*/

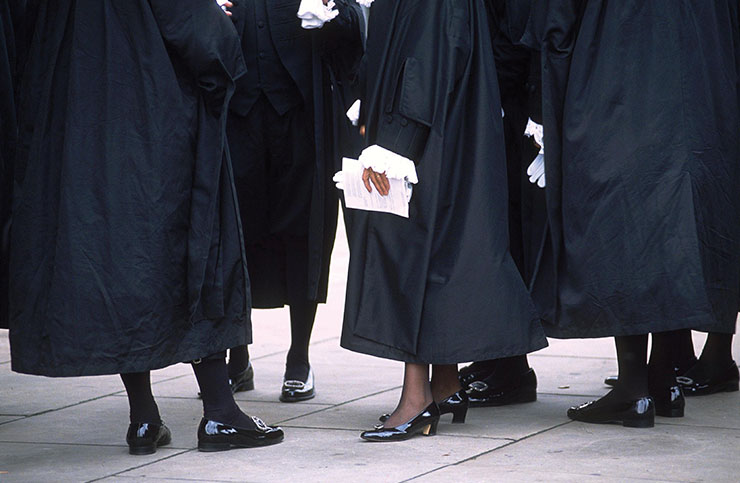

Celebrating the 114 new silks – plus forensic analysis of the 2019 cohort and what it says about equality of opportunity in the profession and health of the Bar –by David Wurtzel

The names of the 114 successful candidates for silk were announced on 16 January 2019. As part of its duties, the QC Appointments (QCA) Panel published a full report, analysing the cohort and explaining exactly how it went about the task. Looking through the online chambers profile of each successful candidate reveals even more about who got silk.

The number of applicants was 258. Last year it was 240, which is the average over the previous 11 years. Of the 258, 240 were self-employed barristers, or 1.5% of the junior Bar. Achieving a result that makes this tiny self-selected cohort representative of the Bar as a whole is a challenge. This is underlined by the fact that 24% of silks in 2019 came from a total of seven, London-based chambers. A further 11 sets (including two out of London) provided a further 22 new QCs, altogether making up 40% of the total of self-employed practitioners. Only six out of the 71 new civil QCs practise out of London, two out of the 11 new family silks, and nine out of the 26 new criminal silks.

One could conclude that the process is thus only relevant to a small part of the Bar, practising in chambers already rich in QCs. On average, each of the successful applicants in civil work is in chambers which already has 22 QCs. For those doing criminal work, the average is nine QCs in chambers and for those in family work, ten. There is only one new QC who will be the first QC in his chambers.

While QCA welcomes applications from all suitably qualified advocates, ‘applications are also particularly welcomed from women, members of ethnic minorities, people with disabilities and other groups that are currently under-represented’. At present, 17% of QCs are women and 8% are BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic), which is roughly half of their representation in the Bar at large.

The number of women and BAME applicants can obviously overlap. In 2019 there were 42 applications from BAME candidates, up from 30 the previous year. The number of women dipped slightly from 55 (50 the year before that) to 52. In both years, 30 women were successful. The dramatic change was in the success of BAME applicants: 22 were selected. It had never been more than 18 and that was in 2017. Also encouraging was the fact that the percentage of successful BAME applicants was roughly the same in each area of specialism, ie about 20%.

The question of encouraging more women applicants has concerned QCA since it was set up. Proportionately, women have always had a greater success rate than men in applying. Between 1995 and 2003, when the process was still run by the Lord Chancellor’s Department and the number of male applicants hovered around the 500 mark, the average number of women applicants was 45. QCA began selecting in 2006. From then to 2016, however, the average number of women applicants dipped to 43.4 – even though the number of women barristers was going up. The last three years have seen the raw numbers of applicants up to the 50s but the number of appointments are the same (31, 30, 30). Women, however, are still proportionately much more likely to be successful than men when applying – this year it was 58% as against 41% of the men.

The percentage of new women criminal silks is 31% (eight out of 26); of new family silks 45% (five out of 11), and of new civil silks, 21% (15 out of 71). Two out of six new QCs who practise in more than one area are women. This is all below their representation in the Bar.

What can be done? Obviously QCA is in no position to alter the culture of the Bar in terms of working practices, allocation of work or to add to existing mentoring schemes. All it can do is to accommodate applicants so that the process is not confined to those who have spent their entire professional career as advocates doing a succession of increasingly sophisticated cases in court. In 2017 QCA commissioned Balancing the Scales, a report from The Work Foundation and then consulted the professional bodies on its recommendations. QCA then undertook to change the application process in 2019.

Until then, applicants were expected to list eight judges, six fellow advocates and four clients as prospective assessors. This was held to be unfair. It had become commonplace for applicants to ask their assessors in advance if they were willing to provide an assessment. This was aimed at identifying those who were keen and willing and weeding out the merely lukewarm. But apparently only men did this; independent research showed that women were more reluctant to do so.

This time the applicants were asked to list 12 cases of substance, complexity etc and for each one to list a judicial and practitioner assessor and up to six client assessors. So now there could be up to 30 assessors, and 33% of applicants managed to achieve this. On the other hand, 22 applicants named fewer than eight different judicial assessors and ten named fewer than six although they provided a satisfactory explanation for that. The report does not say who they were in terms of gender or the correlation between numbers of assessors and who was asked to interview and then recommended for appointment.

One needs to know if women applicants did find the new system (there were other changes as well) more suitable to their practices. We already know that at least in this year it did not lead to an increase in women applicants. All assessors were asked to rate the applicant in respect of each of the required competencies. 97% of clients rated the candidate very good or excellent but only 82% of judges did so and 84% of fellow practitioners.

After the papers sift, 181 applicants or 70% (but 81% of the women applicants) were invited to interview. Of those 63% were selected. As in the past, the more successful were the first-timers: 50% versus 35% of those who had applied in at least one of the last three competitions. 31% of returnees were not invited for interview regardless of whether they had been in the past.

QCA maintains diversity statistics, in addition to those relating to gender and ethnicity cited above. Eight applicants identified themselves as gay; six were recommended for appointment. Ten declared a disability; three were appointed. Youth prevailed: 57% of the 21 applicants under the age of 40 who applied were recommended but only 29% of the 89 aged 51 and over.

There is no attempt to obtain information regarding applicants’ education or their socio-economic background despite QCA’s traditional assurance that the rank of QC is not confined to those who attended Oxford or Cambridge let alone a fee-paying school. Barristers in civil chambers are more forthcoming about their education as part of their profile on the chambers website than those doing publicly funded work. Of the 71 civil QCs, 51 give their universities. Of these 31 are Oxford or Cambridge and 18 are other Russell Group universities. Of the 11 family QCs, five give their universities – two Oxbridge, three other Russell Group. Of the 25 criminal QCs, ten give their universities – three Oxford, and seven other Russell Group universities.

The QCA report concludes: ‘The agreed process was designed to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointment with the assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants. We remain concerned that the level of applications from solicitor advocates remains comparatively low.’ Once again, QCA undertakes to liaise with the Solicitors’ Association of Higher Courts Advocates and the Law Society to explore what can be done ‘to overcome this problem’. Nine solicitors applied this year, seven were interviewed and four were recommended for appointment. They, like one of the two employed barristers (the other is a woman and a CPS Crown Advocate), are partners in ‘magic circle’ solicitors’ firms operating out of Paris or Hong Kong, and engaged in international arbitration, which at the Bar would be labelled ‘niche’.

Does the list say anything about the health of the Bar? Is the number of cases requiring a QC and/or more than one counsel increasing or shrinking? Overall, the numbers of new QCs is buoyant and much higher than it was until a few years ago. The criminal Bar’s new QC numbers dipped to 17 in 2015-16 but then rose to 38, 40 and 39 in the next three competitions. This time it was down to 26. The number of family silks, which had averaged 7.5, atrophied to six and then four last year but this time was up to 11 (plus two with combined practices). The majority of these specialised in children matters. The civil Bar – which includes a very wide range of work – resumed its dominant position, with 71 or 62% of the total.

The Panel sees no diminution in quality. Whoever the non-applicants are, amongst those who do apply, QCA is spoiled for choice.

The statistics in this article were updated on 7 February 2020.

Elizabeth Gardiner CB; Lynda Gibbs; Millicent Grant; Professor Eva Lomnicka; Glyn Maddocks; Professor Judith Masson; Professor Clare McGlynn; Rodger Pannone; Professor Jane Stapleton; Daniel Winterfeldt

Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Barnard | Jonathan James |

| Mr | Brady | Michael Antony |

| Ms | Brown | Cameron Kennedy Duncan |

| Mr | Clare | Allison Jean |

| Mr | Cooper | Ben Lion |

| Mr | de la Poer | Nicholas John |

| Mr | Ford | Mark Steven |

| Mr | Garcha | Gurdeep Singh |

| Mr | Graffius | Mark Narayan |

| Mr | Hipkin | John Leslie |

| Mr | Hossain | Syed Ahmed Izharul |

| Miss | Hussain | Frida |

| Mr | Kazakos | Leon Samuel |

| Miss | Knight | Jennifer Claudia |

| Mr | Langdale | Adrian Mark |

| Mr | Mohindru | Anurag |

| Miss | Newell | Charlotte Anne |

| Miss | Osborne | Jane Elizabeth |

| Mr | Raudnitz | Paul Nikolai |

| Mr | Reiz | Stanley |

| Mr | Sandiford | Jonathan |

| Ms | Simpson | Melanie Denise |

| Miss | Stonecliffe | Heidi Lorraine |

| Mr | Storrie | Timothy James |

| Ms | Summers | Allison |

| Mr | Wood | Stephen |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Miss | Bowcock | Samantha Jane |

| Mrs | Carew Pole | Rebecca Jane |

| Miss | Hillas | Samantha |

| Mr | Kingerley | Martin Goddard |

| Ms | Mills | Barbara |

| Mr | Mitchell | Peter |

| Mr | Oliver | Harry John William |

| Ms | Perry | Cleo |

| Mr | Roche | Brendan |

| Mr | Sampson | Jonathan Robert |

| Mr | Webster | Simon Mark |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Adamson | Dominic James |

| Mr | Barclay | Robin Nicholas John |

| Mr | Butt | Matthew Paul |

| Mr | Hodivala | Jamas Rusi |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Allen | William Andrew |

| Mr | Atkins | Siward |

| Ms | Barton | Zoë Maria Marsden |

| Mr | Blackaby | Nigel Alexander |

| Mr | Blundell | David Anthony |

| Mr | Boardman | Christopher Leigh Wilson |

| Mr | Buckingham | Stewart John |

| Mr | Byam-Cook | Henry James |

| Miss | Carpenter | Chloe |

| Mr | Carpenter | James Frederick Horatio |

| Mr | Chapman | Simon James |

| Mr | Collingwood | Timothy Donald |

| Mr | Cowen | Gary Adam |

| Mr | Dignum | Marcus Benedict |

| Mr | Doyle | Louis George |

| Mr | Duncan | Delroy Benell |

| Mr | Fisher | Richard Mark |

| Mr | Fry | Jason Alva |

| Mr | Goatley | Peter Seamus Patrick |

| Mr | Goldsmith | James Daniel |

| Mr | Grantham | Andrew Timothy |

| Mr | Hall Taylor | Alexander Edward |

| Mr | Higgo | Justin Beresford |

| Ms | Jhangiani | Sapna |

| Ms | Leahy | Blair Patricia |

| Miss | Lee | Krista |

| Mr | Levey | Edward Michael |

| Mr | Liddell | Richard Ian |

| Mr | Lynch | Benjamin John Patrick |

| Mr | Lyness | Scott Edward |

| Mr | Majumdar | Shantanu Joseph |

| Mr | Mallalieu | Roger |

| Ms | McColgan | Aileen |

| Mr | McDougall | Andrew de Lotbinière |

| Professor | McMeel | Gerard Patrick |

| Mr | Mehrzad | John |

| Mr | Milford | Julian Robert |

| Ms | Mitrophanous | Eleni |

| Mr | Mold | Andrew Matthew Stephen |

| Ms | Newton | Katharine Julia |

| Mr | Norris | Andrew James Steedsman |

| Ms | Omambala | Ijeoma Chinyelu |

| Ms | Oppenheimer | Tamara Helen Pasternak |

| Mr | Panesar | Deshpal |

| Mr | Patton | Conall |

| Mr | Pickering | James Patrick |

| Mr | Pievsky | David Richard |

| Mr | Pilgerstorfer | Marcus James |

| Mr | Pillai | Rajesh |

| Mr | Pitchers | Henry William Stodart |

| Ms | Plowden | Sarah Selena Rixar |

| Mr | Riches | Philip Geoffrey Hurry |

| Mr | Richmond | Jeremy John |

| Mr | Rosenthal | Adam Julius |

| Mr | Rubins | Noah Daniel |

| Mr | Salve | Harish |

| Ms | Savage | Amanda Claire |

| Dr | Scannell | David Luke |

| Mr | Segan | James Jeffrey |

| Miss | Selway | Katherine Emma |

| Mr | Shivji | Sharif Asim |

| Mr | Simblet | Stephen John |

| Mr | Speker | Adam |

| Miss | Thomas | Jacqueline Louise |

| Mr | Thornton | Andrew James |

| Ms | Tuck | Rebecca Louise |

| Mr | Wald | Richard Daniel |

| Mr | Warwick | Henry |

| Mr | West | Colin |

| Mr | Wheeler | Giles Neil Laurence |

| Mr | Williams | Robert Brychan James |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Ms | Carter-Manning | Jennifer Anne |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Miss | Munroe | Veronica Allison |

The names of the 114 successful candidates for silk were announced on 16 January 2019. As part of its duties, the QC Appointments (QCA) Panel published a full report, analysing the cohort and explaining exactly how it went about the task. Looking through the online chambers profile of each successful candidate reveals even more about who got silk.

The number of applicants was 258. Last year it was 240, which is the average over the previous 11 years. Of the 258, 240 were self-employed barristers, or 1.5% of the junior Bar. Achieving a result that makes this tiny self-selected cohort representative of the Bar as a whole is a challenge. This is underlined by the fact that 24% of silks in 2019 came from a total of seven, London-based chambers. A further 11 sets (including two out of London) provided a further 22 new QCs, altogether making up 40% of the total of self-employed practitioners. Only six out of the 71 new civil QCs practise out of London, two out of the 11 new family silks, and nine out of the 26 new criminal silks.

One could conclude that the process is thus only relevant to a small part of the Bar, practising in chambers already rich in QCs. On average, each of the successful applicants in civil work is in chambers which already has 22 QCs. For those doing criminal work, the average is nine QCs in chambers and for those in family work, ten. There is only one new QC who will be the first QC in his chambers.

While QCA welcomes applications from all suitably qualified advocates, ‘applications are also particularly welcomed from women, members of ethnic minorities, people with disabilities and other groups that are currently under-represented’. At present, 17% of QCs are women and 8% are BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic), which is roughly half of their representation in the Bar at large.

The number of women and BAME applicants can obviously overlap. In 2019 there were 42 applications from BAME candidates, up from 30 the previous year. The number of women dipped slightly from 55 (50 the year before that) to 52. In both years, 30 women were successful. The dramatic change was in the success of BAME applicants: 22 were selected. It had never been more than 18 and that was in 2017. Also encouraging was the fact that the percentage of successful BAME applicants was roughly the same in each area of specialism, ie about 20%.

The question of encouraging more women applicants has concerned QCA since it was set up. Proportionately, women have always had a greater success rate than men in applying. Between 1995 and 2003, when the process was still run by the Lord Chancellor’s Department and the number of male applicants hovered around the 500 mark, the average number of women applicants was 45. QCA began selecting in 2006. From then to 2016, however, the average number of women applicants dipped to 43.4 – even though the number of women barristers was going up. The last three years have seen the raw numbers of applicants up to the 50s but the number of appointments are the same (31, 30, 30). Women, however, are still proportionately much more likely to be successful than men when applying – this year it was 58% as against 41% of the men.

The percentage of new women criminal silks is 31% (eight out of 26); of new family silks 45% (five out of 11), and of new civil silks, 21% (15 out of 71). Two out of six new QCs who practise in more than one area are women. This is all below their representation in the Bar.

What can be done? Obviously QCA is in no position to alter the culture of the Bar in terms of working practices, allocation of work or to add to existing mentoring schemes. All it can do is to accommodate applicants so that the process is not confined to those who have spent their entire professional career as advocates doing a succession of increasingly sophisticated cases in court. In 2017 QCA commissioned Balancing the Scales, a report from The Work Foundation and then consulted the professional bodies on its recommendations. QCA then undertook to change the application process in 2019.

Until then, applicants were expected to list eight judges, six fellow advocates and four clients as prospective assessors. This was held to be unfair. It had become commonplace for applicants to ask their assessors in advance if they were willing to provide an assessment. This was aimed at identifying those who were keen and willing and weeding out the merely lukewarm. But apparently only men did this; independent research showed that women were more reluctant to do so.

This time the applicants were asked to list 12 cases of substance, complexity etc and for each one to list a judicial and practitioner assessor and up to six client assessors. So now there could be up to 30 assessors, and 33% of applicants managed to achieve this. On the other hand, 22 applicants named fewer than eight different judicial assessors and ten named fewer than six although they provided a satisfactory explanation for that. The report does not say who they were in terms of gender or the correlation between numbers of assessors and who was asked to interview and then recommended for appointment.

