I see it, UK privacy law has two fundamental problems. The first is cost: almost no one can afford a privacy trial. The second is futility: once revealed, private information can never again be private and a trial will only make things worse. As a result, if a newspaper illegally publishes intimate and very private details of a person’s life, he currently has no remedy.

Almost the first thing lawyers explain to a victim of invasion of privacy is that if he sues and loses, it will cost a fortune, but even if he wins, he will still be out of pocket. This is the so-called shortfall - the difference between the bill he gets from his solicitors and the total of costs and damages he recovers from the newspaper.

They will also tell him that the hearing will be in open court. The media, not just the newspaper he is suing, will publish the private and intimate details all over again. He will be warned they are likely to do this with embellishment under the protection of privilege.

Given this advice, no one in their right mind will sue once the story is out. The tabloid newspapers know this. That is why, when they intend to print something which they know is a clear and illegal invasion of privacy, they go to great lengths to stop the victim finding out before the newspaper is on the streets.

This happened to me. I had no inkling the story was coming. The newspaper was published before I found out. My lawyers explained the consequences of suing but, unlike other victims and perhaps foolishly, I went ahead. I felt outraged that the paper had quite deliberately flouted the law and made a mockery of my (human) rights.

The resulting figures are instructive. I was awarded £60,000 damages (a record for breach of privacy) and £420,000 costs. The bill from my lawyers was £510,000, leaving me £30,000 out of pocket. The newspaper’s contribution of over 80% towards my costs was unusually high. The shortfall would normally be greater.

So the result of my four days in the High Court was massive additional publicity about intimate and very personal matters that I wanted (and, as the court found, was entitled) to keep private, plus a bill for £30,000. I find it very difficult to imagine on what basis the Ministry of Justice think that was a remedy.

But even those who somehow think that was a remedy must see that litigation is beyond the reach of more than 95 per cent of the population. Even if someone were able to spend the £30,000, they would also have to consider the risks. No litigation is certain. Losing a privacy trial would cost in the order of £1 million. So even if the courts could provide a remedy after publication, few could sue without putting their entire way of life at risk.

You would think the solution is clear. Given that there is demonstrably no post-publication remedy - indeed the injury can only be made worse by litigation - the victim should be forewarned. Then, provided his private life is not a matter of legitimate public interest, he can attempt to safeguard his privacy by taking steps before the newspaper is published.

If the victim knows the story is coming and cannot reason with the newspaper, he has two possibilities. He can go to a judge and ask for an injunction to prevent publication. Not easy, but he will probably get one if he can show he is likely to win at trial. And the costs will be a small fraction of the costs of a full trial.

Or he can go to the Press Complaints Commission. Although pointless after publication (the PCC has no power to sanction and, at best, issues a mild rebuke and secures a small statement somewhere in the paper), the PCC can sometimes prevent illegal publication. And the PCC is free. But, as with injunctions, this remedy is only available if the victim is alerted and can go to the PCC before the newspaper is on the streets.

This means it is absolutely essential that a person is warned if a newspaper intends to publish intimate details of his private life. Then, but only then, will he have a remedy - provided, of course, that it is not successfully argued that there is a public interest in the details being revealed.

There is a massive media lobby in the UK against prior notification. Primarily the tabloids, but even serious newspapers join in. Yet, according to Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre (in evidence to a Parliamentary Select Committee) “in 99 cases out of a hundred” the subject is anyway contacted beforehand.

The truth is that full-on media ambushes, where the victim is kept in the dark until after publication, always involve sex. Ambushes are confined to extreme cases where the newspaper knows perfectly well that the information is very private and there is no public interest in its exposure. Newspapers go to great lengths to keep their intentions secret when they know a court or the PCC would intervene if given the opportunity to do so. In my own case, there was a dummy first edition, which was available in London on a Saturday evening but was destined for the furthest corners of the United Kingdom; the second and subsequent editions carried the story and were published in the areas with the largest circulation.It is extraordinary, then, you might think, that the government does not simply bring in the necessary legislation and insist that details of a person’s sex life can only be published if that person has been forewarned. The gap in the law would then be closed.

The problem is our politicians will not do this. They know that any restrictions on the ability of the tabloids to peddle details of people’s sex lives would affect profits. Rupert Murdoch and the other tabloid proprietors are too powerful to annoy, so the government does nothing.

So, where does that leave us? Let’s take an extreme case. Suppose a tabloid conceals a camera in the hotel room of a well-known couple and films them making love. This is kept secret and the first the pair know is when they see the pictures in the newspaper and the film on the internet.

Outraged, they go to their lawyers. They get the standard post-publication advice - there’s nothing to be done: legal action will merely make matters worse and will cost a lot of money. The paper is on the streets and the film is on the internet. If they go to a judge he will say: sorry, it’s already all over the world, I don’t want to be King Canute.

Perhaps you think that could not happen and that no newspaper would film people making love in private and publish the pictures? Well, like me, you probably didn’t think the UK’s biggest newspaper, the News of the World, would turn to crime to boost its sales. And like everyone else, you probably believed Murdoch’s people when, for four years, they told the world it was just one rogue employee and they had “zero tolerance” of wrongdoing. It was quite a surprise when they were finally forced to admit to institutionalised criminality.

Without prior notification, we have to trust the editors. But we now know what we are dealing with. A News of the World editor re-hired the paper’s private detective, Jonathan Rees, when he came out of prison in 2005 after serving seven years for planting cocaine in the car of a divorced woman to help her former husband gain custody of their children. Asking a tabloid editor to respect privacy is like putting the mafia in charge of your bank account. Time and again, the tabloids have shown contempt for the law. If they can get away with it, they will.

It’s time for effective measures. This can only mean prior notification. Many countries would simply shut down newspapers which continually flout the law. That would not be the right thing to do in the UK. But the citizen should not be left defenceless when a tabloid decides to publish intimate details of his sex life in defiance of the European Convention.

A person’s privacy is one of his most precious and vulnerable possessions. The law should not allow it to be stolen by criminals and sold for profit on the streets.

Max Mosley

David Sherborne, 5 Raymond Buildings

David Sherborne, a member of the legal team which represented Max Mosley at the European Court of Human Rights, sets out the legal basis of the claim:

Following his successful privacy action against News Group Newspapers Limited in 2008, Max Mosley complained to the European Court of Human Rights about the lack of any legal requirement in the UK for the press to notify an individual in advance of an intention to publish a story about his or her private life. In his action against the News of the World, the newspaper had admitted deliberately concealing its intention to publish a story about his sex life because of the fear that he would be able to prevent this by way of an injunction.

Mr Mosley argued that this constituted an infringement of his Article 8 right to respect for his privacy, since the only effective or practical means to protect this right was the ability to prevent private or confidential information being published in the first place, as opposed to any afterwards by which time the damage had effectively been done.

After an oral hearing in Strasbourg in January of this year, the Court declared his complaint admissible but held that there had been no violation of Article 8 of the Convention. In its judgment of 10 May 2011, the Fourth Section of the European Court found that the News of the World had been responsible for “a flagrant and unjustified invasion” of Mr Mosley’s private life, through conduct which was “open to severe criticism”. It also held that the private lives of people in the public eye had been turned into a “highly lucrative commodity for certain sections of the media”, which type of reporting, in contrast to the proper role of the press as a public watchdog, should “not attract the robust protection of Article 10”.

However, the Court believed that such a prior notification requirement (which did not exist in any other contracting state) would be difficult to work in practice and might cause a chilling effect on Article 10, and in particular serious journalism, given the need for a public interest exception. In light of the wide margin of appreciation afforded to Member States in balancing the requirements of private life and freedom of expression, the Court therefore found no violation of Article 8. Mr Mosley has now appealed to the Grand Chamber under Article 43 of the Convention since the complaint raises a serious issue of general importance.

Following details of his private life being splashed across the newspapers, Max Mosley brought a successful privacy action against News Group Newspapers Ltd in 2008.

He then complained to the European Court of Human Rights about the lack of any legal requirement in the UK for the press to notify an individual before publishing details about his or her private life. Here he explains why

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

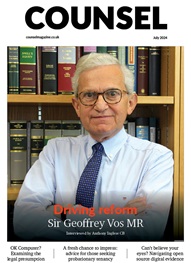

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts