*/

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

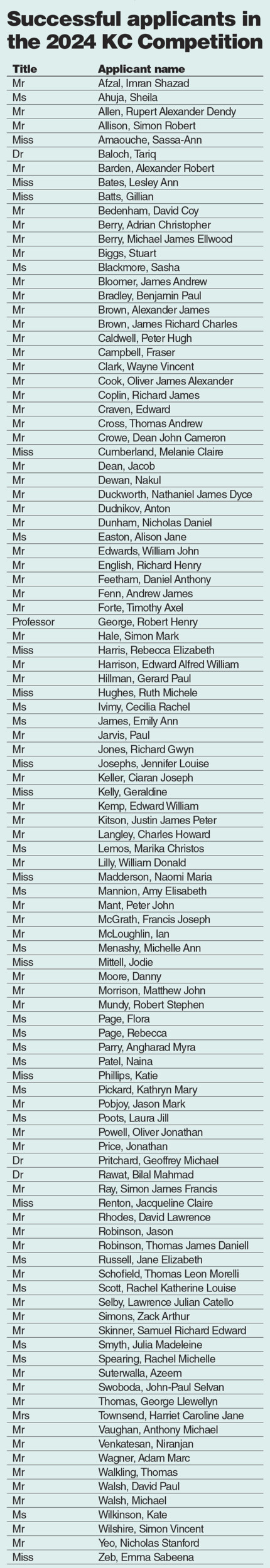

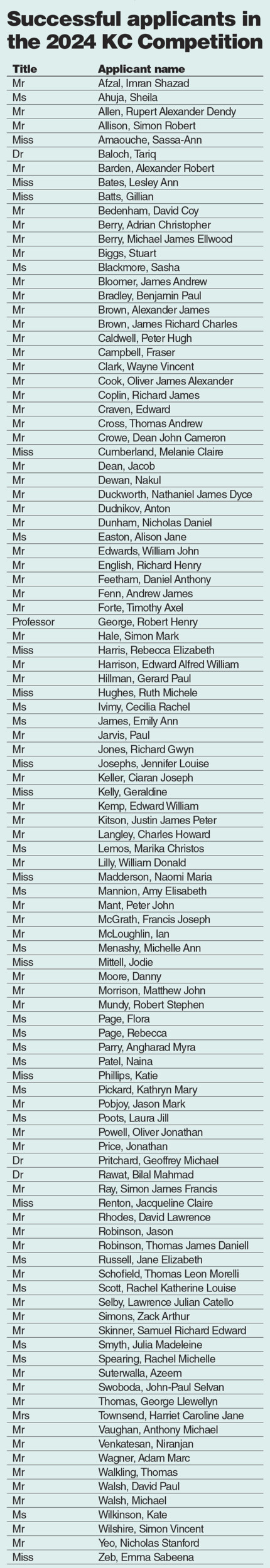

‘The Panel needs to see strong and consistent evidence of excellence, not merely evidence of a high degree of competence, in order to recommend appointment.’ Thus the King’s Counsel Selection Panel (‘the panel’) sets out its traditional approach to the 2024 competition. The list of successful applicants was published on 24 January 2025. Further and minute detail can be found in the panel’s Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Process for the Selection of King’s Counsel (20 pages) and the Panel Approach to Competencies (ten pages).

All unsuccessful candidates receive a feedback letter and thus know why they have not been selected. All applicants should be interviewed unless ‘it is clear having considered the assessments from the assessors together with the applicant’s own self-assessment that they have no reasonable prospect of success’. This is a decision of the entire panel, taken at the pre-interview moderation meeting. This year, 54% of applicants fell into that category. Those who were interviewed but not recommended also receive feedback, setting out what conclusion was reached in respect of each of the competencies. This is also a decision of the entire panel at final moderation, not just the interviewing pair. If anyone wishes to explore further, in particular in respect of any group, then the starting point is to analyse those feedback letters, and to see whether they disclose anything more than an assessment of that particular individual.

Applying for silk is a process which only concerns a tiny number of barristers who are well into their careers and are not by definition representative of the Bar. The number of applicants in 2024 was 327, the highest figure since 2007-8 when it was 333. There were 105 successful applicants, which happens to be the average number over the previous 17 years. However, look at percentages and something significant is clear. The percentage of success has been dropping, year on year, while the percentage of those who are weeded out before interview has been rising, year on year. In 2019, 44% of all applicants were successful. That declined to 41% in 2020, 37% in 2021, 34% in 2022 and 33.5% in 2023. This year it was 32%, the lowest since 2007-8. Meanwhile, the number of those invited for interview is falling. It was 63% in 2020 but only 46% this year. There is no lack of practice in applying: 40% of applicants this year (134) had applied at least once in the previous three years. Of those, 74 or 55% fell at the first hurdle although 20 of them had been interviewed in the past. First-time applicants had a similar early failure rate. Both seasoned and new applicants had the same overall outcome for success: 33% for repeat applicants, 32% for new ones.

No one applies casually. The application fee is now £2,100.* Successful candidates in addition pay an appointment fee of £3,600 plus the cost of Letters Patent. Then there are the new robes – and perhaps a party to celebrate. A huge amount of time is spent by applicants on the application itself, as last year’s feedback showed. They must also put forward assessors. Ideally, that means 12 judicial, 12 practitioner and six client assessors. This year, 49% of applicants met that ideal. Assuming for a moment that they included all of the 32% who were successful, a third of that 49% failed regardless. Some would not have been interviewed, since the panel would have concluded that on the basis of those assessments they had no reasonable chance of success.

This year as before, success goes to the young and precocious. There were 32 applicants aged 40 and under, of whom 21 (66%) were interviewed and 18 (56% of the total and 85% of those interviewed) were appointed. There were 150 aged 50 and over. Only 49 (38%) were interviewed and 32 (25% of the total and 65% of those interviewed) were appointed. This leaves 145 aged 41-49 who provided the remaining 55 successful applicants or a 38% success rate.

In addition to the small number of applicants who apply for silk, the process is traditionally relevant only to a small number of chambers. There are over 400 chambers with more than one practising barrister. This year, 70 chambers provided the 104 successful barristers. The average for the previous four years is 65. Although year on year chambers come in and out of the list, there are some which appear almost every year: Doughty Street, Essex Street (each of whom produced five new KCs this year), 23 Essex Street, 6 KBW College Hill and Landmark (who had four each), One Essex Court, Brick Court, Blackstone, 1 Garden Court, Garden Court, St Phillips and 36 Group to name only some. This year, six sets produced half the new criminal KCs, and 12 sets produced half the number of new civil KCs.

The process remains London-centric. Twenty out of 24 sets which produced practitioners in crime or crime and civil, six out of seven sets of family practitioners and 38 out of 39 sets of civil practitioners are London-based.

Yet again, every new silk is in chambers that already has silks. The mentors are in-house. The number of existing silks in civil sets varies from six to 62. The average is 25. For family practitioners the average is ten. For criminal practitioners it is 15. Some years there are one or two ‘first in chambers’ silks, but not every year and no more than one or two. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that however hard any barrister works, developing a pre-silk practice is also a function of opportunity and those opportunities are likely to be found in no more than a quarter of all the sets at the Bar.

A process which is designed to identify excellence in advocacy is relevant primarily to the self-employed Bar. Each year, the Report to the Lord Chancellor notes that the process was designed ‘to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointment with assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants’. Each year, the Report notes the dearth of solicitor applicants and of successful ones. Each year, the Report gives an assurance that the panel is working with the Law Society to encourage more applicants. Nothing changes. Over the past 17 years the average number of solicitor applicants is 7.7; the average number of those recommended for appointment is three. For the third successive year there is only one new solicitor KC. She is a partner in A&O Shearman and specialises in international commercial arbitration.

Employed barristers fare worse. The average number of applicants over the previous 17 years is 4.8. The average recommended for appointment is one. This year there were five applicants, none of whom was interviewed. The reason can be found on the website: the award of King’s Counsel is made ‘for excellence in advocacy in the higher courts’. Candidates are thus required to list 12 cases of substance and for each case to name a judicial and a practitioner assessor plus at least six client assessors. If their work is not as an advocate in the higher courts and they are not in a position to list a suitable number of such assessors, then they do not qualify for an award.

The panel does not operate quotas of any kind. However, the distribution of work among those recommended tends to be similar, year on year. Presumably this reflects the areas of work where silks are needed. This year, 63 people or 60% of the successful cohort does civil work. Last year it was 58 or 61%. It was 63 the year before that. Both this year and last year, 25 gave crime as their area of practice. The family Bar produces the smallest number of new silks. The average since 2014 is 7.4. This year it is eight.

Civil work includes a very broad range of work and specialisms. It is also where the precocious young are to be found. Of the 62 civil barristers, 13 or 21% were called in 2000 or before; 42 or 67% between 2001-8 and seven since 2009. The latter includes the youngest in the whole cohort, who was called in 2015. Family law divides almost equally between those called in the 1990s and those called from 2000 to 2007, with one called in 2013. In terms of work, seven specialise in matters relating to children and one in financial matters. Crime divides between half called before 2000 and half called between 2000-7.

Each area of practice reflects a different educational background. Not all barristers list their education or prizes on the chambers website. It is more common among civil practitioners. Of the 62 civil self-employed barristers, at least 40 went to Oxford and/or Cambridge. That includes four top Firsts in their year and three double firsts. In addition 20 others note their first class degrees. At least 12 others went to Russell Group universities. None of this is disclosed to the panel, but if one wants to know who gets into silk-heavy chambers, it does help to answer the question ‘Who gets pupillage and where’ and what that means to a career. Among the eight family practitioners, three went to Oxford or Cambridge and four to Russell Group universities. Criminal practitioners are least likely to cite education on the website. At least two went to Oxford or Cambridge and ten to Russell Group universities.

Although the diversity information is dealt with in the Report characteristic by characteristic, there is no information on the extent to which one or more applies to any individual candidate and how much overlap there may have been.

In terms of gender, for many years the number of women applicants hovered around 40 per year. This rose to the 50s from 2018 and the 70s from 2020. This year it was a record 85 though not an increase (26%) in percentage terms. Women in the great majority of years have a higher success rate than men and they did so again this year (39% vs 30%). However, this is also a year of an overall low success rate. Only 33 were recommended for appointment. This is higher than last year’s 30 but below the average of 40 in the three years before that. As for raw numbers, six out of eight in family work are women, ten out of 34 in crime and crime/civil (70/30%) and 17 out of 63 (73/27%) in civil.

In line with the higher number of applicants, there were 60 who declared an ethnic origin other than White – the average in the previous seven years was 38 although it was 48 last year. Only 23 were interviewed – 38% as opposed to 48% for White applicants – but 18 were recommended, which is 78% of those interviewed. In total 30% of those who declared an ethnic origin were recommended, as opposed to 33% of White applicants. This is a rise over last year (27%) but well below the average of 41% in the ten years before that. There were seven Asian or Asian British successful applicants, all of whom appear to be in the civil cohort, out of 29 applicants and ten out of 17 of those who declared a mixed or multiple ethnic groups. There was one ‘other’. None of the ten Black, African, Caribbean or Black British applicants were successful. Sixteen in total have been recommended in the previous seven years.

There were 14 applicants who identified as a gay man or woman. Eight or 57% were invited to interview and six or 43% were recommended together with one bisexual applicant. This, as usual, exceeded the success rate for the whole cohort. Nineteen applicants declared a disability. Eleven (58%) were interviewed and eight recommended for appointment (42% overall success and 72% of those who were interviewed).

Applying for silk is a major challenge. It is a personal and professional decision for each individual as to whether it is right for them. That does not deter a rising number of barristers from applying. What needs to be realised is how daunting it is to succeed.

* Reduced application fee: In 2017, the professional bodies introduced a facility for reduced fees (payable at half the standard amounts) for applicants with low earnings, defined as below £90,000 in fees for those at the self-employed Bar. Eight applicants took advantage of the reduced fee in 2024.

Don’t miss the COUNSEL Silk Supplement 2025: Chambers celebrate their new silks and, for those weighing up the next competition, recent silks share their advice on how to approach the form – and your assessors – as well as setting up a new silk practice. Hear from Maryam Syed KC, Deshpal Panesar KC, Anita Guha KC, Susannah Johnson KC and Jeffrey Jupp KC. Plus, insight from Sir Paul Morgan of the KC Selection Panel, coach Paul Secher and Mike Jones KC on applying for silk from the employed Bar. Now online here.

Joint ICAW panel discussion with King’s Counsel Appointments looking at the process of applying for silk. Open to all (in-person tickets are £10; £5 online). Book your place here.

‘The Panel needs to see strong and consistent evidence of excellence, not merely evidence of a high degree of competence, in order to recommend appointment.’ Thus the King’s Counsel Selection Panel (‘the panel’) sets out its traditional approach to the 2024 competition. The list of successful applicants was published on 24 January 2025. Further and minute detail can be found in the panel’s Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Process for the Selection of King’s Counsel (20 pages) and the Panel Approach to Competencies (ten pages).

All unsuccessful candidates receive a feedback letter and thus know why they have not been selected. All applicants should be interviewed unless ‘it is clear having considered the assessments from the assessors together with the applicant’s own self-assessment that they have no reasonable prospect of success’. This is a decision of the entire panel, taken at the pre-interview moderation meeting. This year, 54% of applicants fell into that category. Those who were interviewed but not recommended also receive feedback, setting out what conclusion was reached in respect of each of the competencies. This is also a decision of the entire panel at final moderation, not just the interviewing pair. If anyone wishes to explore further, in particular in respect of any group, then the starting point is to analyse those feedback letters, and to see whether they disclose anything more than an assessment of that particular individual.

Applying for silk is a process which only concerns a tiny number of barristers who are well into their careers and are not by definition representative of the Bar. The number of applicants in 2024 was 327, the highest figure since 2007-8 when it was 333. There were 105 successful applicants, which happens to be the average number over the previous 17 years. However, look at percentages and something significant is clear. The percentage of success has been dropping, year on year, while the percentage of those who are weeded out before interview has been rising, year on year. In 2019, 44% of all applicants were successful. That declined to 41% in 2020, 37% in 2021, 34% in 2022 and 33.5% in 2023. This year it was 32%, the lowest since 2007-8. Meanwhile, the number of those invited for interview is falling. It was 63% in 2020 but only 46% this year. There is no lack of practice in applying: 40% of applicants this year (134) had applied at least once in the previous three years. Of those, 74 or 55% fell at the first hurdle although 20 of them had been interviewed in the past. First-time applicants had a similar early failure rate. Both seasoned and new applicants had the same overall outcome for success: 33% for repeat applicants, 32% for new ones.

No one applies casually. The application fee is now £2,100.* Successful candidates in addition pay an appointment fee of £3,600 plus the cost of Letters Patent. Then there are the new robes – and perhaps a party to celebrate. A huge amount of time is spent by applicants on the application itself, as last year’s feedback showed. They must also put forward assessors. Ideally, that means 12 judicial, 12 practitioner and six client assessors. This year, 49% of applicants met that ideal. Assuming for a moment that they included all of the 32% who were successful, a third of that 49% failed regardless. Some would not have been interviewed, since the panel would have concluded that on the basis of those assessments they had no reasonable chance of success.

This year as before, success goes to the young and precocious. There were 32 applicants aged 40 and under, of whom 21 (66%) were interviewed and 18 (56% of the total and 85% of those interviewed) were appointed. There were 150 aged 50 and over. Only 49 (38%) were interviewed and 32 (25% of the total and 65% of those interviewed) were appointed. This leaves 145 aged 41-49 who provided the remaining 55 successful applicants or a 38% success rate.

In addition to the small number of applicants who apply for silk, the process is traditionally relevant only to a small number of chambers. There are over 400 chambers with more than one practising barrister. This year, 70 chambers provided the 104 successful barristers. The average for the previous four years is 65. Although year on year chambers come in and out of the list, there are some which appear almost every year: Doughty Street, Essex Street (each of whom produced five new KCs this year), 23 Essex Street, 6 KBW College Hill and Landmark (who had four each), One Essex Court, Brick Court, Blackstone, 1 Garden Court, Garden Court, St Phillips and 36 Group to name only some. This year, six sets produced half the new criminal KCs, and 12 sets produced half the number of new civil KCs.

The process remains London-centric. Twenty out of 24 sets which produced practitioners in crime or crime and civil, six out of seven sets of family practitioners and 38 out of 39 sets of civil practitioners are London-based.

Yet again, every new silk is in chambers that already has silks. The mentors are in-house. The number of existing silks in civil sets varies from six to 62. The average is 25. For family practitioners the average is ten. For criminal practitioners it is 15. Some years there are one or two ‘first in chambers’ silks, but not every year and no more than one or two. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that however hard any barrister works, developing a pre-silk practice is also a function of opportunity and those opportunities are likely to be found in no more than a quarter of all the sets at the Bar.

A process which is designed to identify excellence in advocacy is relevant primarily to the self-employed Bar. Each year, the Report to the Lord Chancellor notes that the process was designed ‘to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointment with assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants’. Each year, the Report notes the dearth of solicitor applicants and of successful ones. Each year, the Report gives an assurance that the panel is working with the Law Society to encourage more applicants. Nothing changes. Over the past 17 years the average number of solicitor applicants is 7.7; the average number of those recommended for appointment is three. For the third successive year there is only one new solicitor KC. She is a partner in A&O Shearman and specialises in international commercial arbitration.

Employed barristers fare worse. The average number of applicants over the previous 17 years is 4.8. The average recommended for appointment is one. This year there were five applicants, none of whom was interviewed. The reason can be found on the website: the award of King’s Counsel is made ‘for excellence in advocacy in the higher courts’. Candidates are thus required to list 12 cases of substance and for each case to name a judicial and a practitioner assessor plus at least six client assessors. If their work is not as an advocate in the higher courts and they are not in a position to list a suitable number of such assessors, then they do not qualify for an award.

The panel does not operate quotas of any kind. However, the distribution of work among those recommended tends to be similar, year on year. Presumably this reflects the areas of work where silks are needed. This year, 63 people or 60% of the successful cohort does civil work. Last year it was 58 or 61%. It was 63 the year before that. Both this year and last year, 25 gave crime as their area of practice. The family Bar produces the smallest number of new silks. The average since 2014 is 7.4. This year it is eight.

Civil work includes a very broad range of work and specialisms. It is also where the precocious young are to be found. Of the 62 civil barristers, 13 or 21% were called in 2000 or before; 42 or 67% between 2001-8 and seven since 2009. The latter includes the youngest in the whole cohort, who was called in 2015. Family law divides almost equally between those called in the 1990s and those called from 2000 to 2007, with one called in 2013. In terms of work, seven specialise in matters relating to children and one in financial matters. Crime divides between half called before 2000 and half called between 2000-7.

Each area of practice reflects a different educational background. Not all barristers list their education or prizes on the chambers website. It is more common among civil practitioners. Of the 62 civil self-employed barristers, at least 40 went to Oxford and/or Cambridge. That includes four top Firsts in their year and three double firsts. In addition 20 others note their first class degrees. At least 12 others went to Russell Group universities. None of this is disclosed to the panel, but if one wants to know who gets into silk-heavy chambers, it does help to answer the question ‘Who gets pupillage and where’ and what that means to a career. Among the eight family practitioners, three went to Oxford or Cambridge and four to Russell Group universities. Criminal practitioners are least likely to cite education on the website. At least two went to Oxford or Cambridge and ten to Russell Group universities.

Although the diversity information is dealt with in the Report characteristic by characteristic, there is no information on the extent to which one or more applies to any individual candidate and how much overlap there may have been.

In terms of gender, for many years the number of women applicants hovered around 40 per year. This rose to the 50s from 2018 and the 70s from 2020. This year it was a record 85 though not an increase (26%) in percentage terms. Women in the great majority of years have a higher success rate than men and they did so again this year (39% vs 30%). However, this is also a year of an overall low success rate. Only 33 were recommended for appointment. This is higher than last year’s 30 but below the average of 40 in the three years before that. As for raw numbers, six out of eight in family work are women, ten out of 34 in crime and crime/civil (70/30%) and 17 out of 63 (73/27%) in civil.

In line with the higher number of applicants, there were 60 who declared an ethnic origin other than White – the average in the previous seven years was 38 although it was 48 last year. Only 23 were interviewed – 38% as opposed to 48% for White applicants – but 18 were recommended, which is 78% of those interviewed. In total 30% of those who declared an ethnic origin were recommended, as opposed to 33% of White applicants. This is a rise over last year (27%) but well below the average of 41% in the ten years before that. There were seven Asian or Asian British successful applicants, all of whom appear to be in the civil cohort, out of 29 applicants and ten out of 17 of those who declared a mixed or multiple ethnic groups. There was one ‘other’. None of the ten Black, African, Caribbean or Black British applicants were successful. Sixteen in total have been recommended in the previous seven years.

There were 14 applicants who identified as a gay man or woman. Eight or 57% were invited to interview and six or 43% were recommended together with one bisexual applicant. This, as usual, exceeded the success rate for the whole cohort. Nineteen applicants declared a disability. Eleven (58%) were interviewed and eight recommended for appointment (42% overall success and 72% of those who were interviewed).

Applying for silk is a major challenge. It is a personal and professional decision for each individual as to whether it is right for them. That does not deter a rising number of barristers from applying. What needs to be realised is how daunting it is to succeed.

* Reduced application fee: In 2017, the professional bodies introduced a facility for reduced fees (payable at half the standard amounts) for applicants with low earnings, defined as below £90,000 in fees for those at the self-employed Bar. Eight applicants took advantage of the reduced fee in 2024.

Don’t miss the COUNSEL Silk Supplement 2025: Chambers celebrate their new silks and, for those weighing up the next competition, recent silks share their advice on how to approach the form – and your assessors – as well as setting up a new silk practice. Hear from Maryam Syed KC, Deshpal Panesar KC, Anita Guha KC, Susannah Johnson KC and Jeffrey Jupp KC. Plus, insight from Sir Paul Morgan of the KC Selection Panel, coach Paul Secher and Mike Jones KC on applying for silk from the employed Bar. Now online here.

Joint ICAW panel discussion with King’s Counsel Appointments looking at the process of applying for silk. Open to all (in-person tickets are £10; £5 online). Book your place here.

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Now is the time to tackle inappropriate behaviour at the Bar as well as extend our reach and collaboration with organisations and individuals at home and abroad

A comparison – Dan Monaghan, Head of DWF Chambers, invites two viewpoints

And if not, why not? asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Head of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, discusses the many benefits of oral fluid drug testing for child welfare and protection matters

To mark International Women’s Day, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management looks at how financial planning can help bridge the gap

Casey Randall of AlphaBiolabs answers some of the most common questions regarding relationship DNA testing for court

Maria Scotland and Niamh Wilkie report from the Bar Council’s 2024 visit to the United Arab Emirates exploring practice development opportunities for the England and Wales family Bar

Marking Neurodiversity Week 2025, an anonymous barrister shares the revelations and emotions from a mid-career diagnosis with a view to encouraging others to find out more

David Wurtzel analyses the outcome of the 2024 silk competition and how it compares with previous years, revealing some striking trends and home truths for the profession

Save for some high-flyers and those who can become commercial arbitrators, it is generally a question of all or nothing but that does not mean moving from hero to zero, says Andrew Hillier