One needs to know if women applicants did find the new system (there were other changes as well) more suitable to their practices. We already know that at least in this year it did not lead to an increase in women applicants. All assessors were asked to rate the applicant in respect of each of the required competencies. 97% of clients rated the candidate very good or excellent but only 82% of judges did so and 84% of fellow practitioners.

After the papers sift, 181 applicants or 70% (but 81% of the women applicants) were invited to interview. Of those 63% were selected. As in the past, the more successful were the first-timers: 50% versus 35% of those who had applied in at least one of the last three competitions. 31% of returnees were not invited for interview regardless of whether they had been in the past.

QCA maintains diversity statistics, in addition to those relating to gender and ethnicity cited above. Eight applicants identified themselves as gay; six were recommended for appointment. Ten declared a disability; three were appointed. Youth prevailed: 57% of the 21 applicants under the age of 40 who applied were recommended but only 29% of the 89 aged 51 and over.

There is no attempt to obtain information regarding applicants’ education or their socio-economic background despite QCA’s traditional assurance that the rank of QC is not confined to those who attended Oxford or Cambridge let alone a fee-paying school. Barristers in civil chambers are more forthcoming about their education as part of their profile on the chambers website than those doing publicly funded work. Of the 71 civil QCs, 51 give their universities. Of these 31 are Oxford or Cambridge and 18 are other Russell Group universities. Of the 11 family QCs, five give their universities – two Oxbridge, three other Russell Group. Of the 25 criminal QCs, ten give their universities – three Oxford, and seven other Russell Group universities.

The QCA report concludes: ‘The agreed process was designed to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointment with the assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants. We remain concerned that the level of applications from solicitor advocates remains comparatively low.’ Once again, QCA undertakes to liaise with the Solicitors’ Association of Higher Courts Advocates and the Law Society to explore what can be done ‘to overcome this problem’. Nine solicitors applied this year, seven were interviewed and four were recommended for appointment. They, like one of the two employed barristers (the other is a woman and a CPS Crown Advocate), are partners in ‘magic circle’ solicitors’ firms operating out of Paris or Hong Kong, and engaged in international arbitration, which at the Bar would be labelled ‘niche’.

Does the list say anything about the health of the Bar? Is the number of cases requiring a QC and/or more than one counsel increasing or shrinking? Overall, the numbers of new QCs is buoyant and much higher than it was until a few years ago. The criminal Bar’s new QC numbers dipped to 17 in 2015-16 but then rose to 38, 40 and 39 in the next three competitions. This time it was down to 26. The number of family silks, which had averaged 7.5, atrophied to six and then four last year but this time was up to 11 (plus two with combined practices). The majority of these specialised in children matters. The civil Bar – which includes a very wide range of work – resumed its dominant position, with 71 or 62% of the total.

The Panel sees no diminution in quality. Whoever the non-applicants are, amongst those who do apply, QCA is spoiled for choice.

The statistics in this article were updated on 7 February 2020.

Elizabeth Gardiner CB; Lynda Gibbs; Millicent Grant; Professor Eva Lomnicka; Glyn Maddocks; Professor Judith Masson; Professor Clare McGlynn; Rodger Pannone; Professor Jane Stapleton; Daniel Winterfeldt

Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Barnard | Jonathan James |

| Mr | Brady | Michael Antony |

| Ms | Brown | Cameron Kennedy Duncan |

| Mr | Clare | Allison Jean |

| Mr | Cooper | Ben Lion |

| Mr | de la Poer | Nicholas John |

| Mr | Ford | Mark Steven |

| Mr | Garcha | Gurdeep Singh |

| Mr | Graffius | Mark Narayan |

| Mr | Hipkin | John Leslie |

| Mr | Hossain | Syed Ahmed Izharul |

| Miss | Hussain | Frida |

| Mr | Kazakos | Leon Samuel |

| Miss | Knight | Jennifer Claudia |

| Mr | Langdale | Adrian Mark |

| Mr | Mohindru | Anurag |

| Miss | Newell | Charlotte Anne |

| Miss | Osborne | Jane Elizabeth |

| Mr | Raudnitz | Paul Nikolai |

| Mr | Reiz | Stanley |

| Mr | Sandiford | Jonathan |

| Ms | Simpson | Melanie Denise |

| Miss | Stonecliffe | Heidi Lorraine |

| Mr | Storrie | Timothy James |

| Ms | Summers | Allison |

| Mr | Wood | Stephen |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Miss | Bowcock | Samantha Jane |

| Mrs | Carew Pole | Rebecca Jane |

| Miss | Hillas | Samantha |

| Mr | Kingerley | Martin Goddard |

| Ms | Mills | Barbara |

| Mr | Mitchell | Peter |

| Mr | Oliver | Harry John William |

| Ms | Perry | Cleo |

| Mr | Roche | Brendan |

| Mr | Sampson | Jonathan Robert |

| Mr | Webster | Simon Mark |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Adamson | Dominic James |

| Mr | Barclay | Robin Nicholas John |

| Mr | Butt | Matthew Paul |

| Mr | Hodivala | Jamas Rusi |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Mr | Allen | William Andrew |

| Mr | Atkins | Siward |

| Ms | Barton | Zoë Maria Marsden |

| Mr | Blackaby | Nigel Alexander |

| Mr | Blundell | David Anthony |

| Mr | Boardman | Christopher Leigh Wilson |

| Mr | Buckingham | Stewart John |

| Mr | Byam-Cook | Henry James |

| Miss | Carpenter | Chloe |

| Mr | Carpenter | James Frederick Horatio |

| Mr | Chapman | Simon James |

| Mr | Collingwood | Timothy Donald |

| Mr | Cowen | Gary Adam |

| Mr | Dignum | Marcus Benedict |

| Mr | Doyle | Louis George |

| Mr | Duncan | Delroy Benell |

| Mr | Fisher | Richard Mark |

| Mr | Fry | Jason Alva |

| Mr | Goatley | Peter Seamus Patrick |

| Mr | Goldsmith | James Daniel |

| Mr | Grantham | Andrew Timothy |

| Mr | Hall Taylor | Alexander Edward |

| Mr | Higgo | Justin Beresford |

| Ms | Jhangiani | Sapna |

| Ms | Leahy | Blair Patricia |

| Miss | Lee | Krista |

| Mr | Levey | Edward Michael |

| Mr | Liddell | Richard Ian |

| Mr | Lynch | Benjamin John Patrick |

| Mr | Lyness | Scott Edward |

| Mr | Majumdar | Shantanu Joseph |

| Mr | Mallalieu | Roger |

| Ms | McColgan | Aileen |

| Mr | McDougall | Andrew de Lotbinière |

| Professor | McMeel | Gerard Patrick |

| Mr | Mehrzad | John |

| Mr | Milford | Julian Robert |

| Ms | Mitrophanous | Eleni |

| Mr | Mold | Andrew Matthew Stephen |

| Ms | Newton | Katharine Julia |

| Mr | Norris | Andrew James Steedsman |

| Ms | Omambala | Ijeoma Chinyelu |

| Ms | Oppenheimer | Tamara Helen Pasternak |

| Mr | Panesar | Deshpal |

| Mr | Patton | Conall |

| Mr | Pickering | James Patrick |

| Mr | Pievsky | David Richard |

| Mr | Pilgerstorfer | Marcus James |

| Mr | Pillai | Rajesh |

| Mr | Pitchers | Henry William Stodart |

| Ms | Plowden | Sarah Selena Rixar |

| Mr | Riches | Philip Geoffrey Hurry |

| Mr | Richmond | Jeremy John |

| Mr | Rosenthal | Adam Julius |

| Mr | Rubins | Noah Daniel |

| Mr | Salve | Harish |

| Ms | Savage | Amanda Claire |

| Dr | Scannell | David Luke |

| Mr | Segan | James Jeffrey |

| Miss | Selway | Katherine Emma |

| Mr | Shivji | Sharif Asim |

| Mr | Simblet | Stephen John |

| Mr | Speker | Adam |

| Miss | Thomas | Jacqueline Louise |

| Mr | Thornton | Andrew James |

| Ms | Tuck | Rebecca Louise |

| Mr | Wald | Richard Daniel |

| Mr | Warwick | Henry |

| Mr | West | Colin |

| Mr | Wheeler | Giles Neil Laurence |

| Mr | Williams | Robert Brychan James |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Ms | Carter-Manning | Jennifer Anne |

| Title | Surname | Forenames |

| Miss | Munroe | Veronica Allison |

Celebrating the 114 new silks – plus forensic analysis of the 2019 cohort and what it says about equality of opportunity in the profession and health of the Bar –by David Wurtzel

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier